Prescription Drug Access: Not Just a Medicare Problem

Issue Brief No. 51

April 2002

Peter J. Cunningham

![]() hile all state Medicaid programs provide outpatient prescription drug coverage,

slightly more than one in four Medicaid patients ages 18-64 could not afford to fill

at least one prescription in the last year, according to a new study by the Center for

Studying Health System Change (HSC). A similar percentage of uninsured adults

also had difficulty affording prescription medications. Faced with rapidly rising

drug spending, many states have moved to control Medicaid prescription drug

spending by imposing copayments, limiting the number of prescriptions and using

other cost-containment methods. The study indicates that these state cost-control

measures are contributing to Medicaid beneficiaries’ prescription drug access problems.

State and federal policy makers should keep in mind that the impact of these

controls on Medicaid beneficiaries is likely to be greater than on privately insured

people, given their higher need and lower incomes.1

hile all state Medicaid programs provide outpatient prescription drug coverage,

slightly more than one in four Medicaid patients ages 18-64 could not afford to fill

at least one prescription in the last year, according to a new study by the Center for

Studying Health System Change (HSC). A similar percentage of uninsured adults

also had difficulty affording prescription medications. Faced with rapidly rising

drug spending, many states have moved to control Medicaid prescription drug

spending by imposing copayments, limiting the number of prescriptions and using

other cost-containment methods. The study indicates that these state cost-control

measures are contributing to Medicaid beneficiaries’ prescription drug access problems.

State and federal policy makers should keep in mind that the impact of these

controls on Medicaid beneficiaries is likely to be greater than on privately insured

people, given their higher need and lower incomes.1

- Nonelderly Have Problems Affording Drugs

- Low Income, Poor Health Compound Problems

- Cost Containment Linked to Access Gaps

- Policy Implications

- Data Source

- Notes

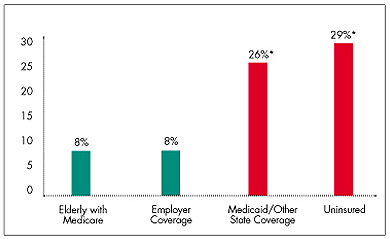

Nonelderly Have Problems Affording Drugs

![]() hile recent federal and state policy

debates have focused on the prescription

drug needs of the elderly in

Medicare, many nonelderly adults also

have problems affording prescription

medications. According to HSC’s

2000-01 Community Tracking Study

Household Survey, nonelderly adults

enrolled in Medicaid and those who

are uninsured have the most problems

affording prescription drugs—more

than one out of four people in both

groups did not get at least one prescription

drug in the past year due

to the cost. This is in sharp contrast

to those in Medicare and those with

employer-sponsored private insurance (see Figure 1).

hile recent federal and state policy

debates have focused on the prescription

drug needs of the elderly in

Medicare, many nonelderly adults also

have problems affording prescription

medications. According to HSC’s

2000-01 Community Tracking Study

Household Survey, nonelderly adults

enrolled in Medicaid and those who

are uninsured have the most problems

affording prescription drugs—more

than one out of four people in both

groups did not get at least one prescription

drug in the past year due

to the cost. This is in sharp contrast

to those in Medicare and those with

employer-sponsored private insurance (see Figure 1).

The fact that adults with Medicaid coverage have problems affording prescription drugs is surprising. Medicaid is designed to ensure access to affordable medical care for the poorest and sickest Americans, and all state Medicaid programs provide drug coverage for most beneficiaries.2 The wide gap in access to prescription drugs between nonelderly Medicaid enrollees and those with employer-sponsored coverage stands in contrast to other types of care. For example, people with Medicaid are more similar to those with employer-sponsored coverage in terms of unmet medical needs, having a usual source of care and contact with a physician in the past year.

Figure 1

Percent Not Obtaining Prescription Drug Due to Cost

* Difference from elderly with Medicare is statistically significant at p<.05

level.

Note: The categories of employer coverage, Medicaid coverage and the

uninsured include adults ages 18-64.

Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01

Low Income, Poor Health Compound Problems

![]() espite the assistance Medicaid

brings, beneficiaries’ low incomes put

them at much higher risk of being

unable to afford prescription drugs.

Half of nonelderly adult Medicaid

beneficiaries have incomes below the

federal poverty level, or $8,590 for a

single person in 2001 (see Table 1);

three-quarters have incomes below

200 percent of poverty. By contrast,

only 3 percent of people with

employer-sponsored health coverage

have incomes below the poverty level,

while 14 percent have incomes below

200 percent of poverty.

espite the assistance Medicaid

brings, beneficiaries’ low incomes put

them at much higher risk of being

unable to afford prescription drugs.

Half of nonelderly adult Medicaid

beneficiaries have incomes below the

federal poverty level, or $8,590 for a

single person in 2001 (see Table 1);

three-quarters have incomes below

200 percent of poverty. By contrast,

only 3 percent of people with

employer-sponsored health coverage

have incomes below the poverty level,

while 14 percent have incomes below

200 percent of poverty.

Medicaid beneficiaries also tend to be in poorer health. More than half of nonelderly adult beneficiaries are living with at least one chronic condition, such as diabetes, heart disease or depression, and more than one in four has two or more such conditions. In contrast, fewer than one-third of people with employer-sponsored coverage have a chronic condition, and only 10 percent have two or more conditions.

Cost barriers are greater for people living with chronic conditions across all categories of insurance coverage (see Table 2). Especially striking is the high proportion of Medicaid beneficiaries and uninsured people with chronic health conditions who report being unable to afford prescription drugs. Perhaps most troubling, more than 40 percent of Medicaid patients with two or more chronic conditions reported not obtaining prescription medications because of cost.

Thus, low incomes and high prevalence of health problems put adult Medicaid beneficiaries at high risk for experiencing problems in affording prescription medications. The study shows that these characteristics largely explain the wide gap between Medicaid and privately insured persons when it comes to affording prescription medications. But why has Medicaid—which was designed to narrow this gap—failed in this one critical aspect of care?

| Table 1 Health and Income Characteristics by Insurance Type (ages 18-64) |

|||

| Medicaid/Other State

Coverage |

Uninsured |

Employer-Sponsored

Coverage |

|

| Percent With Incomes Below Poverty | 50% |

26% |

3% |

| Percent With Incomes Between 100% and 200% of Poverty | 25 |

30 |

11 |

| Percent With 1 Chronic Condition* | 23 |

14 |

20 |

| Percent With 2 or More Chronic Conditions* | 29 |

6 |

10 |

| * Conditions asked about in the

survey include diabetes, arthritis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease, hypertension, coronary heart disease, cancer, benign prostate disease,

depression and other serious medical problems that limit usual activities. Note: Estimates reflect the percentage who responded “yes”to the following question: “During the past 12 months, was there any time you needed prescription medicines but didn’t get them because you couldn’t afford it?” Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01 |

|||

| Table 2 Percent Not Obtaining Prescription Drugs Due to Cost, by Insurance Coverage and Chronic Condition Status for Nonelderly Adults (ages 18-64) |

|||

| No Chronic Conditions |

1 Chronic Condition* |

2 or More Chronic

Conditions* |

|

| All Persons Ages 18-64 | 10% |

17%** |

25%** |

| Employer-Sponsored Coverage | 6 |

11** |

15** |

| Medicaid and Other State Coverage | 16 |

26** |

41** |

| Uninsured | 23 |

48** |

61** |

| * Conditions asked about in the

survey include diabetes, arthritis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary

disease, hypertension, coronary heart disease, cancer, benign prostate disease,

depression and other serious medical problems that limit usual activities. ** Difference from persons with no chronic conditions is statistically significant at p<.05 level. Note: Estimates reflect the percentage who responded “yes”to the following question: “During the past 12 months, was there any time you needed prescription medicines but didn’t get them because you couldn’t afford it?” Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01 |

|||

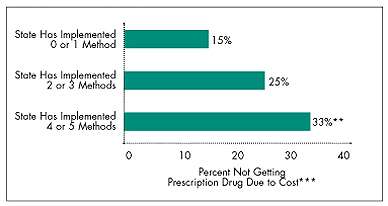

Cost Containment Linked to Access Gaps

![]() tate efforts to control Medicaid prescription drug spending

appear to contribute to the access problems experienced by Medicaid patients.

In the past few years, many states have implemented a variety of methods to

control escalating Medicaid prescription drug spending. These methods attempt

to control spending by influencing physicians’ prescribing patterns and patients’

drug use.

tate efforts to control Medicaid prescription drug spending

appear to contribute to the access problems experienced by Medicaid patients.

In the past few years, many states have implemented a variety of methods to

control escalating Medicaid prescription drug spending. These methods attempt

to control spending by influencing physicians’ prescribing patterns and patients’

drug use.

Although methods vary from state to state, the most common include imposing nominal copayments, setting dispensing limits that restrict the number of prescriptions, mandating substitution of generic drugs for brand-name drugs, requiring prior authorization for certain drugs and issuing step-therapy protocols that require physicians to try lower-cost drugs before prescribing more costly alternatives.3

Individually, these cost controls do not appear to significantly affect beneficiaries’ access to prescription drugs. Most states, however, have implemented more than one cost-control measure, and the study shows that when multiple cost-control measures are implemented, beneficiary access to prescription drugs is affected to a much greater extent (even after controlling for beneficiary characteristics and other community, state and regional factors). For example, beneficiaries in states that have implemented four or five cost-control measures were about twice as likely to report cost barriers as those living in states with either one or no cost-control policies (see Figure 2).

States that implement multiple cost-control methods may be much more aggressive in trying to control Medicaid prescription drug spending. Not only would the cumulative effects of implementing these policies curtail access to a greater degree than any single method, but the individual methods themselves also may be more stringent (e.g., higher copayments, stricter dispensing limits) in states that are trying more aggressively to control spending. While greater Medicaid savings may be realized, an unintended consequence of aggressive cost-control policies might be a reduction in beneficiary access to needed prescription drugs.

Figure 2

Summary of Effects of State Medicaid Cost-Control Methods on Beneficiaries’

Access to Prescription Drugs*

* These methods include copayments, limits on the number of prescriptions, mandatory substitution of generics for brand-name

drugs, preauthorization requirements and step-therapy requirements.

** Difference from persons in states that have implemented 0 or 1 requirement is statistically significant at p<.05.

*** Estimates reflected regression-adjusted means that control for beneficiary characteristics and other community, state and regional

factors.

Note: Sample includes persons ages 18-64 enrolled in Medicaid or state

coverage programs.

Source: Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2000-01

Policy Implications

![]() hile the recent policy debate has focused

on expanding prescription drug coverage

for senior citizens enrolled in Medicare,

the HSC study suggests that policy makers

should not ignore the difficulties many

nonelderly patients face in affording drugs,

especially those who are uninsured or

enrolled in Medicaid.

hile the recent policy debate has focused

on expanding prescription drug coverage

for senior citizens enrolled in Medicare,

the HSC study suggests that policy makers

should not ignore the difficulties many

nonelderly patients face in affording drugs,

especially those who are uninsured or

enrolled in Medicaid.

The importance of prescription drugs in medical care is growing as both the number of people using prescription drugs and the number of prescriptions per user are increasing.4 Expenditures for prescription drugs now account for about 11 percent of personal health care expenses, up from about 6 percent in 1988.5 The importance and cost of prescription drugs in medical care are likely to increase in the future with the development of new drug products, including those from the still-nascent biotechnology field. As drug products increase in both importance and cost, policy makers will be confronted with the challenge of making medications affordable and accessible to all Americans.

Many states currently are experiencing Medicaid budget shortfalls, and state officials often point to rising Medicaid prescription drug spending as a major cause. If these pressures continue or worsen, states may become even more aggressive in their efforts to control prescription drug expenditures, further restricting beneficiary access. While some may view these cost-control methods as consistent with those used by many private insurers, public officials should keep in mind that the impact of these methods on Medicaid beneficiaries is likely to be greater given their higher need and lower incomes.

Data Source

This Issue Brief presents findings from the 2000-01 Community Tracking Study Household Survey,a nationally representative telephone survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population, supplemented by in-person interviews of households without telephones to ensure proper representation. The survey contains observations on a total of about 60,000 persons. The sample for this study is based on 39,000 adults ages 18-64, including about 1,800 who are in Medicaid or state coverage. The response rate for the survey was around 60 percent.

Notes

| 1. | This Issue Brief is based on Research Report No.5,"Affording Prescription Drugs—Not Just a Problem for the Elderly," which can be found here. |

| 2. | While prescription drugs are an optional benefit under Medicaid, all 50 states and the District of Columbia now offer such coverage. |

| 3. | Schwalberg, Renee, et al., Medicaid Outpatient Prescription Drug Benefits: Findings from a National Survey and Selected Case Study Highlights, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (October 2001); Bruen, Brian K., States Strive to Limit Medicaid Expenditures for Prescribed Drugs, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured (February 2002). |

| 4. | Merlis, Mark, "Explaining the Growth in Prescription Drug Spending: A Review of Recent Studies," report prepared for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Conference on Pharmaceutical Pricing Practices, Utilization, and Costs (August 2000). |

| 5. | Levit, Katherine, et al., "Inflation Spurs Health Spending in 2000," Health Affairs,Vol. 21, No. 1 (January/February 2002). |

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Richard Sorian

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added

to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549

(for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261

(for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org