Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Issue Briefs

Data Bulletins

Research Briefs

Policy Analyses

Community Reports

Journal Articles

Other Publications

Surveys

Site Visits

Design and Methods

Data Files

|

Financial Pressures Continue to Plague Hospitals

Northern New Jersey

Community Report No. 12

Summer 2001

Debra A. Draper, Linda R. Brewster, Lawrence D. Brown, Lance Heineccius, Carolyn A. Watts, Elizabeth Eagan, Leslie A. Jackson, Marie C. Reed

n March 2001, a team of researchers

visited northern New Jersey to study

that community’s health system, how

it is changing and the effects of those

changes on consumers. The Center for

Studying Health System Change

(HSC), as part of the Community

Tracking Study, interviewed more

than 60 leaders in the health care

market. Northern New Jersey is one of

12 communities tracked by HSC

every two years through site visits and

surveys. Individual community reports

are published for each round of site

visits. The first two site visits to

northern New Jersey, in 1997 and

1999, provided baseline and initial

trend information against which

changes are tracked. The northern

New Jersey market encompasses

Essex, Morris, Sussex, Union and

Warren counties. n March 2001, a team of researchers

visited northern New Jersey to study

that community’s health system, how

it is changing and the effects of those

changes on consumers. The Center for

Studying Health System Change

(HSC), as part of the Community

Tracking Study, interviewed more

than 60 leaders in the health care

market. Northern New Jersey is one of

12 communities tracked by HSC

every two years through site visits and

surveys. Individual community reports

are published for each round of site

visits. The first two site visits to

northern New Jersey, in 1997 and

1999, provided baseline and initial

trend information against which

changes are tracked. The northern

New Jersey market encompasses

Essex, Morris, Sussex, Union and

Warren counties.

Since 1999, when hospitals and health plans in northern

New Jersey were struggling with poor financial performance,

many hospitals’ financial problems have worsened.

The state hospital association reports that 60 percent of

New Jersey’s hospitals currently operate in the red. Small

and urban safety net hospitals appear to be the most

severely affected, raising concerns about low-income and

uninsured residents’ continued access to care. In contrast,

most health plans are now financially stable and reporting

profits. Meanwhile, many employers have experienced

double-digit premium increases, and some enrollees

face reduced options as plans become choosier about

their customers and turn down some employers.

Other important developments since 1999 include:

- Health plans shed unprofitable lines of business and

experimented with utilization management strategies

to improve profitability.

- The New Jersey Legislature debated new managed care

laws and added to extensive laws governing health

plans already on the books.

- Public insurance coverage expanded, but key safety net

providers remain on shaky ground.

Urban Hospitals’ Fiscal Health

Remains Critical

orthern New Jersey has long been noted

for its excess hospital bed capacity and

high utilization of services-both of

which have contributed to higher than

average health care costs. The market’s

inpatient capacity is 36 percent higher

than that of the average metropolitan

market, and its Medicare patients’ hospital

length of stay exceeds the national

average by 50 percent. In the early 1990s,

state policy makers sought to address

these problems by deregulation, replacing

the hospital rate-setting system with a

competitive model to drive down costs.

Since then, hospitals in northern New

Jersey have struggled financially, and significant

efficiencies have not materialized.

In the past two years, hospitals in

the market have continued to be plagued

by financial pressures that stem from

continued low payment rates and rising

operating costs, due in part to a nursing

shortage. In addition, hospitals have seen

their revenues diminish because health

plans have become more aggressive in

their inpatient utilization management

efforts-for example, by significantly

increasing the number of denied days

(days of a hospital stay for which health

plans refuse to pay) and downgraded days

(days reimbursed at a lower rate than usual).

Northern New Jersey’s urban hospitals

are in far worse financial condition

than its suburban-based hospitals, and the

financial gap continues to widen. Urban

hospitals-which constitute the core safety

net for low-income, uninsured individuals-

have been particularly hard hit by

declining patient volume and fewer privately

insured patients. Although many

urban facilities have been financially distressed

for some time, the cumulative

effect of these pressures has heightened

concerns about their viability and implications

for low-income, uninsured patients’

access to care.

Such concerns contributed to a

recent decision to allocate state funds

totaling $9.5 million in 2001 and $5 million

in 2002 to Cathedral Healthcare

System, a Catholic hospital system with

two key safety net facilities in downtown

Newark that were in declining financial

health and threatening to scale back services.

The state also increased its $320

million charity care pool by $36 million

this year-and expects to add $25 million

more in 2002-to assist hospitals serving

the uninsured. Nonetheless, hospital leaders

lament that current state funding for

charity care remains well below the $700

million available before deregulation.

Meanwhile, the finances of northern

New Jersey’s two largest, predominantly

suburban-based hospital systems-St.

Barnabas Health Care System and Atlantic

Health System-are improving. Both systems

were formed in the mid-1990s and,

by 2000, both reported profits, recovering

from previous years’ losses. Their strong

suburban base gives them a more diverse

payer mix, with a higher proportion of

privately insured patients who supply a

steady source of revenue, than their urban

counterparts. Although the suburban

hospital systems have not escaped labor

costs and problems with denied and

downgraded days, they have benefited

from various cost-cutting measures.

In addition, the nine-hospital St.

Barnabas system and four-hospital

Atlantic system have been aggressively

leveraging their size and reputation in

contract negotiations with plans in the

past two years and succeeded in winning

higher payments. Both systems have established

themselves as "must-have" providers

that purchasers insist are included in plan

networks. They also have gained significant

negotiating leverage with plans by moving

to system-wide contracts instead of individually

negotiated contracts for each

affiliated hospital.

Last year, conflict over payment rates

and issues such as utilization management

led to a highly publicized contract dispute

between Atlantic and Aetna U.S. Healthcare.

Both parties made concessions, and new

contract terms were eventually negotiated.

Aetna is reportedly paying significantly

higher rates to Atlantic; Atlantic, in turn,

reportedly signed a multiyear contract,

which helped ensure the stability of

Aetna’s network. orthern New Jersey has long been noted

for its excess hospital bed capacity and

high utilization of services-both of

which have contributed to higher than

average health care costs. The market’s

inpatient capacity is 36 percent higher

than that of the average metropolitan

market, and its Medicare patients’ hospital

length of stay exceeds the national

average by 50 percent. In the early 1990s,

state policy makers sought to address

these problems by deregulation, replacing

the hospital rate-setting system with a

competitive model to drive down costs.

Since then, hospitals in northern New

Jersey have struggled financially, and significant

efficiencies have not materialized.

In the past two years, hospitals in

the market have continued to be plagued

by financial pressures that stem from

continued low payment rates and rising

operating costs, due in part to a nursing

shortage. In addition, hospitals have seen

their revenues diminish because health

plans have become more aggressive in

their inpatient utilization management

efforts-for example, by significantly

increasing the number of denied days

(days of a hospital stay for which health

plans refuse to pay) and downgraded days

(days reimbursed at a lower rate than usual).

Northern New Jersey’s urban hospitals

are in far worse financial condition

than its suburban-based hospitals, and the

financial gap continues to widen. Urban

hospitals-which constitute the core safety

net for low-income, uninsured individuals-

have been particularly hard hit by

declining patient volume and fewer privately

insured patients. Although many

urban facilities have been financially distressed

for some time, the cumulative

effect of these pressures has heightened

concerns about their viability and implications

for low-income, uninsured patients’

access to care.

Such concerns contributed to a

recent decision to allocate state funds

totaling $9.5 million in 2001 and $5 million

in 2002 to Cathedral Healthcare

System, a Catholic hospital system with

two key safety net facilities in downtown

Newark that were in declining financial

health and threatening to scale back services.

The state also increased its $320

million charity care pool by $36 million

this year-and expects to add $25 million

more in 2002-to assist hospitals serving

the uninsured. Nonetheless, hospital leaders

lament that current state funding for

charity care remains well below the $700

million available before deregulation.

Meanwhile, the finances of northern

New Jersey’s two largest, predominantly

suburban-based hospital systems-St.

Barnabas Health Care System and Atlantic

Health System-are improving. Both systems

were formed in the mid-1990s and,

by 2000, both reported profits, recovering

from previous years’ losses. Their strong

suburban base gives them a more diverse

payer mix, with a higher proportion of

privately insured patients who supply a

steady source of revenue, than their urban

counterparts. Although the suburban

hospital systems have not escaped labor

costs and problems with denied and

downgraded days, they have benefited

from various cost-cutting measures.

In addition, the nine-hospital St.

Barnabas system and four-hospital

Atlantic system have been aggressively

leveraging their size and reputation in

contract negotiations with plans in the

past two years and succeeded in winning

higher payments. Both systems have established

themselves as "must-have" providers

that purchasers insist are included in plan

networks. They also have gained significant

negotiating leverage with plans by moving

to system-wide contracts instead of individually

negotiated contracts for each

affiliated hospital.

Last year, conflict over payment rates

and issues such as utilization management

led to a highly publicized contract dispute

between Atlantic and Aetna U.S. Healthcare.

Both parties made concessions, and new

contract terms were eventually negotiated.

Aetna is reportedly paying significantly

higher rates to Atlantic; Atlantic, in turn,

reportedly signed a multiyear contract,

which helped ensure the stability of

Aetna’s network.

Back to Top

Plans Move to Protect Profit,

Exiting Public Programs

ince 1999, health plans in northern New Jersey have taken

several measures to improve their profitability-including increasing premiums,

shedding unprofitable lines of business and implementing aggressive utilization

management strategies. While such measures have brought greater financial stability

to the plan market, they also have brought rising premiums and fewer options for

Medicare and Medicaid enrollees.

Many health plans have instituted

double-digit premium increases. Employers

in New Jersey’s still-tight labor market have

generally absorbed the premium hikes,

making only modest increases in deductibles

and copayments for employees. Many

plans and employers also have adopted

three-tier pharmacy benefit structures to

combat rapidly rising pharmaceutical costs.

Instead of trying to expand market

share, health plans have been taking a close

look at their portfolios and shedding

unprofitable accounts and lines of business.

As a result, several plans have decided to

abandon the Medicare and Medicaid markets.

Three plans stopped participating in

Medicare+Choice, and others reduced service

areas, citing low payment rates and

onerous program requirements. Currently,

90 percent of northern New Jersey’s 25,000

Medicare+Choice members are enrolled in

either Aetna or Horizon Blue Cross Blue

Shield of New Jersey, but some observers

believe that both plans may be considering

ending their participation in

Medicare+Choice.

Furthermore, Aetna recently

announced it is selling its Medicaid line

of business to AmeriChoice, the second

largest Medicaid plan in northern New

Jersey. As a result, Aetna’s 118,000 Medicaid

enrollees in New Jersey are expected to

move to AmeriChoice. These changes

may be blocked, however, because Aetna

is bound by a consent decree to participate

in Medicare and Medicaid until 2003,

according to the terms of the state’s approval

of Aetna’s recent acquisition of Prudential.

In the past two years, further growth

in health care utilization in northern New

Jersey-already a high-utilization market-

has been reported by health plans. Although

many plans have relaxed preauthorization

and referral requirements in response to

growing market demand for less restrictive

care, they also have implemented

other utilization management strategies

aggressively in an effort to rein in costs.

Many plans have adopted more stringent

utilization management criteria and are

adhering to these standards more strictly.

The result has been a growing number

of denied and downgraded days, which

has angered providers.

Some plans also have increased the

intensity of inpatient utilization management.

Last year, Aetna placed nurses on

site at several hospitals to assist with utilization

management, including discharge

planning, and plans to triple the number

of nurses involved in such utilization

management activities by the end of this

year. Other health plans similarly report

stepped-up activities focusing on discharge

planning. Some hospitals view

these activities as intrusive, but others

reportedly are receptive to having additional

personnel provide assistance,

particularly as hospitals struggle with

a nursing shortage. ince 1999, health plans in northern New Jersey have taken

several measures to improve their profitability-including increasing premiums,

shedding unprofitable lines of business and implementing aggressive utilization

management strategies. While such measures have brought greater financial stability

to the plan market, they also have brought rising premiums and fewer options for

Medicare and Medicaid enrollees.

Many health plans have instituted

double-digit premium increases. Employers

in New Jersey’s still-tight labor market have

generally absorbed the premium hikes,

making only modest increases in deductibles

and copayments for employees. Many

plans and employers also have adopted

three-tier pharmacy benefit structures to

combat rapidly rising pharmaceutical costs.

Instead of trying to expand market

share, health plans have been taking a close

look at their portfolios and shedding

unprofitable accounts and lines of business.

As a result, several plans have decided to

abandon the Medicare and Medicaid markets.

Three plans stopped participating in

Medicare+Choice, and others reduced service

areas, citing low payment rates and

onerous program requirements. Currently,

90 percent of northern New Jersey’s 25,000

Medicare+Choice members are enrolled in

either Aetna or Horizon Blue Cross Blue

Shield of New Jersey, but some observers

believe that both plans may be considering

ending their participation in

Medicare+Choice.

Furthermore, Aetna recently

announced it is selling its Medicaid line

of business to AmeriChoice, the second

largest Medicaid plan in northern New

Jersey. As a result, Aetna’s 118,000 Medicaid

enrollees in New Jersey are expected to

move to AmeriChoice. These changes

may be blocked, however, because Aetna

is bound by a consent decree to participate

in Medicare and Medicaid until 2003,

according to the terms of the state’s approval

of Aetna’s recent acquisition of Prudential.

In the past two years, further growth

in health care utilization in northern New

Jersey-already a high-utilization market-

has been reported by health plans. Although

many plans have relaxed preauthorization

and referral requirements in response to

growing market demand for less restrictive

care, they also have implemented

other utilization management strategies

aggressively in an effort to rein in costs.

Many plans have adopted more stringent

utilization management criteria and are

adhering to these standards more strictly.

The result has been a growing number

of denied and downgraded days, which

has angered providers.

Some plans also have increased the

intensity of inpatient utilization management.

Last year, Aetna placed nurses on

site at several hospitals to assist with utilization

management, including discharge

planning, and plans to triple the number

of nurses involved in such utilization

management activities by the end of this

year. Other health plans similarly report

stepped-up activities focusing on discharge

planning. Some hospitals view

these activities as intrusive, but others

reportedly are receptive to having additional

personnel provide assistance,

particularly as hospitals struggle with

a nursing shortage.

Back to Top

State Increases Health Plan

Regulation

any states have increased regulation of the managed care industry

in recent years, but, in comparison with the nationally representative sample

of communities that HSC tracks, New Jersey’s regulation is among the most aggressive.

In the past two years, the New Jersey Legislature has enacted new managed care

laws, adding to the already extensive ones on the books.

A broad patients’ rights law with

various consumer protections was passed

in New Jersey in 1997. The law prohibited

gag clauses and mandated access

to specialists and emergency care. It

also expanded state oversight of health

plans’ financial status. In addition, it

established a health plan report card

that documents patient satisfaction and

plan performance on a variety of clinical

measures. Finally, it imposed financial

sanctions on plans that fail to meet

certain performance standards.

In 1998, New Jersey passed regulations,

which became effective in June 2000,

instituting a 10 percent annual penalty for

late payments by plans to providers and

setting a 45-day time limit for providers

to contest claims. To ensure plans’ financial

solvency and avoid problems similar

to those that caused two high-profile plan

failures in 1998, the state recently established

licensure requirements for provider

organizations accepting certain risk

arrangements. In addition, the state has

required that plans contribute $50 million

to a provider bailout fund to help compensate

providers who were left holding

the bag when the two plans folded. Recently,

the New Jersey Legislature passed one of

the strongest managed care laws in the

nation-one that would permit patients

to sue their health maintenance organizations

(HMOs), and the governor signed

the bill into law.

Plans report that they have been reeling

under the onslaught of New Jersey’s

managed care legislation. One plan executive

estimates he spends 20 to 25 percent

of his time addressing regulatory issues-

far more than he spent five years ago.

Another plan noted that changes under

the state’s new prompt-payment requirement

alone have required information

systems’ investments of $1 million. The

fact that New Jersey has put health plans

on a fast track to implement administrative

simplification requirements in the

federal Health Insurance Portability

and Accountability Act (HIPAA) has

created additional cost pressures. One

plan expects that changes necessary to

become HIPAA compliant will be its

single largest expenditure this year.

The pressure on plans to compete in this tough regulatory environment- particularly

with a mounting need for capital-may lead to further consolidation. Northern New

Jersey experienced some plan consolidation over the past few years due to plan

failures, as well as national mergers such as Aetna’s with US Healthcare and,

more recently, with Prudential. Although 13 plans continue to operate in the area,

market share is concentrated among five. Aetna, the leader in the HMO market,

accounts for almost 40 percent of all enrollees.

Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield

of New Jersey is the only not-for-profit

plan among the top five competitors;

the four others are publicly traded

firms. Competitive pressures may lead

Horizon to renew its efforts, previously

blocked by the state, to convert to for-profit

status. The recent for-profit

conversion of nearby New York City-based

Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield

may lend support to Horizon, if the

plan decides to move in that direction. any states have increased regulation of the managed care industry

in recent years, but, in comparison with the nationally representative sample

of communities that HSC tracks, New Jersey’s regulation is among the most aggressive.

In the past two years, the New Jersey Legislature has enacted new managed care

laws, adding to the already extensive ones on the books.

A broad patients’ rights law with

various consumer protections was passed

in New Jersey in 1997. The law prohibited

gag clauses and mandated access

to specialists and emergency care. It

also expanded state oversight of health

plans’ financial status. In addition, it

established a health plan report card

that documents patient satisfaction and

plan performance on a variety of clinical

measures. Finally, it imposed financial

sanctions on plans that fail to meet

certain performance standards.

In 1998, New Jersey passed regulations,

which became effective in June 2000,

instituting a 10 percent annual penalty for

late payments by plans to providers and

setting a 45-day time limit for providers

to contest claims. To ensure plans’ financial

solvency and avoid problems similar

to those that caused two high-profile plan

failures in 1998, the state recently established

licensure requirements for provider

organizations accepting certain risk

arrangements. In addition, the state has

required that plans contribute $50 million

to a provider bailout fund to help compensate

providers who were left holding

the bag when the two plans folded. Recently,

the New Jersey Legislature passed one of

the strongest managed care laws in the

nation-one that would permit patients

to sue their health maintenance organizations

(HMOs), and the governor signed

the bill into law.

Plans report that they have been reeling

under the onslaught of New Jersey’s

managed care legislation. One plan executive

estimates he spends 20 to 25 percent

of his time addressing regulatory issues-

far more than he spent five years ago.

Another plan noted that changes under

the state’s new prompt-payment requirement

alone have required information

systems’ investments of $1 million. The

fact that New Jersey has put health plans

on a fast track to implement administrative

simplification requirements in the

federal Health Insurance Portability

and Accountability Act (HIPAA) has

created additional cost pressures. One

plan expects that changes necessary to

become HIPAA compliant will be its

single largest expenditure this year.

The pressure on plans to compete in this tough regulatory environment- particularly

with a mounting need for capital-may lead to further consolidation. Northern New

Jersey experienced some plan consolidation over the past few years due to plan

failures, as well as national mergers such as Aetna’s with US Healthcare and,

more recently, with Prudential. Although 13 plans continue to operate in the area,

market share is concentrated among five. Aetna, the leader in the HMO market,

accounts for almost 40 percent of all enrollees.

Horizon Blue Cross Blue Shield

of New Jersey is the only not-for-profit

plan among the top five competitors;

the four others are publicly traded

firms. Competitive pressures may lead

Horizon to renew its efforts, previously

blocked by the state, to convert to for-profit

status. The recent for-profit

conversion of nearby New York City-based

Empire Blue Cross Blue Shield

may lend support to Horizon, if the

plan decides to move in that direction.

Back to Top

Retreat from Managed Care

Strategies

he current HMO penetration rate in

northern New Jersey, 25 percent, is far

lower than the penetration rate in many

other markets nationally. Despite concerns

about the market’s high costs

and high utilization, HMOs have been

slow to make inroads in northern

New Jersey, largely because many large

employers with highly skilled and often

unionized work forces have favored

less restrictive coverage.

Since 1999, plans in the area have

sought to attract enrollment by introducing

more open-access products that

eliminate gatekeeper requirements. In

addition, some plans are considering

developing hybrid products that allow

direct access to specialists, sometimes

within narrower subnetworks. Many are

also scaling back other restrictive product

features such as preauthorization and

referral requirements.

The recent move by some health

plans to more loosely managed products

has been accompanied by plans’ and

providers’ waning interest in risk-contracting

arrangements, which plans

once advocated as an essential strategy

for engaging providers in controlling

costs. Atlantic invested $20 million in

its physician-hospital contracting entity,

Health Resource Partners, only to have it

close two years later after failing to secure

risk contracts from health plans. St.

Barnabas’ physician-hospital contracting

entity, Physician Partnership, also struggled

without risk contracts and has recently

shifted focus to become the exclusive

network of providers for St. Barnabas

employees under its newly formed self-funded

health insurance plan. Physician

Partnership is the sole option for more

than 22,000 St. Barnabas employees and

their dependents; eventually, the plan

may be marketed to local employer

groups interested in direct contracting.

Several hospitals that had pursued

mergers or affiliations with expectations

of growth in risk contracting have abandoned

these relationships. Chilton

Memorial Hospital and Valley Health

System (located just outside the market

area) decided to go their separate ways

in January 2001 because their more than

three-year affiliation failed to yield any

risk-bearing managed care contracts.

Hudson County’s Bayonne Hospital

recently terminated its affiliation with

Atlantic for similar reasons. Some

observers contend that New Jersey’s

new regulations concerning risk arrangements

have contributed to the decline

of such arrangements. Others note that

providers were slow to develop the

infrastructure to accept risk contracts,

and few risk arrangements ever materialized

in the market. he current HMO penetration rate in

northern New Jersey, 25 percent, is far

lower than the penetration rate in many

other markets nationally. Despite concerns

about the market’s high costs

and high utilization, HMOs have been

slow to make inroads in northern

New Jersey, largely because many large

employers with highly skilled and often

unionized work forces have favored

less restrictive coverage.

Since 1999, plans in the area have

sought to attract enrollment by introducing

more open-access products that

eliminate gatekeeper requirements. In

addition, some plans are considering

developing hybrid products that allow

direct access to specialists, sometimes

within narrower subnetworks. Many are

also scaling back other restrictive product

features such as preauthorization and

referral requirements.

The recent move by some health

plans to more loosely managed products

has been accompanied by plans’ and

providers’ waning interest in risk-contracting

arrangements, which plans

once advocated as an essential strategy

for engaging providers in controlling

costs. Atlantic invested $20 million in

its physician-hospital contracting entity,

Health Resource Partners, only to have it

close two years later after failing to secure

risk contracts from health plans. St.

Barnabas’ physician-hospital contracting

entity, Physician Partnership, also struggled

without risk contracts and has recently

shifted focus to become the exclusive

network of providers for St. Barnabas

employees under its newly formed self-funded

health insurance plan. Physician

Partnership is the sole option for more

than 22,000 St. Barnabas employees and

their dependents; eventually, the plan

may be marketed to local employer

groups interested in direct contracting.

Several hospitals that had pursued

mergers or affiliations with expectations

of growth in risk contracting have abandoned

these relationships. Chilton

Memorial Hospital and Valley Health

System (located just outside the market

area) decided to go their separate ways

in January 2001 because their more than

three-year affiliation failed to yield any

risk-bearing managed care contracts.

Hudson County’s Bayonne Hospital

recently terminated its affiliation with

Atlantic for similar reasons. Some

observers contend that New Jersey’s

new regulations concerning risk arrangements

have contributed to the decline

of such arrangements. Others note that

providers were slow to develop the

infrastructure to accept risk contracts,

and few risk arrangements ever materialized

in the market.

Back to Top

Public Insurance Expands, but

Safety Net Is Shaky

ew Jersey recently has made significant

strides in expanding public insurance

coverage, following a period of slow

enrollment in the State Children’s Health

Insurance Program (SCHIP). With a

waiver from the Centers for Medicare and

Medicaid Services-formerly the Health

Care Financing Administration-New

Jersey expanded the program to include

adults with incomes up to 200 percent

of the poverty level. The new program,

known as New Jersey FamilyCare, includes

the 70,000 children originally enrolled

in SCHIP. It also will offer coverage to

125,000 low-income, uninsured adults.

The initial demand for New Jersey

FamilyCare has been overwhelming. In

fact, the volume of applications suggests

that the program is fast approaching its

enrollment cap. State officials are grappling

with whether to use waiting lists or

appropriate more funds to expand the

program to include more people. The

state has been financing its share of the

$200 million program with tobacco settlement

monies, employer contributions

and enrollee premiums. A projected state

budget deficit, however, may severely

constrain the state’s ability to find additional

funding.

Meanwhile, the state-owned safety

net provider in Newark, University

Hospital, has become financially stressed

over the past two years. Though improving

now as intensive efforts take hold, this situation

has prompted the state to consider

possible mergers with other downtown

hospitals-either St. Michael’s Medical

Center (part of Cathedral) or Newark

Beth Israel Medical Center (part of St.

Barnabas). Although both potential

merger partners also are longstanding

safety net providers, there is some concern

that a merger would diminish overall

capacity to care for low-income and

uninsured people, particularly in downtown

Newark.

There also is concern that an imminent

plan to establish a new residency

program at the University of Medicine

and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ)

through the Atlantic Health System will

deplete University Hospital of essential

financial resources and physicians.

UMDNJ is interested in establishing a

suburban affiliation to attract a more

diverse group of residents and compete

more aggressively with academic medical

centers located nearby in New York City

and Philadelphia. For University Hospital,

which has the current local residency

program, such a move could prove challenging.

It might even prompt the state to

move more quickly with its merger plans

for the hospital. ew Jersey recently has made significant

strides in expanding public insurance

coverage, following a period of slow

enrollment in the State Children’s Health

Insurance Program (SCHIP). With a

waiver from the Centers for Medicare and

Medicaid Services-formerly the Health

Care Financing Administration-New

Jersey expanded the program to include

adults with incomes up to 200 percent

of the poverty level. The new program,

known as New Jersey FamilyCare, includes

the 70,000 children originally enrolled

in SCHIP. It also will offer coverage to

125,000 low-income, uninsured adults.

The initial demand for New Jersey

FamilyCare has been overwhelming. In

fact, the volume of applications suggests

that the program is fast approaching its

enrollment cap. State officials are grappling

with whether to use waiting lists or

appropriate more funds to expand the

program to include more people. The

state has been financing its share of the

$200 million program with tobacco settlement

monies, employer contributions

and enrollee premiums. A projected state

budget deficit, however, may severely

constrain the state’s ability to find additional

funding.

Meanwhile, the state-owned safety

net provider in Newark, University

Hospital, has become financially stressed

over the past two years. Though improving

now as intensive efforts take hold, this situation

has prompted the state to consider

possible mergers with other downtown

hospitals-either St. Michael’s Medical

Center (part of Cathedral) or Newark

Beth Israel Medical Center (part of St.

Barnabas). Although both potential

merger partners also are longstanding

safety net providers, there is some concern

that a merger would diminish overall

capacity to care for low-income and

uninsured people, particularly in downtown

Newark.

There also is concern that an imminent

plan to establish a new residency

program at the University of Medicine

and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ)

through the Atlantic Health System will

deplete University Hospital of essential

financial resources and physicians.

UMDNJ is interested in establishing a

suburban affiliation to attract a more

diverse group of residents and compete

more aggressively with academic medical

centers located nearby in New York City

and Philadelphia. For University Hospital,

which has the current local residency

program, such a move could prove challenging.

It might even prompt the state to

move more quickly with its merger plans

for the hospital.

Back to Top

Issues to Track

inancial pressures continue to plague

many northern New Jersey hospitals,

leaving some downtown facilities in a

particularly precarious condition and

threatening their capacity to care for low-income

and uninsured people. Health

plans’ financial condition has generally

stabilized, but competitive pressures in an

intense state regulatory environment may

promise change in the plan sector as well.

As plans attempt to restore profitability

and respond to consumer demand for

less restrictive products, it is likely that

employers will face escalating premiums,

making health insurance coverage more

costly. And although New Jersey has

successfully expanded public insurance

options through New Jersey FamilyCare,

state budget constraints may ultimately

limit the reach of this program.

These observations suggest several

important issues to track: inancial pressures continue to plague

many northern New Jersey hospitals,

leaving some downtown facilities in a

particularly precarious condition and

threatening their capacity to care for low-income

and uninsured people. Health

plans’ financial condition has generally

stabilized, but competitive pressures in an

intense state regulatory environment may

promise change in the plan sector as well.

As plans attempt to restore profitability

and respond to consumer demand for

less restrictive products, it is likely that

employers will face escalating premiums,

making health insurance coverage more

costly. And although New Jersey has

successfully expanded public insurance

options through New Jersey FamilyCare,

state budget constraints may ultimately

limit the reach of this program.

These observations suggest several

important issues to track:

- Will New Jersey’s hospitals achieve

financial stability, and, if so, at what

price for the safety net?

- How will health plans continue to deal

with mounting cost pressures? Will

plans continue to withdraw from the

Medicare and Medicaid markets? Will

another wave of plan consolidation

materialize?

- How will employers respond to rising

premiums? Will employers increase cost

sharing for employees? Will greater

pressure emerge to control costs and

utilization, and, if so, how will plans

respond?

- How will the state deal with the overwhelming

demand for coverage under

New Jersey FamilyCare? Will the state’s

projected budget deficit limit this program’s

potential?

Back to Top

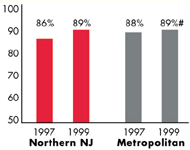

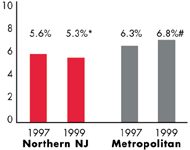

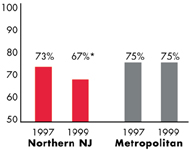

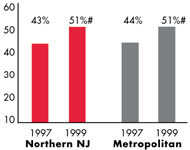

Northern New Jersey’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997 and 1999

Back to Top

Background and Observations

| Northern New Jersey Demographics |

| Northern New Jersey |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

Population, July 1, 19991

1,954,671 |

| Population Change, 1990-19992

|

| 2.0% |

8.6% |

| Median Income3 |

| $32,890 |

$27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 |

| 10% |

14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 |

| 14% |

11% |

Sources:

1. US Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates

2. US Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates

3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 |

| Health Insurance Status |

| Northern New Jersey |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 |

| 12% |

15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1

|

| 8% |

11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that

Offer Coverage2 |

| 84% |

84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage

under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 |

| $198 |

$181 |

Sources:

1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999

2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

| Health System Characteristics |

| Northern New Jersey |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1

|

| 3.8 |

2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2

|

| 2.6 |

2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 |

| 17% |

32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 |

| 25% |

36% |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 1998

2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians,

except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists)

3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1

4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

Back to Top

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are

representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60

communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents

the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit

and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue

Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are

available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Northern New Jersey Community Report:

Debra A. Draper, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Linda R. Brewster, HSC

Lawrence D. Brown, Columbia University

Lance Heineccius, University of Washington

Carolyn A. Watts, University of Washington

Elizabeth Eagan, HSC

Leslie Jackson, HSC

Marie C. Reed, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group

|