The Insurance Gap and Minority Health Care, 1997-2001

Tracking Report No. 2

June 2002

J. Lee Hargraves

![]() aps in access to medical care among working-age white

Americans, African Americans and Latinos failed to improve between 1997 and

2001, despite a booming economy and increased national attention to narrowing

and eliminating minority health disparities. African Americans and Latinos continue

to have less access to a regular health care provider, see a doctor less often

and lag behind whites in seeing specialists, according to recent findings from

the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). Ethnic and racial disparities

in access among uninsured Americans are much greater than disparities among

the insured. Uninsured whites’ greater financial resources may explain why they

have fewer problems accessing care. Eliminating disparities in minority health

care will be difficult without first eliminating these gaps in minority health

insurance.

aps in access to medical care among working-age white

Americans, African Americans and Latinos failed to improve between 1997 and

2001, despite a booming economy and increased national attention to narrowing

and eliminating minority health disparities. African Americans and Latinos continue

to have less access to a regular health care provider, see a doctor less often

and lag behind whites in seeing specialists, according to recent findings from

the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). Ethnic and racial disparities

in access among uninsured Americans are much greater than disparities among

the insured. Uninsured whites’ greater financial resources may explain why they

have fewer problems accessing care. Eliminating disparities in minority health

care will be difficult without first eliminating these gaps in minority health

insurance.

- Disturbing Disparities Continue

- Regular Health Care Provider

- Access To Physicians

- Reliance On Emergency Rooms

- Lack Of Coverage Fuels Disparities

- Persistent Problems Among Latinos

- Uninsured Minorities Have Lower Incomes

- Coverage Counts Most

- Data Sources

- Notes

- Web-Exclusive Tables

Disturbing Disparities Continue

![]() wo troubling trends persisted between 1997 and 2001:

African Americans and Latinos continued to have significantly

less access to medical care than white Americans,

and minorities without insurance had much more

difficulty getting care than did uninsured whites. Lack

of health insurance plays a critical role in these ongoing

racial and ethnic health care disparities.

wo troubling trends persisted between 1997 and 2001:

African Americans and Latinos continued to have significantly

less access to medical care than white Americans,

and minorities without insurance had much more

difficulty getting care than did uninsured whites. Lack

of health insurance plays a critical role in these ongoing

racial and ethnic health care disparities.

Reduced access to medical care can lead to delays in diagnosis and treatment and contribute to well-documented disparities in minority health.1 According to a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report, death rates for whites, African Americans and Latinos from many common diseases have declined during the last decade.2 The CDC also reports, however, that "relatively little progress was made toward the goal of eliminating racial/ethnic disparities" among a wide range of health status indicators. In other words, while all Americans are healthier, the gaps between minority groups and whites remain nearly the same as a decade ago.

In assessing minority health care disparities, this report examines four measures of access among whites, blacks and Latinos:

- whether people have a regular health care provider;

- whether people saw a doctor in the last year;

- whether people had access to specialists; and

- use of emergency rooms for outpatient care.

Back to Top

Regular Health Care Provider

![]() eople with a regular provider are connected to the health

care system and have better access to and coordination of care.3

The percentage of Latinos with a regular provider declined from 59.6 percent

in 1997 to 55.4 percent in 2001. During the same time, the percentage of whites

and African Americans with a regular care provider remained stable. In 2001,

African Americans and Latinos were less likely to identify a regular provider

than were whites, a disparity virtually unchanged from 1997 (see

Table 1). Overall, about three-quarters of whites reported having a regular

provider, compared with slightly less than two-thirds of African Americans and

a little over half of Latinos.

eople with a regular provider are connected to the health

care system and have better access to and coordination of care.3

The percentage of Latinos with a regular provider declined from 59.6 percent

in 1997 to 55.4 percent in 2001. During the same time, the percentage of whites

and African Americans with a regular care provider remained stable. In 2001,

African Americans and Latinos were less likely to identify a regular provider

than were whites, a disparity virtually unchanged from 1997 (see

Table 1). Overall, about three-quarters of whites reported having a regular

provider, compared with slightly less than two-thirds of African Americans and

a little over half of Latinos.

| TABLE 1: Access Among African Americans, Latinos and Whites | |||

| 1997 |

1999 |

2001 |

|

| Has a Regular Health Care Provider | |||

| African American | 63.9% |

65.5% |

64.4% |

| Latino | 59.6 |

56.2* |

55.4 # |

| White | 74.8 |

73.9* |

75.2* |

| Had a Doctor Visit in the Last 12 Months | |||

| African American | 74.6 |

77.4* |

74.1* |

| Latino | 62.0 |

65.5* |

62.2* |

| White | 77.6 |

78.4* |

79.1 # |

| Last Doctor Visit Was to a Specialist | |||

| African American | 26.0 |

23.4* |

24.4 |

| Latino | 23.2 |

25.1 |

23.3 |

| White | 27.5 |

27.7 |

27.7 |

| Proportion of Visits with Health Care Providers in the ER | |||

| African American | 10.4 |

10.7 |

9.6* |

| Latino | 7.4 |

6.8 |

7.8 |

| White | 6.8 |

6.8 |

6.6 |

| Notes: Bold text shows statistically

significant differences from whites. * Change from previous survey is statistically significant at p<.05. # Change from 1997-2001 is statistically significant at p<.05. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey |

|||

Back to Top

Access To Physicians

![]() reventive care and early detection of disease are made possible

via visits to physicians. In addition to lack of a regular

health care provider, racial and ethnic disparities in physician

visits continue. Latinos and blacks were less likely

than whites to have seen a physician in the last 12 months.

In fact, while the percentage of whites with at least one physician

visit increased slightly, from 77.6 percent in 1997 to 79.1

percent in 2001, the portion of blacks and Latinos seeing

a doctor remained unchanged. Overall, one in five whites

reported not seeing a doctor in the previous year, compared

with two in five Latinos and one in four African Americans.

reventive care and early detection of disease are made possible

via visits to physicians. In addition to lack of a regular

health care provider, racial and ethnic disparities in physician

visits continue. Latinos and blacks were less likely

than whites to have seen a physician in the last 12 months.

In fact, while the percentage of whites with at least one physician

visit increased slightly, from 77.6 percent in 1997 to 79.1

percent in 2001, the portion of blacks and Latinos seeing

a doctor remained unchanged. Overall, one in five whites

reported not seeing a doctor in the previous year, compared

with two in five Latinos and one in four African Americans.

Another important measure of access to care is the likelihood of seeing a specialist. Access to specialists may indicate proper care for patients with complex conditions. In some cases, however, increased use of specialists for routine care may signal inappropriate and costlier care. During 1997-2001, African Americans and Latinos generally had less access to specialists than did whites. In 2001, whites were more likely to have reported their last doctor visit was to a specialist than either African Americans or Latinos. Almost 28 percent of whites’ most recent physician visits were to a specialist in 2001, compared with slightly over 24 percent for African Americans and 23 percent for Latinos.

Back to Top

Reliance On Emergency Rooms

![]() or many Americans, hospital emergency rooms provide

essential access to medical care, but treating people with

nonurgent conditions in emergency rooms is costly, less

effective and may jeopardize access for people with life-threatening

conditions. Both Latinos and African Americans

made more of their health care provider visits to emergency

rooms than whites, illustrating the possible consequences

of less access in other health care settings. In

2001, 6.6 percent of visits among whites occurred in

emergency rooms, compared with 7.8 percent of Latinos’

visits and 9.6 percent of African Americans’ visits.

or many Americans, hospital emergency rooms provide

essential access to medical care, but treating people with

nonurgent conditions in emergency rooms is costly, less

effective and may jeopardize access for people with life-threatening

conditions. Both Latinos and African Americans

made more of their health care provider visits to emergency

rooms than whites, illustrating the possible consequences

of less access in other health care settings. In

2001, 6.6 percent of visits among whites occurred in

emergency rooms, compared with 7.8 percent of Latinos’

visits and 9.6 percent of African Americans’ visits.

Back to Top

Lack Of Coverage Fuels Disparities

![]() uring 1997-2001, African Americans and Latinos were less

likely than whites to have health insurance. In each year of the HSC Household

Survey, the percentage of uninsured whites declined slightly, dropping from

12.5 percent in 1997 to 10.9 percent in 2001. The proportion of uninsured blacks

and Latinos, however, remained relatively stable (see Table

2). In 2001, almost one in three Latinos and one in five African Americans

lacked health insurance, compared with one in 10 whites.

uring 1997-2001, African Americans and Latinos were less

likely than whites to have health insurance. In each year of the HSC Household

Survey, the percentage of uninsured whites declined slightly, dropping from

12.5 percent in 1997 to 10.9 percent in 2001. The proportion of uninsured blacks

and Latinos, however, remained relatively stable (see Table

2). In 2001, almost one in three Latinos and one in five African Americans

lacked health insurance, compared with one in 10 whites.

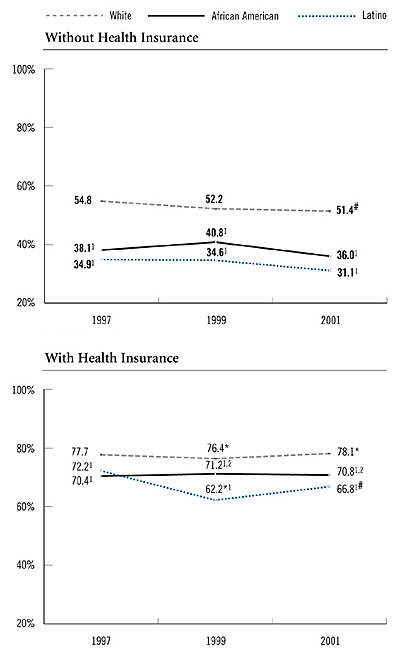

Uninsured African Americans and Latinos were consistently less likely than uninsured whites to have a regular health care provider. Half of uninsured whites had a regular provider, compared with about one-third of Latinos and African Americans. The gaps between uninsured minorities and uninsured whites generally were almost double the gaps between insured minorities and insured whites, suggesting health insurance plays a far more important role in the ability of minorities to access care.

In 2001, for example, the difference between uninsured whites and uninsured African Americans with a regular provider was greater than 15 percentage points. This disparity compares with a gap of less than 8 percentage points between insured whites and insured African Americans. The access gap between uninsured Latinos and uninsured whites was more than 20 percentage points, almost double the 11 percentage point difference between insured Latinos and insured whites (see Figure 1).

| TABLE 2: Working-Age Adults Without Health Insurance | |||

| 1997 |

1999 |

2001 |

|

| African American | 20.1% |

18.9% |

18.7% |

| Latino | 33.7 |

31.8 |

32.0 |

| White* | 12.5 |

11.9 |

10.9 |

| * Decrease each year for whites was statistically

significant. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey |

|||

FIGURE 1: Percentage of People with a Regular Health Care Provider

Notes: Bold text shows uninsured persons were statistically significantly different

from insured persons.

* Change from previous survey is statistically significant at p<.05.

# Change from 1997 to 2001 is statistically significant at p<.05.

1 African Americans or Latinos were significantly different from whites in the

same year.

2 African Americans were significantly different from Latinos in the same year.

Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey

Back to Top

Persistent Problems Among Latinos

![]() hile trends for both African Americans and Latinos are

reason for concern, access difficulties among Latinos are

particularly worrisome. Among the uninsured, disparities

in the percentage of Latinos and whites who had a doctor

visit were more than twice the difference between insured

Latinos and whites. In 2001, the difference in having a

physician visit between uninsured Latinos and uninsured

whites was about 18 percentage points. Among insured

Latinos and whites, this difference was about 7 points.

Between 1997 and 2001, uninsured Latinos were consistently

the least likely of any ethnic group to have seen a

physician in the last year.

hile trends for both African Americans and Latinos are

reason for concern, access difficulties among Latinos are

particularly worrisome. Among the uninsured, disparities

in the percentage of Latinos and whites who had a doctor

visit were more than twice the difference between insured

Latinos and whites. In 2001, the difference in having a

physician visit between uninsured Latinos and uninsured

whites was about 18 percentage points. Among insured

Latinos and whites, this difference was about 7 points.

Between 1997 and 2001, uninsured Latinos were consistently

the least likely of any ethnic group to have seen a

physician in the last year.

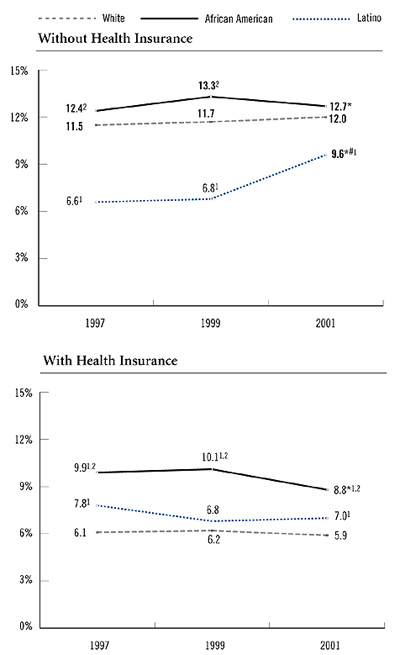

From 1997 to 2001, insured Latinos typically used emergency rooms for care more often than insured whites. Yet, uninsured Latinos used emergency rooms much less frequently than uninsured whites. Uninsured Latinos, however, are increasing the proportion of their outpatient care that occurs in emergency rooms (see Figure 2). In 2001, nearly 10 percent of uninsured Latinos’ visits with health care providers occurred in emergency rooms, up from 6.6 percent in 1997. About 7 percent of insured Latinos’ visits occurred in emergency rooms in 2001, a pattern that has not changed since 1997.

FIGURE 2: Percentage of Visits with Health Care Providers in Emergency Rooms

Notes: Bold text shows uninsured persons were statistically significantly different

from insured persons.

* Change from previous survey is statistically significant at p<.05.

# Change from 1997 to 2001 is statistically significant at p<.05.

1 African Americans or Latinos were significantly different from whites in the

same year.

2 African Americans were significantly different from Latinos in the same year.

Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey

Back to Top

Uninsured Minorities Have Lower Incomes

![]() nalysis of the Household Surveys exploring multiple

factors that contribute to disparities in access to health

care found that lack of insurance was responsible for

the largest portion of disparities in access, followed by

income.4

Hence, financial resources also may contribute

to disparities in access among the uninsured. Minority

Americans without insurance earn less money than

uninsured whites. In 2001, more than half of uninsured

whites had incomes greater than 200 percent of poverty,

or $17,180 annually for a single person. In contrast, only

one-third of uninsured African Americans and about

one-quarter of Latinos had incomes that high. Uninsured

whites’ greater resources may help to explain why they

have fewer problems than do uninsured African

Americans and Latinos.

nalysis of the Household Surveys exploring multiple

factors that contribute to disparities in access to health

care found that lack of insurance was responsible for

the largest portion of disparities in access, followed by

income.4

Hence, financial resources also may contribute

to disparities in access among the uninsured. Minority

Americans without insurance earn less money than

uninsured whites. In 2001, more than half of uninsured

whites had incomes greater than 200 percent of poverty,

or $17,180 annually for a single person. In contrast, only

one-third of uninsured African Americans and about

one-quarter of Latinos had incomes that high. Uninsured

whites’ greater resources may help to explain why they

have fewer problems than do uninsured African

Americans and Latinos.

Back to Top

Coverage Counts Most

![]() or a majority of Americans, health insurance is the key

that unlocks the doors to health care. Decreasing existing

gaps in insurance coverage can aid efforts to reduce disparities

in access to health care.

or a majority of Americans, health insurance is the key

that unlocks the doors to health care. Decreasing existing

gaps in insurance coverage can aid efforts to reduce disparities

in access to health care.

Rapidly rising health care costs may lead to greater numbers of uninsured Americans.5 If disparities remain greater among the uninsured than among the insured populations and coverage declines, closing ethnic and racial access gaps could continue to challenge policy makers. Additional efforts, such as expanding safety net resources in minority communities, may be necessary to eliminate disparities in health care.

Back to Top

Data Sources

![]() his Tracking Report presents findings of the

HSC Community Tracking Study Household

Survey, a nationally representative telephone

survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population

conducted in 1997, 1999 and 2001.

Each round of the survey included interviews

with more than 60,000 persons and 33,000

families. Estimates for the measures were

weighted to represent the U.S. population. All

comparisons and differences described are statistically

significant at p< 0.05.

his Tracking Report presents findings of the

HSC Community Tracking Study Household

Survey, a nationally representative telephone

survey of the civilian, noninstitutionalized population

conducted in 1997, 1999 and 2001.

Each round of the survey included interviews

with more than 60,000 persons and 33,000

families. Estimates for the measures were

weighted to represent the U.S. population. All

comparisons and differences described are statistically

significant at p< 0.05.

Working-age adults age 18 to 64 in three racial or ethnic groups are compared. African American refers to all non-Latino African Americans, and white refers to all non-Latino white Americans.

Back to Top

Notes

Web-Exclusive Data Tables for Tracking Report 2

- Web Table 1

Income, Access to Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance, and Insurance Coverage among African American, Latino and White Persons, 1997-2001 - Web Table 2

Access to care, preventive care, and trust in doctors among African American, Latino, and white persons, 1997-2001 - Web Table 3

Access to care among insured and uninsured African American, Latino, and white persons, 1997-2001 - Web Table 4

Income and Access to Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance among African American, Latino, and white persons, 1997-2001

TRACKING REPORTS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Richard Sorian

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549 (for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261 (for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org