Rising Pressure: Hospital Emergency Departments as Barometers of the Health Care System

Issue Brief No. 101

Nov. 18, 2005

Ann S. O'Malley, Anneliese M. Gerland, Hoangmai H. Pham, Robert A. Berenson

Pressures—ranging from persuading specialists to provide on-call coverage to dealing with growing numbers of patients with serious mental illness—are building in already-crowded hospital emergency departments (EDs) across the country, according to findings from the Center for Studying Health System Change’s (HSC) 2005 site visits to 12 nationally representative communities. As the number of ED visits rises significantly faster than population growth, many hospitals are expanding emergency department capacity. At the same time, hospitals face an ongoing nursing shortage, contributing to tight inpatient capacity that in turn hinders admitting ED patients. In their role as hospitals’ “front door” for attracting insured inpatient admissions, emergency departments also increasingly are expected to help hospitals compete for insured patients while still meeting obligations to provide emergency care to all-comers under federal law. Failure to address these growing pressures may compromise access to emergency care for patients and spur already rapidly rising health care costs.

- Emergency Department Pressures Grow

- Many Specialists Unwilling to Provide On-Call Coverage

- Higher ED Use for Primary Care

- Seriously Mentally Ill Patients Strain Crowded EDs

- ED as Hospital Front Door

- Implications

- Notes

- Data Source

Emergency Department Pressures Grow

![]() ospital emergency departments (EDs) provide the stand-ready capacity to respond to life-threatening injuries and illnesses ranging from head traumas to heart attacks. They also serve as the provider of last resort for insured and uninsured patients alike who cannot access care elsewhere. Emergency departments are the one place in the U.S. health system where—under federal law—people can’t be turned away regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay. At the same time, many emergency departments increasingly are expected to help hospitals compete for insured patients with an acute illness or injury.

ospital emergency departments (EDs) provide the stand-ready capacity to respond to life-threatening injuries and illnesses ranging from head traumas to heart attacks. They also serve as the provider of last resort for insured and uninsured patients alike who cannot access care elsewhere. Emergency departments are the one place in the U.S. health system where—under federal law—people can’t be turned away regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay. At the same time, many emergency departments increasingly are expected to help hospitals compete for insured patients with an acute illness or injury.

In the face of these pressures, ED visit rates continue to grow steadily. During the past decade, the number of ED visits nationally rose 26 percent—from 90 million to 114 million in 2003 1—much faster than the 11 percent growth in the U.S. population during the same period.2 And, while the largest proportion of ED visits are made by the privately insured, since 2001, the privately insured ED visit rate decreased 5 percent, while ED visits by Medicaid patients increased 23 percent.3

Many hospitals are expanding and renovating their EDs, in part to attract more insured inpatient admissions, but growing pressures are converging in emergency departments across the country that threaten to compromise care, according to findings from HSC’s 2005 site visits to 12 nationally representative communities (see Data Source). These pressures include:

- Increasing reluctance by specialist physicians to provide emergency department on-call coverage;

- Rising numbers of patients seeking primary care in emergency departments; and

- Growing numbers of patients with serious mental illness going to emergency departments ill-equipped to care for them.

The convergence of these pressures is occurring at the same time that many emergency departments continue to juggle crowded conditions and ambulance diversions as hospitals deal with tight inpatient capacity, which can delay admitted ED patients from getting an inpatient bed. These competing demands are complicating the provision of emergency care with ramifications for patient access and the costs of care.

Back to Top

Many Specialists Unwilling to Provide On-Call Coverage

![]() mergency departments face growing problems in ensuring adequate on-call

specialist physician coverage—a stress that has intensified during the

past two years, according to hospitals in the 12 HSC communities. Under the

federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), all Medicare-participating

hospitals with emergency departments must provide a medical screening exam,

followed by stabilization and further care or transfer as needed, regardless

of the patient’s ability to pay. EMTALA also requires hospitals to maintain

a list of on-call physicians in a manner that best meets the needs of the hospital’s

patients in accordance with the resources available to the hospital. This obligation

does not mandate the provision of broader emergency department services, yet

most hospitals try to offer a wide range of specialty coverage to attract insured

patients and to meet local expectations.

mergency departments face growing problems in ensuring adequate on-call

specialist physician coverage—a stress that has intensified during the

past two years, according to hospitals in the 12 HSC communities. Under the

federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA), all Medicare-participating

hospitals with emergency departments must provide a medical screening exam,

followed by stabilization and further care or transfer as needed, regardless

of the patient’s ability to pay. EMTALA also requires hospitals to maintain

a list of on-call physicians in a manner that best meets the needs of the hospital’s

patients in accordance with the resources available to the hospital. This obligation

does not mandate the provision of broader emergency department services, yet

most hospitals try to offer a wide range of specialty coverage to attract insured

patients and to meet local expectations.

A national survey of emergency department directors confirms that ED patients are facing access problems for emergency specialty care—two-thirds of the directors reported inadequate on-call specialist coverage.4 The top three consequences of inadequate on-call coverage were risk or harm to patients needing specialist care, delay in patient care, and increased ambulance diversions from EDs without adequate specialist on-call coverage.

EMTALA obligations, including ensuring adequate on-call physician coverage, fall predominantly on hospitals, not physicians. Numerous reasons are cited for specialist physicians’ waning interest in taking ED on-call coverage: the perceived higher risk of malpractice litigation, lack of reimbursement for uninsured patients, opportunity costs in terms of time away from their practices and late and unpredictable hours. Historically, emergency on-call coverage has been part of a physician’s obligation in return for hospital admitting privileges. As specialists provide more services in their practices or in freestanding ambulatory facilities and specialty hospitals, they become less dependent on having privileges at general hospitals. This trend potentially diminishes access to specialty care for some patients.

When hospitals have attempted to require staff physicians to take call, some specialists have simply relinquished admitting privileges. EDs report having the most difficulty securing coverage by neurosurgeons, orthopedic surgeons, obstetricians, ophthalmologists, head and neck surgeons, and plastic and hand surgeons.

A 2005 survey of hospital leaders by the American Hospital Association estimated that at least one-third of hospitals have responded by paying additional stipends to certain types of specialists for ED coverage.5 Daily stipends for neurosurgeons to provide on-call coverage average $400 to $1,200, with reports of daily stipends of $2,500 in one community. In addition to these stipends, some hospitals in the 12 HSC communities are paying certain specialist surgeons Medicare rates for care provided to uninsured patients. The challenge of maintaining adequate specialist on-call coverage in EDs through large stipends to specialists will only add pressure to rising health care costs. Citing the high cost of this subsidization, some hospitals are hiring full-time surgical specialists to provide emergency department coverage.

Back to Top

Higher ED Use for Primary Care

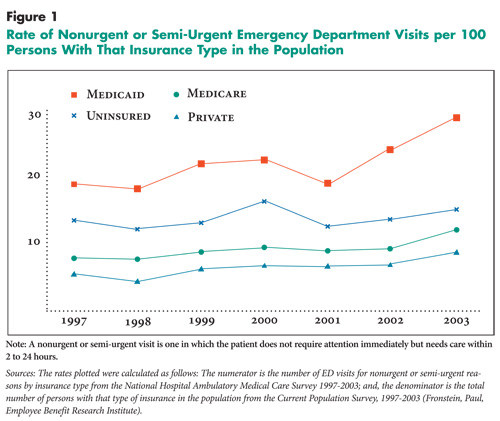

![]() mergency departments, with their 24-hour, seven-day-a-week

stand-ready capacity, are costly sites to provide primary and nonurgent care.6

These facilities are not designed or staffed to provide continuous and comprehensive

primary care efficiently. While the use of emergency departments for primary

care is a long-standing problem, hospital, health plan and public-sector respondents

in the 12 HSC sites reported the problem has intensified during the last two

years. Overall, the percentage of ED visits for nonurgent or semi-urgent reasons

has increased over the past decade. Nationally representative data show a recent

increase in rates of nonurgent and semi-urgent ED visits per 100 persons for

insured and uninsured groups, and especially for Medicaid enrollees (see Figure

1).

mergency departments, with their 24-hour, seven-day-a-week

stand-ready capacity, are costly sites to provide primary and nonurgent care.6

These facilities are not designed or staffed to provide continuous and comprehensive

primary care efficiently. While the use of emergency departments for primary

care is a long-standing problem, hospital, health plan and public-sector respondents

in the 12 HSC sites reported the problem has intensified during the last two

years. Overall, the percentage of ED visits for nonurgent or semi-urgent reasons

has increased over the past decade. Nationally representative data show a recent

increase in rates of nonurgent and semi-urgent ED visits per 100 persons for

insured and uninsured groups, and especially for Medicaid enrollees (see Figure

1).

In many of the 12 HSC communities, respondents believed access to primary care providers was inadequate, especially for Medicaid enrollees and the uninsured. They cited increasing unwillingness among primary care physicians to accept more patients. Public sector and hospital respondents also reported that primary care physicians routinely refer Medicaid and uninsured patients to emergency departments for nonurgent care. Out of frustration with trying to secure specialty care for low-income patients, some primary care physicians also refer patients to the ED in the hope that they will gain access to specialty care.

In response to the rising use of emergency departments for nonurgent or semi-urgent care, some communities are trying novel approaches to improve access to primary care for Medicaid and uninsured patients. In Cleveland, for example, where demands on EDs for primary care have increased dramatically in the last two years, a public-private partnership, funded by the United Way Vision Council, is creating an outreach program to educate residents about primary care services. To improve continuity of care, the group also is developing a shared electronic medical record across three hospital EDs and the area’s three federally qualified community health centers.

A similar effort is being pursued by Seattle’s Harborview Medical Center for frequent ED patients with chronic conditions, such as asthma and diabetes. Using money from the federal Steps to a HealthierUS initiative, Harborview is hiring case managers to connect frequent ED patients with a primary care physician and to train the patients in self-management to help prevent avoidable ED visits.

Back to Top

|

Back to Top

Seriously Mentally Ill Patients Strain Crowded EDs

![]() mergency department directors in the 12 HSC communities,

as well as ED physicians responding to a national survey from The American College

of Emergency Physicians,7 indicate growing numbers of seriously

mentally ill patients are going to emergency departments, creating stress for

staff and hampering ED medical functions. A shortage of inpatient psychiatric

beds results in seriously mentally ill patients being “boarded” in

ED beds until a space can be found for them elsewhere or until they are discharged.

Additional pressures include inadequate numbers of psychiatric practitioners

in many EDs and the perception that seriously mentally ill patients present

a danger to other patients and to staff in general hospital EDs, which may not

be equipped to provide these patients with appropriate supervision and care.

Psychiatric patients’ need for special supervision also affects ED staff

availability for incoming medical emergencies.

mergency department directors in the 12 HSC communities,

as well as ED physicians responding to a national survey from The American College

of Emergency Physicians,7 indicate growing numbers of seriously

mentally ill patients are going to emergency departments, creating stress for

staff and hampering ED medical functions. A shortage of inpatient psychiatric

beds results in seriously mentally ill patients being “boarded” in

ED beds until a space can be found for them elsewhere or until they are discharged.

Additional pressures include inadequate numbers of psychiatric practitioners

in many EDs and the perception that seriously mentally ill patients present

a danger to other patients and to staff in general hospital EDs, which may not

be equipped to provide these patients with appropriate supervision and care.

Psychiatric patients’ need for special supervision also affects ED staff

availability for incoming medical emergencies.

Across the 12 HSC communities, respondents cited recent state budget problems and resulting cuts to state and local mental health departments and Medicaid mental health services, a decline in the number of inpatient psychiatric beds at private and state hospitals in the past decade, and low reimbursement rates for mental health services as the direct causes of rising numbers of seriously mentally ill patients going to general hospital emergency departments.

In response to pressures on EDs from psychiatric patients, some communities have created partnerships between their general hospital systems and mental health centers. In Greenville, S.C., for example, Greenville Mental Health Center, part of the state Department of Mental Health, collaborated with Greenville Hospital System (GHS) to open an emergency department annex specifically for psychiatric patients. Also through this collaboration, several beds at a nearby acute mental health care facility have been designated for referrals from GHS. In exchange, GHS and Greenville Mental Health Center are funding a full-time psychiatrist at this inpatient facility. While this initiative reportedly has helped relieve pressure on the hospital emergency departments, there is concern that it is only a temporary fix for a more systemic problem.

Back to Top

ED as Hospital Front Door

![]() espite success in reducing ambulance diversions via more efficient

management of patient flow from admission to discharge and enhanced emergency

medical services coordination, many hospitals in the 12 communities are expanding

or renovating their EDs. Given the high rates of admission through emergency

departments, having a large or full-service ED is one way to ensure a steady

flow of insured inpatients and make a hospital appealing to clinicians and patients.

espite success in reducing ambulance diversions via more efficient

management of patient flow from admission to discharge and enhanced emergency

medical services coordination, many hospitals in the 12 communities are expanding

or renovating their EDs. Given the high rates of admission through emergency

departments, having a large or full-service ED is one way to ensure a steady

flow of insured inpatients and make a hospital appealing to clinicians and patients.

In general, ED expansions appear to be motivated by competition for well-insured patients, particularly in affluent locations. This was particularly notable in Indianapolis, Miami, northern New Jersey, Phoenix and Seattle. However, even some safety net hospital emergency departments are renovating in part to attract more insured patients. ED directors and hospital CEOs cited changes to architectural appearance and patient flow, increased numbers of beds, decreased waiting times, and greater use of state-of-the-art technology as examples of improvements being made.

Another development at some hospitals, which has improved flow through the ED, is the creation of admissions units adjacent to the ED. Staff transfer patients from the ED to these units as soon as the decision to admit has been made. Once in the admissions unit, the initial set of clinical orders can be carried out, including lab testing, radiology services and drug administration if necessary. In some sites, respondents indicated that these various efforts have already increased rates of insured inpatient admissions.

Continued attention also is being paid to the flow of patients through the hospital. Over the past few years, some hospitals have increased the number of intensive care unit and telemetry beds, resulting in less boarding of patients in the ED. Emergency departments also continue to deal with the consequences of nurse staffing shortages in other parts of the hospital, which has an impact on patient flow through the hospital. Although respondents noted that communities have come together to coordinate ambulance diversions, there is at present no policy mechanism that fosters the coordination of ED expansions around community population-based needs assessment.

Back to Top

Implications

![]() ngoing strategies to improve hospital system efficiency, along with

ED expansions and renovations, have the potential to relieve some of the pressures

in emergency departments. However, these improvements will need to be accompanied

by efforts to address the growing external stresses on emergency departments—namely,

increasing reluctance by specialist physicians to provide ED on-call coverage;

rising numbers of patients seeking primary care in emergency departments; and

growing numbers of seriously mentally ill patients going to emergency departments.

ngoing strategies to improve hospital system efficiency, along with

ED expansions and renovations, have the potential to relieve some of the pressures

in emergency departments. However, these improvements will need to be accompanied

by efforts to address the growing external stresses on emergency departments—namely,

increasing reluctance by specialist physicians to provide ED on-call coverage;

rising numbers of patients seeking primary care in emergency departments; and

growing numbers of seriously mentally ill patients going to emergency departments.

The rising pressure in emergency departments is a result of larger forces throughout the health care system, including financial incentives that reward specialist physicians for performing more procedures in physician-owned ambulatory settings and in specialty hospitals; diminishing access to primary care; declining funding for community-based mental health services; and financial pressures on hospitals to pursue business strategies of seeking higher-paying patients and services. Left unaddressed, these underlying problems can compromise timely access to emergency care for patients and contribute to rising health care costs.

Back to Top

Notes

| 1. | McCaig, Linda F., and Catharine W. Burt, National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2003 Emergency Department Summary, Advance Data from Vital and Health Statistics, No. 358, National Center for Health Statistics, Hyattsville, Md., (2005). |

| 2. | U.S. Census Bureau, http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/hlthins/historic/hihistt1.html. |

| 3. | National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey 1997-2003 at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs. |

| 4. | “On-Call Specialist Coverage in U.S. Emergency Departments, American College of Emergency Physicians Survey of Emergency Department Directors” (September 2004). Executive summary available at http://www.acep.org/NR/rdonlyres/A3D31508-1462-4314-B13E-ED3AECE924F6/0/RWJfinal.pdf. |

| 5. | “Taking the Pulse: The State of America’s Hospitals,” American Hospital Association, survey report available at http://www.ahapolicyforum.org/ahapolicyforum/resources/content/TakingthePulse2005.pdf, last accessed on Nov. 1, 2005. |

| 6. | Bamezai, Anil, Glenn Melnick and Amar Nawathe, “The Cost of an Emergency Department Visit and Its Relationship to Emergency Department Volume,” Annals of Emergency Medicine, Vol. 45, No. 5 (May 2005). |

| 7. | “Emergency Departments See Dramatic Increase in People with Mental Illness - Emergency Physicians Cite State Health Care Budget Cuts as Root of Problem,” American College of Emergency Physicians, news release (April 27, 2004). |

Back to Top

Data Source

Every two years, HSC researchers visit 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities to track changes in local health care markets. The 12 communities are Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis; Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County, Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. In 2005, HSC researchers interviewed hospital executives, hospital associations, policy makers, emergency department and nursing directors, private and public providers and health plans about hospital emergency departments.