Physicians More Likely to Face Quality Incentives than Incentives That May Restrain Care

Issue Brief No. 48

January 2002

Jeffrey Stoddard, Joy M. Grossman, Liza Rudell

Intent of Incentives

![]() ith the growth of managed care,

health plans and physician organizations

have adopted formal financial

incentives to influence physician

clinical decision making. Critics contend

incentives can create a conflict of

interest between physicians’ personal

financial gain and their patients’ best

interests, which could compromise

quality and patient trust. Supporters

counter that incentives to encourage

cost-effective care are necessary to

hold down overuse of services that

fuel runaway costs. Approaches such

as capitation-a fixed monthly per-patient

payment-and profiling are

the most controversial because they

can potentially lead to the denial of

necessary services.

ith the growth of managed care,

health plans and physician organizations

have adopted formal financial

incentives to influence physician

clinical decision making. Critics contend

incentives can create a conflict of

interest between physicians’ personal

financial gain and their patients’ best

interests, which could compromise

quality and patient trust. Supporters

counter that incentives to encourage

cost-effective care are necessary to

hold down overuse of services that

fuel runaway costs. Approaches such

as capitation-a fixed monthly per-patient

payment-and profiling are

the most controversial because they

can potentially lead to the denial of

necessary services.

While much attention has been focused on how health plans pay physician organizations, little is known about how physician organizations pay individual physicians. But, the financial incentives used by practices to determine individual physician compensation are likely to have stronger effects on care delivery, particularly when they are based on the physician’s own clinical performance rather than the financial performance of the group as a whole.1 Physician practices use such approaches to align the interests of individual physicians with those of the group.

This Issue Brief examines four factors used to adjust base compensation and/or bonuses that reflect how physicians treat their patients. These are productivity (a standard measure) and three performance-based measures: results of patient satisfaction surveys, quality of care measures and profiling that compares a physician’s pattern of medical resource use to that of other physicians.

Trends in Use

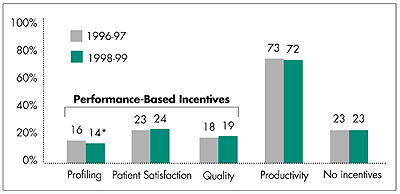

![]() ost physicians are not directly subject to the types of incentives

that are perceived to conflict with patients’ interests (see

Figure 1). In 1999, physicians in practices of two or more said they are less

often subject to financial incentives based on profiling (14 percent), which are

more likely to restrain use of services, than incentives based on patient satisfaction

(24 percent) and quality (19 percent), which are more likely to encourage use.

ost physicians are not directly subject to the types of incentives

that are perceived to conflict with patients’ interests (see

Figure 1). In 1999, physicians in practices of two or more said they are less

often subject to financial incentives based on profiling (14 percent), which are

more likely to restrain use of services, than incentives based on patient satisfaction

(24 percent) and quality (19 percent), which are more likely to encourage use.

Overall, physicians are much less likely to face performance-based incentives (32 percent) than the productivity incentives that have traditionally been used to determine compensation (72 percent). Performance-based incentives are often used in combination with each other and almost always in combination with productivity incentives. The prevalence in the use of financial incentives has remained remarkably stable between 1997 and 1999, with a modest but statistically significant decline in profiling.

Figure 1

Percentage of Physicians in Practices of Two or More Whose

Compensation Is Affected by Selected Financial Incentives

* Significant change at p<0.05 between 1996-97 and 1998-99.

Note: Sample excludes full owners of solo practices, physicians spending

less than 60 percent of their time in patient care and physicians practicing

in community health centers and city-, county- or state-owned hospitals

and clinics. Physicians may be subject to more than one incentive.

Source: Community Tracking Study Physician Survey, 1996-97 and 1998-99

Differences Across Practice Type

![]() roductivity incentives are widespread and exist across all

practice arrangements (see Table 1). While performance-based

incentives have not been widely adopted, they are much more prevalent in certain

types of practices. Physicians in group/staff-model health maintenance organizations

(HMOs) are more than three times as likely to be subject to profiling incentives

as those practicing in small or medium-sized groups and are even more likely to

be subject to patient satisfaction and/or quality incentives. Physicians in large

groups of 30 or more and those in hospital-owned and medical school practices

are also significantly more likely to face these incentives than physicians in

smaller groups, but are only about half as likely as group/staff-model HMO physicians

to do so.

roductivity incentives are widespread and exist across all

practice arrangements (see Table 1). While performance-based

incentives have not been widely adopted, they are much more prevalent in certain

types of practices. Physicians in group/staff-model health maintenance organizations

(HMOs) are more than three times as likely to be subject to profiling incentives

as those practicing in small or medium-sized groups and are even more likely to

be subject to patient satisfaction and/or quality incentives. Physicians in large

groups of 30 or more and those in hospital-owned and medical school practices

are also significantly more likely to face these incentives than physicians in

smaller groups, but are only about half as likely as group/staff-model HMO physicians

to do so.

Pressures to implement formal incentives may be stronger for group/staff-model HMOs, large groups and hospital-owned and medical school practices than for small and medium-sized group practices. This may be because these practices:

- are larger and may have more difficulty

monitoring individual physicians informally;

- have greater need to align group and

individual objectives since physicians are

more likely to be salaried employees; and/or

- are more likely to have health plan contracts with capitation or similar incentives and have more resources and data to develop performance-monitoring systems.

| Table 1 Percentage of Physicians Whose Compensation Is Affected by Selected Financial Incentives by Practice Arrangement, 1999 |

||||

| Percent of Physicians

in Practices of Two or More, By Practice Arrangement |

Incentives Based

on Individual Physician Performance |

|||

| Performance- Based |

Productivity |

|||

| Practice Arrangement | |

Profiling |

Patient Satisfaction and/or

Quality |

|

| Small Group (2-9 Physicians) | 42% |

10% |

16% |

72% |

| Medium Group (10-29 Physicians) | 10 |

10 |

18 |

70 |

| Large Group (30+ Physicians) | 8 |

14* |

32** |

81** |

| Staff/Group HMO | 7 |

33** |

70** |

65* |

| Hospital-Owned, Medical School or Other | 33 |

16** |

37** |

72 |

| All | 100 |

14 |

29 |

72 |

| * Significantly different from small groups

at p<0.05. ** Significantly different from small groups at p<0.001. Note: Sample excludes full owners of solo practices, physicians spending less than 60 percent of their time in patient care and physicians practicing in community health centers and city-, county- or state-owned hospitals and clinics. Physicians may be subject to more than one incentive. Source: Community Tracking Study Physician Survey, 1998-99 |

||||

Capitation and Individual Financial Incentives

![]() hysicians working in practices with higher levels of capitated

revenue are more likely to be subject to performance-based incentives than those

with less capitated revenue (see Table 2). Those in practices

with more than 50 percent capitation are three times as likely as those in practices

with no capitation to use profiling and more than twice as likely to use patient

satisfaction and/or quality incentives.

hysicians working in practices with higher levels of capitated

revenue are more likely to be subject to performance-based incentives than those

with less capitated revenue (see Table 2). Those in practices

with more than 50 percent capitation are three times as likely as those in practices

with no capitation to use profiling and more than twice as likely to use patient

satisfaction and/or quality incentives.

Under capitation, practices have incentives to use profiling to promote cost-effective patterns of care. Patient satisfaction and quality incentives, on the other hand, may be implemented to offset the potential risk under capitation to withhold medically necessary services.

| Table 2 Percentage of Physicians Whose Compensation Is Affected by Selected Financial Incentives, by Percentage of Practice Revenue from Capitation, 1999 |

||||

| |

Incentives Based

on Individual Physician Performance |

|||

| Performance-Based |

Productivity* |

|||

| Percentage of Practive Revenue From Capitation | |

Profiling* |

Patient Satisfaction and/or

Quality* |

|

| None | 39% |

8% |

19% |

71% |

| 1-24 | 30 |

13 |

27 |

74 |

| 25-49 | 14 |

22 |

34 |

77 |

| 50+ | 17 |

25 |

50 |

67 |

| All | 100 |

14 |

29 |

72 |

| * All comparisons are significant for linear

trend at p<0.001. Note: Sample excludes full owners of solo practices, physicians spending less than 60 percent of their time in patient care, and physicians practicing in community health centers and city-, county- or state-owned hospitals and clinics. Physicians may be subject to more than one incentive. Source: Community Tracking Study Physician Survey, 1998-99 |

||||

Policy Implications

![]() lthough there is little evidence that financial incentives

result in the withholding of necessary care, many states have passed laws governing

physician incentives, and Medicare has issued regulations barring health plans

from paying physicians to reduce or limit medically necessary services to individual

patients. Additionally, various patient-protection proposals pending in Congress

mirror Medicare regulations governing physician incentives.

lthough there is little evidence that financial incentives

result in the withholding of necessary care, many states have passed laws governing

physician incentives, and Medicare has issued regulations barring health plans

from paying physicians to reduce or limit medically necessary services to individual

patients. Additionally, various patient-protection proposals pending in Congress

mirror Medicare regulations governing physician incentives.

However, there is some evidence that incentives may be compromising patients’ trust in physicians because of potential conflicts of interest.2 As an alternative to barring such incentives, some patient-protection laws require health plans to disclose financial incentives or allow lawsuits when incentives are alleged to have resulted in withholding needed care. Many consumer advocates believe patients are entitled to disclosure and that they can make better choices about selecting physicians and treatment decisions if they are informed about the nature of the financial incentives.

Nevertheless, existing regulations focusing on health plans do not take into account incentives established by physician practices, even though they are more powerful and may augment or blunt plan incentives, particularly in large practices. However, policy makers need to think carefully about whether regulating physician organizations and incentives at the practice level makes sense, given their low prevalence and the challenge of implementing regulation at that level.

Instead of direct regulation of incentives, another approach is public disclosure of their use. Comprehensive disclosure of incentives at both the physician and practice level is very complex. Incentives can differ in terms of their relative importance and, in some cases, even conflict with each other. For example, profiling or other cost-control incentives could conflict with quality incentives, and productivity incentives with patient satisfaction incentives. Moreover, the effects of all of this on patient care are uncertain. Finally, communicating this information coherently to consumers is an enormous challenge.3, 4

There was almost no change in the use of incentives by physician practices between 1997 and 1999, and significant growth in their use seems unlikely in the short term. Furthermore, the managed care backlash has driven a decline in primary care physician employment in group/staff-model HMOs5 and a slowdown or decline in capitation6 (although these trends may be offset to some degree by continuing growth of the number of physician employees and growing practice size). Given this outlook on the use of incentives, policy makers need to carefully consider whether intervention is warranted.

Data Sources

![]() his Issue Brief presents findings

from HSC’s Community Tracking

Study Physician Survey conducted

in 1996-97 and 1998-99. It is a

nationally representative telephone

survey of non-federal, patient care

physicians who spend at least 20

hours a week in direct patient care.

The 1996-97 survey included 12,528

physicians and had a 65 percent

response rate. The 1998-99 survey

included 12,304 physicians and had

a 61 percent response rate.

his Issue Brief presents findings

from HSC’s Community Tracking

Study Physician Survey conducted

in 1996-97 and 1998-99. It is a

nationally representative telephone

survey of non-federal, patient care

physicians who spend at least 20

hours a week in direct patient care.

The 1996-97 survey included 12,528

physicians and had a 65 percent

response rate. The 1998-99 survey

included 12,304 physicians and had

a 61 percent response rate.

Notes

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Richard Sorian

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added

to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549

(for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261

(for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org