Tax Credits and the Affordability of Individual Health Insurance

Issue Brief No. 53

July 2002

Jack Hadley, James D. Reschovsky

![]() s federal policy makers explore using tax credits to help

uninsured Americans buy individual health insurance, a key question is whether

the credits are large enough to make insurance affordable for those who are

older or in less-than-perfect health. A Center for Studying Health System Change

(HSC) analysis of two leading proposals—one by President Bush and the

other by a bipartisan group of senators—indicates tax credits would make individual

coverage affordable for many people but are unlikely to offer much help to those

who are older or in imperfect health. For example, nine out of 10 19- to 29-year-olds

in excellent health would receive credits covering at least half of the estimated

cost of an individual policy, compared with only one in 100 people age 55-64

in poor health.

s federal policy makers explore using tax credits to help

uninsured Americans buy individual health insurance, a key question is whether

the credits are large enough to make insurance affordable for those who are

older or in less-than-perfect health. A Center for Studying Health System Change

(HSC) analysis of two leading proposals—one by President Bush and the

other by a bipartisan group of senators—indicates tax credits would make individual

coverage affordable for many people but are unlikely to offer much help to those

who are older or in imperfect health. For example, nine out of 10 19- to 29-year-olds

in excellent health would receive credits covering at least half of the estimated

cost of an individual policy, compared with only one in 100 people age 55-64

in poor health.

- Understanding the Individual Insurance Market

- How Far Can Tax Credits Reach?

- Less Help for Those Most in Need

- Policy Implications

- Making Health Insurance More Affordable: Two Tax-Credit Proposals

- Data Source and Methods

- Notes

Understanding the Individual Insurance Market

![]() n 2000-01, slightly more than 30 million people under

the age of 65 were uninsured and did not have access to employer-sponsored insurance.1

Recent proposals seek to encourage people without access to employer-sponsored

insurance and who are ineligible for public insurance programs to buy individual,

or non-group, insurance by offering income-related tax credits to reduce the

cost of insurance (see box). Currently, only 10.3 million

Americans, or 5 percent of the nonelderly insured population, have individual

insurance.

n 2000-01, slightly more than 30 million people under

the age of 65 were uninsured and did not have access to employer-sponsored insurance.1

Recent proposals seek to encourage people without access to employer-sponsored

insurance and who are ineligible for public insurance programs to buy individual,

or non-group, insurance by offering income-related tax credits to reduce the

cost of insurance (see box). Currently, only 10.3 million

Americans, or 5 percent of the nonelderly insured population, have individual

insurance.

A key policy question is whether proposed tax credits are large enough to make individual insurance affordable for older people or people in less- than-perfect health, many of whom are either priced out or shut out of the current individual insurance market. The answer depends on how much it costs to buy individual insurance for those eligible for tax credits. Even large tax credits may be insufficient to make insurance affordable for those facing the highest premiums because of their age or health.2

Determining the cost of individual insurance is complicated because of the prevalence of medical underwriting in the individual market.3 Some argue that people with preexisting medical conditions may be unable to obtain any offers of insurance or, if they do, the price is unaffordable or the coverage excludes care for their conditions.4 Others maintain that actual experience with individual insurance indicates relatively little medical underwriting, that costs are not very sensitive to differences in people’s health conditions and that decisions to purchase coverage are not strongly related to health.5

HSC analyzed the cost of individual insurance using premiums reported by people nationwide in the Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey in 1996-97 and 1998-99 (see Data Source and Methods). Estimated individual insurance premiums for a single person increase with both advancing age and declining health. For example:

- An average individual insurance policy costs a single person age 19-29 who is in excellent health an estimated $121 a month, or $1,452 a year. If that same person is in poor health, the policy will cost $180 a month, or $2,160 a year. 8

- A single person age 55-64 in excellent health would pay about $177 a month, or $2,124 a year. A person 55-64 in poor health would pay $273, or $3,276 a year, a 54 percent difference.

In 1998-99, 6 million uninsured nonelderly adults reported their health as either fair or poor. Another 7.5 million uninsured people in good or excellent health reported having at least one health condition that could lead to higher prices or coverage exclusions in the individual market.

How Far Can Tax Credits Reach?

![]() o analyze the potential impact of proposed

tax credits on the individual market, HSC

identified people likely to qualify for a credit

based on their current insurance coverage

and income.9

An analysis of CTS data suggests

that an estimated 28.6 million people without

access to employer-sponsored or public insurance

would be eligible to receive a credit under

the REACH proposal. Most (88%) of these

people, or 25.2 million, also would receive a

credit under the Bush plan. About 80 percent

of those eligible for a credit under either plan

are uninsured (the remaining 20 percent

already have individual insurance coverage).

o analyze the potential impact of proposed

tax credits on the individual market, HSC

identified people likely to qualify for a credit

based on their current insurance coverage

and income.9

An analysis of CTS data suggests

that an estimated 28.6 million people without

access to employer-sponsored or public insurance

would be eligible to receive a credit under

the REACH proposal. Most (88%) of these

people, or 25.2 million, also would receive a

credit under the Bush plan. About 80 percent

of those eligible for a credit under either plan

are uninsured (the remaining 20 percent

already have individual insurance coverage).

Looking only at the uninsured, the REACH bill would provide a larger average credit per family: $1,535, compared with $1,155 for the Bush plan. Consequently, the REACH proposal would provide a larger average subsidy of the estimated premium for individual insurance: 54 percent, compared with 43 percent for the Bush plan.

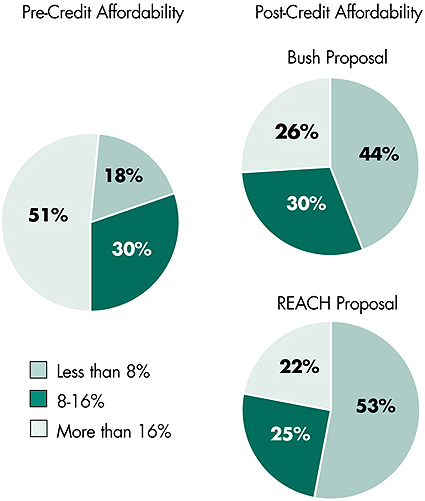

Even if the credit provides a substantial reduction in what consumers pay for insurance, the after-credit premium still needs to be affordable to induce people to purchase coverage. While the relationship among income, price, subsidy percentage and the decision to purchase insurance is complex, a useful yardstick for measuring affordability is the premium as a percentage of family income. Based on CTS data for people who currently own individual insurance policies, about half spend 8 percent or less of their income for coverage, and about three-quarters pay less than 16 percent of their income.

To gauge whether people would be more or less likely to buy coverage with a tax credit, HSC simulated the proportions of people who would be:

- more likely to buy coverage (those who would pay less than 8 percent of family income);

- somewhat more likely to buy coverage (those who would pay between 8 percent and 16 percent); and

- least likely to buy coverage (those who would pay more than 16 percent of family income).

Without a tax credit, uninsured people would spend an average of 25 percent of their income to buy individual coverage. The Bush proposal would drop that average to 16 percent; the REACH plan would lower it further to 14 percent.

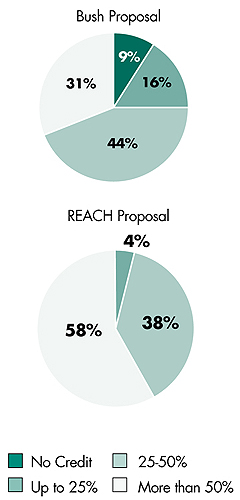

Under both proposals, substantial numbers of people would receive credits covering 50 percent or more of the cost of individual insurance and, as a consequence, would face post-credit insurance costs of less than 8 percent of income. The REACH proposal is more generous. It provides larger subsidies—more than 50 percent of the cost of insurance—to more people and shifts more people into the affordable range, or a post-credit premium of less than 8 percent of income. Under REACH, the tax credit would cover at least half of the cost of individual insurance for 58 percent of uninsured people presumed eligible for a credit, compared with 31 percent of uninsured people under the Bush plan (see Figure 1).

Without tax credits, only 18 percent of uninsured eligibles are estimated to face insurance costs of less than 8 percent of family income, and even with this arguably affordable cost, these people remain uninsured. Both tax credit proposals increase the proportion of uninsured people who would fall into the affordable range: 53 percent under REACH and 44 percent under the Bush proposal, although 22 percent to 26 percent would still face post-credit premiums amounting to more than 16 percent of their incomes plan (see Figure 2).

Figure 1 Distribution by Tax Credit as a Percentage of Premium* * Among uninsured, potentially eligible people. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1996-97 and 1998-99 |

Figure 2 Distribution by Affordability of Individual Insurance (premium as a percentage of family income)* * Among uninsured, potentially eligible people. Note: Total may not add up to 100% due to rounding. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1996-97 and 1998-99 |

Less Help for Those Most in Need

![]() oth proposals would provide significant help to a substantial

number of people. But both are also limited in how much they can help those

who are older, are in poorer health or have very low incomes. Even under the

more generous REACH proposal, only 22 percent of the poorest people would face

post-credit premiums in the affordable range, compared with more than two-thirds

of those with family incomes above poverty. More than four times as many of

the poorest people would still face premiums exceeding 16 percent of their incomes—46

percent of the poorest, compared with 10 to 12 percent of the nonpoor (see

Table 1).

oth proposals would provide significant help to a substantial

number of people. But both are also limited in how much they can help those

who are older, are in poorer health or have very low incomes. Even under the

more generous REACH proposal, only 22 percent of the poorest people would face

post-credit premiums in the affordable range, compared with more than two-thirds

of those with family incomes above poverty. More than four times as many of

the poorest people would still face premiums exceeding 16 percent of their incomes—46

percent of the poorest, compared with 10 to 12 percent of the nonpoor (see

Table 1).

Post-credit premiums also become much less affordable as people’s health worsens or they grow older. Almost two-thirds of people in poor health would still have to pay more than 16 percent of their incomes, compared with only 12 percent of people in excellent health. Similarly, 43 percent of people 55-64 would still find premiums unaffordable, compared with 15 percent of 19- to 29-year-olds.

The combined effects of age and health create wide variations in the degree of assistance tax credits would provide toward purchasing individual coverage. For example:

- Ninety-one percent of people 19-29 in excellent health would receive credits covering at least half of the cost of an individual insurance policy, and three-fourths would spend less than 8 percent of their income to pay their share.

- One-third of people 55-64 who are in excellent health would receive a credit covering at least half of their cost of insurance, but only 10 percent of those in fair health would receive similar assistance.

- Only 1 percent of people 55-64 in poor health would receive credits covering half of the cost of individual insurance.

- Half of older people in fair health and 69 percent of those in poor health still would need to spend more than 16 percent of their income on insurance after the credits.

| Table 1 REACH Proposal: Distribution of People by Post-Credit Affordability of Individual Insurance, by Poverty Status, Health Status and Age* |

||||

|

Premium as a Percent of Family Income

|

Subsidy More Than 50%

|

|||

|

Less Than 8%

|

8-16%

|

More Than 16%

|

||

| Poverty Status | ||||

| Less Than 100% FPL |

22%

|

32%

|

46%

|

55%

|

| 100-200% FPL |

66

|

24

|

10

|

64

|

| More Than 200% FPL |

68

|

20

|

12

|

54

|

| Health Status | ||||

| Excellent |

66

|

22

|

12

|

71

|

| Very Good or Good |

54

|

26

|

20

|

58

|

| Fair |

41

|

28

|

31

|

48

|

| Poor |

18

|

22

|

60

|

24

|

| Age | ||||

| 19-29 |

64

|

21

|

15

|

81

|

| 30-44 |

54

|

27

|

19

|

56

|

| 45-54 |

39

|

27

|

34

|

32

|

| 55-64 |

30

|

27

|

43

|

13

|

| Age and Health Status | ||||

| Age 19-29 in Excellent Health |

76

|

15

|

9

|

91

|

| Age 55-64 in Excellent Health |

29

|

51

|

20

|

33

|

| Age 55-64 in Fair Health |

24

|

26

|

50

|

10

|

| Age 55-64 in Poor Health |

13

|

18

|

69

|

1

|

| * When the Bush proposal is evaluated, similar

distributions result. These are available in web-exclusive tables at www.hschange.org.

Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1996-97 and 1998-99 |

||||

Policy Implications

![]() his analysis suggests that tax credits based

only on income and family size will fail to

help many in greatest need of coverage.

Structuring a tax credit to vary with the

ages of the recipients, as well as with

income and family size, would help uninsured

people in poorer health to purchase

health insurance, because health tends to

decline with age and insurance premiums are

known to vary with age. Basing the size of the

credit on income relative to the poverty line

and providing larger credits than under the

current proposals for those below poverty

could improve affordability for the very poor.

his analysis suggests that tax credits based

only on income and family size will fail to

help many in greatest need of coverage.

Structuring a tax credit to vary with the

ages of the recipients, as well as with

income and family size, would help uninsured

people in poorer health to purchase

health insurance, because health tends to

decline with age and insurance premiums are

known to vary with age. Basing the size of the

credit on income relative to the poverty line

and providing larger credits than under the

current proposals for those below poverty

could improve affordability for the very poor.

Adjusting tax credits for variations in health is a much more complex and challenging task. Roughly 6 million uninsured people are currently in fair or poor health, and another 7.5 million are in good health but have one or more potentially chronic health conditions. Many of these people might not be able to buy an individual insurance policy at any price, so an alternative approach that complements a tax credit may be needed.

One option is to build on the experiences of state high-risk pools, using a decentralized network of administrative offices to screen applicants’ health conditions. 10 The tax credit amount might be increased for people who qualify for high-risk pools, since premiums charged by the pools can be high. 11 If variations in the availability and structure of high-risk pools across states are viewed as inequitable, then a national pool or a joint federal-state approach could be evaluated.

Policy makers also might consider restructuring the individual insurance market. Concerns about potential adverse effects on market structure of regulatory requirements such as guaranteed issue, guaranteed renewal and medical-underwriting restrictions may be alleviated if tax credits expand the size of the individual insurance market by attracting large numbers of relatively healthy people.

Another option is reinsurance of individual policies or after-the-fact compensation of insurers for people who have very large medical expenses. The cost of insurance for these people would be spread over a potentially much larger pool or be publicly funded, depending on the specific mechanism used. For example, New York’s Healthy New York program includes a reinsurance mechanism.12

Finally, many people with very low incomes may be eligible for existing public insurance programs—suggesting that more may need to be done to enroll them. For others, such as adults without children or people in states with very low income-eligibility thresholds for covering otherwise eligible adults, expanding public insurance eligibility or allowing credits to be used to buy into existing public insurance programs might be considered.

Making Health Insurance More Affordable: Two Tax-Credit Proposals

- President Bush’s fiscal year 2003 budget includes an individual insurance tax credit that would provide individuals with incomes under $15,000 with a $1,000 credit that would decrease to zero at an income of $30,000. Families would receive $1,000 per adult and $500 per child, up to a maximum of $3,000 for families with incomes up to $25,000. Families with incomes of $60,000 or more would be ineligible.

- The Relief, Equity, Access and Coverage for Health (REACH) Act of 2001 (S. 590) proposes tax credits for people without access to employer-sponsored insurance of up to $1,000 for individuals with adjusted gross incomes below $35,000 in 2002 and $2,500 for families with incomes below $55,000.7 The tax credit amount would decline as income increases. Individuals with incomes of $45,000 or more and families with incomes of $65,000 or more would be ineligible.

Data Source and Methods

![]() his Issue Brief presents findings

from HSC’s Community Tracking

Study Household Survey conducted

in 1996-97 and 1998-99. That survey

is a nationally representative

telephone survey of the civilian,

noninstitutionalized population,

supplemented by in-person interviews

of households without

telephones to ensure proper representation.

Each round of the survey

contains information on about

60,000 people, and the response

rates ranged from 60 percent to

65 percent.

his Issue Brief presents findings

from HSC’s Community Tracking

Study Household Survey conducted

in 1996-97 and 1998-99. That survey

is a nationally representative

telephone survey of the civilian,

noninstitutionalized population,

supplemented by in-person interviews

of households without

telephones to ensure proper representation.

Each round of the survey

contains information on about

60,000 people, and the response

rates ranged from 60 percent to

65 percent.

The cost of individual insurance calculated for this Issue Brief used premium data from almost 2,500 policies reported by survey respondents. The analysis is based on estimates of the cost of individual insurance projected to the entire population potentially eligible to receive tax credits. The premium estimates are adjusted for the fact that people who actually buy such policies may be in significantly better health than those who do not.6 Without making this adjustment, actual premiums paid by people currently in the individual insurance market are not good indicators of what it would cost other people to buy individual policies.

Notes

| 1. | Population estimates are from CTS Household Surveys. Dollar figures have been inflated to reflect 2002 prices. |

| 2. | Simantov, Elisabeth, Cathy Schoen and Stephanie Bruegman, "Market Failure? Individual Insurance Markets for Older Americans," Health Affairs, Vol. 20, No. 4 (July/August 2001). |

| 3. | Jackson Conwell, Leslie, and Sally Trude, Stand-Alone Health Insurance Tax Credits Aren’t Enough, Issue Brief No. 41, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (July 2001). |

| 4. | Pollitz, Karen, Richard Sorian and Kathy Thomas, How Accessible Is Individual Health Insurance for Consumers in Less-than-Perfect Health? The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (June 2001). |

| 5. | Pauly, Mark, and Bradley Herring, "Expanding Coverage via Tax Credits: Trade-Offs and Outcomes," Health Affairs,Vol. 20, No. 1 (January/February 2001); Saver, Barry G., and Mark P. Doescher, "To Buy or Not to Buy: Factors Associated with the Purchase of Nongroup, Private Health Insurance," Medical Care, Vol. 38, No. 2 (February 2000). |

| 6. | The analysis first examines whether health influences the likelihood that a person will have nongroup insurance and then controls for that effect in estimating the relationship between health and the cost of the policy using a statistical method to adjust for selection bias. See Hadley, Jack, and James Reschovsky, "Health and the Cost of Nongroup Insurance," unpublished working paper, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (July 2002). |

| 7. | REACH also includes provisions for tax credits to subsidize premiums paid by low-income people covered by employer-sponsored insurance to discourage people from dropping unsubsidized employer insurance in favor of subsidized insurance. However, this analysis only considers tax credits for individual insurance. |

| 8. | The estimates for those in fair or poor health may still understate the premiums they would face because the statistical adjustment was based only on self-reported health status, rather than detailed information on specific health conditions or physical limitations that insurance companies would use in medical underwriting. |

| 9. | We defined the eligible population as individuals, families or parts of families that do not have access to employer-sponsored coverage, are not covered by public insurance and have incomes below the maximum incomes specified by the REACH proposal. |

| 10. | Swartz, Katherine, Markets for Individual Health Insurance: Can We Make Them Work with Incentives to Purchase Insurance? The Commonwealth Fund (December 2000); Jackson Conwell, Leslie, and Sally Trude, Stand-alone Health Insurance Tax Credits Aren’t Enough, Issue Brief No. 41, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, DC (July 2001). |

| 11. | Achman, Lori, and Deborah Chollet, Insuring the Uninsurable: An Overview of State High-Risk Health Insurance Pools, The Commonwealth Fund (August 2001). |

| 12. | Swartz, Katherine, and Patricia Seliguer Keenan, Healthy New York: Making Insurance More Affordable for Low-Income Workers, The Commonwealth Fund (November 2001). |

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Richard Sorian

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added

to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549

(for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261

(for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org