Behind the Slow Growth of Employer-Based Consumer-Driven Health Plans

Issue Brief No. 107

December 2006

Jon R. Gabel, Jeremy D. Pickreign, Heidi H. Whitmore

- Do Consumers Want to Direct Their Health Care?

- Many CDHP Enrollees Lack a Choice of Plans

- Where are the Savings?

- When One Plan Type is Offered: CDHP vs. Traditional Plans

- Implications

- Notes

- Data Source

Do Consumers Want to Direct Their Health Care?

![]() n recent years, many benefits consultants, health plan executives and policy makers have asserted that a new generation of health benefits—consumer-directed health plans (CDHPs)—will rise as the past generation—tightly managed care—fades.

n recent years, many benefits consultants, health plan executives and policy makers have asserted that a new generation of health benefits—consumer-directed health plans (CDHPs)—will rise as the past generation—tightly managed care—fades.

A CDHP is typically defined as a high-deductible health plan combined with a tax-advantaged savings account—usually either a health reimbursement arrangement (HRA) or a health savings account (HSA).1 One difference between HRAs and HSAs is their relative portability. HRAs are owned and funded solely by employers, while HSAs are employee-owned and fully portable, meaning workers can retain account balances if they leave their job. Both employees and employers can contribute to HSAs, but employer contributions are optional. For both types of accounts, the plan deductible typically exceeds the employer contribution to the spending account, leaving the employee at risk for higher out-of-pocket costs. To be eligible for an HSA, the person must have a health insurance plan with a specified high deductible, while employers offering HRAs have more flexibility.

The underlying premise of consumer-directed health care is that to help control costs, employees must take more responsibility for their health care decisions. Consumer–directed health care aims to make patients better consumers by providing information about providers and treatments, developing enhanced Internet tools and, perhaps, most importantly, giving patients a greater financial stake in care decisions.

Back to Top

Many CDHP Enrollees Lack a Choice of Plans

![]() f the approximately 70 million American workers who obtain

health benefits from their employer, about 2.7 million, or 4 percent, were enrolled

in a high-deductible health plan with a savings account in 2006, statistically

unchanged from 2.4 million in 2005, according to the 2006 Kaiser Family Foundation/Health

Research and Educational Trust Employer Health Benefits Survey (KFF/HRET) (see

Data Source).2 HSA enrollment grew from

an estimated 800,000 workers in 2005 to 1.4 million in 2006, while HRA enrollment

was statistically unchanged at 1.3 million workers in 2006 from 1.6 million

in 2005. Firms covering 14 percent of insured workers offered a CDHP in 2006.

f the approximately 70 million American workers who obtain

health benefits from their employer, about 2.7 million, or 4 percent, were enrolled

in a high-deductible health plan with a savings account in 2006, statistically

unchanged from 2.4 million in 2005, according to the 2006 Kaiser Family Foundation/Health

Research and Educational Trust Employer Health Benefits Survey (KFF/HRET) (see

Data Source).2 HSA enrollment grew from

an estimated 800,000 workers in 2005 to 1.4 million in 2006, while HRA enrollment

was statistically unchanged at 1.3 million workers in 2006 from 1.6 million

in 2005. Firms covering 14 percent of insured workers offered a CDHP in 2006.

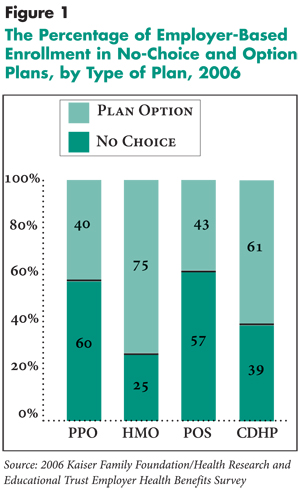

Proponents of CDHPs often contend the plans offer employees greater choice and autonomy in the health care marketplace. Ironically, 39 percent of the 2.7 million people enrolled in employer-sponsored CDHPs had no choice of another type of health plan in 2006 (see Figure 1). The majority of employees enrolled in an HSA-eligible plan (53%) were not offered a choice of plans, while 24 percent of enrollees in HRA plans had no choice of plans.

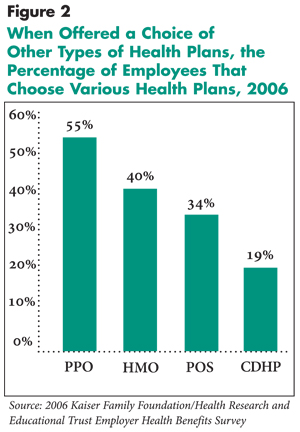

When workers do have a choice of a CDHP and another type of plan, including PPOs, HMOs and point of service (POS) plans, relatively few workers chose a CDHP.3 Of the 8.9 million employees with a choice of a CDHP and at least one other health plan, less than one in five workers (19%) chose a CDHP in 2006, statistically unchanged from 22 percent in 2005 (see Figure 2). In contrast, when PPOs were offered as a choice among other types of plans, 55 percent of employees chose the PPO. The analogous proportions for HMO and POS plans were 40 percent and 34 percent, respectively.

Of the 8.9 million workers with a choice of a CDHP and at least one other type of traditional plan, some workers have a choice of an HRA, an HSA, or in some instances both an HRA and HSA. Of the 3.3 million workers with a choice of an HRA and at least one traditional plan, 28 percent chose an HRA plan, while 12 percent of the 5.6 million workers with a choice of an HSA plan and at least one traditional plan chose an HSA plan.

In terms of exposure to higher out-of-pocket costs, HMOs are the polar opposite of CDHPs. When offered alongside an HMO plan, CDHP enrollment on average was nine percentage points less (not shown) than when HMOs were not offered. This lower enrollment in CDHPs occurred whether the employer was offering an HRA or HSA plan.

Back to Top

|

Back to Top

|

Back to Top

Where are the Savings?

![]() ow CDHPs perform in terms of cost to employers and employees

and financial protection for employees will greatly determine their success

in the health insurance marketplace. When workers have a choice of plans, average

monthly premiums for CDHPs for single coverage ($299) were significantly lower

than for other plan types—PPO plans were the most expensive at $364 (see

Table 1). When employer contributions to the savings accounts

are added to the monthly premium, however, CDHPs and traditional plans did not

differ statistically in cost.

ow CDHPs perform in terms of cost to employers and employees

and financial protection for employees will greatly determine their success

in the health insurance marketplace. When workers have a choice of plans, average

monthly premiums for CDHPs for single coverage ($299) were significantly lower

than for other plan types—PPO plans were the most expensive at $364 (see

Table 1). When employer contributions to the savings accounts

are added to the monthly premium, however, CDHPs and traditional plans did not

differ statistically in cost.

Likewise, workers’ average monthly premium contribution for single coverage in CDHPs ($56) was not statistically different from employee contributions for traditional HMO, PPO and POS plans. Similarly, among CDHPs, HMO, PPO and POS plans, the percentage of the total premium contributed by employees for single coverage was not statistically different.

However, employee cost sharing is significantly greater in CDHPs than in traditional plans. In 2006, the average annual in-network deductible in CDHPs—when offered as choice to workers—was $1,459 for single coverage, considerably greater than for HMO plans ($30), PPO plans ($261) and POS plans ($94). Moreover, CDHPs largely use coinsurance for physician office visits (only 15% of people were enrolled in a CDHP plan using copayments for office visits), while traditional plans overwhelmingly rely on copayments for office visits. With copayments, employees pay a fixed amount for a physician office visit. With coinsurance, employees pay a percentage of the total negotiated bill. Seventy-nine percent of workers in PPOs were enrolled in plans that use copayments for physician office visits, as were 95 percent and 98 percent of workers in HMO and POS plans. Moreover, many employer plans with copayments for office visits waive the employees’ requirement to satisfy the deductible and provide first-dollar coverage for preventive care.4

Back to Top

Table 1

|

||||||||

|

|

CDHP

|

Traditional Plans

|

||||||

|

HMO

|

PPO

|

POS

|

||||||

|

(n=160)

|

(n=525)

|

(n=643)

|

(n=241)

|

|||||

| Monthly Premium, Single Coverage |

$299

|

$339*

|

$364*

|

$363*

|

||||

| Monthly Employer Contribution, Single Coverage |

$243

|

$288*

|

$303*

|

$307*

|

||||

| Monthly Employee Contribution, Single Coverage |

$56

|

$51

|

$61

|

$56

|

||||

| Average Single Deductible, In-Network |

$1,459

|

$30*

|

$261*

|

$94*

|

||||

| Percent of Employees Enrolled in a Plan with Copayments for Office Visits |

15%

|

95%*

|

79%*

|

98%*

|

||||

| Average Monthly Employer Contribution to Savings Account |

$54

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

||||

| Total Employer Contribution (Premium Plus Savings Account) |

$297

|

$288

|

$303

|

$307

|

||||

| * Difference from CDHP and comparison plan

is statistically significantly at p<.01. Note: In a copayment plan, employees pay a fixed amount for each physician office visit. In a coinsurance plan, after the deductible is met, employees pay a percentage of the insurer’s allowed charges for the office visit. Source: 2006 Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research and Educational Trust Employer Health Benefits Survey |

||||||||

Back to Top

When One Plan Type is Offered: CDHP vs. Traditional Plans

![]() ather than offering employees multiple plans, some employers,

particularly firms with fewer than 200 workers, offer only one health plan.

With regard to the cost to employers, total monthly contributions for single

coverage are significantly lower for CDHPs at $226 when only one plan is offered,

as opposed to $288, $319 and $285, respectively, for HMO, PPO and POS plans

(see Table 2). When average monthly employer contributions

($74) to the savings account are added to CDHP premiums, however, differences

among CDHP, HMO, PPO and POS plan costs are not statistically significant.

ather than offering employees multiple plans, some employers,

particularly firms with fewer than 200 workers, offer only one health plan.

With regard to the cost to employers, total monthly contributions for single

coverage are significantly lower for CDHPs at $226 when only one plan is offered,

as opposed to $288, $319 and $285, respectively, for HMO, PPO and POS plans

(see Table 2). When average monthly employer contributions

($74) to the savings account are added to CDHP premiums, however, differences

among CDHP, HMO, PPO and POS plan costs are not statistically significant.

Regarding cost and financial protection for employees, in situations where only one plan is offered there were no statistically significant differences in employees’ monthly premium contributions for single coverage between CDHPs and other plans. But deductibles in CDHPs were more than five times greater than in PPO plans and more than 20 times greater than in HMO plans. Moreover, when CDHPs were offered as the only plan, use of coinsurance for physician office visits was prevalent.

Back to Top

Table 2

|

||||||||

|

|

CDHP

|

Traditional Plans

|

||||||

|

HMO

|

PPO

|

POS

|

||||||

|

(n=38)

|

(n=116)

|

(n=783)

|

(n=178)

|

|||||

| Monthly Premium, Single Coverage |

$260

|

$332*

|

$367*

|

$336*

|

||||

| Monthly Employer Contribution, Single Coverage |

$226

|

$288#

|

$319*

|

$285#

|

||||

| Monthly Employee Contribution, Single Coverage |

$34

|

$44

|

$48

|

$51

|

||||

| Average Single Deductible, In-Network |

$2,112

|

$77*

|

$372*

|

$236*

|

||||

| Percent of Employees Enrolled in a Plan with Copayments for Office Visits |

10%

|

96%*

|

80%*

|

99%*

|

||||

| Average Monthly Employer Contribution to Savings Account |

$74

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

n/a

|

||||

| Total Employer Contribution (Premium Plus Savings Account) |

$300

|

$288

|

$319

|

$285

|

||||

| * Difference from CDHP and comparison plan

is statistically significantly at p<.01. * Difference from CDHP and comparison plan is statistically significantly at p<.05. Note: In a copayment plan, employees pay a fixed amount for each physician office visit. In a coinsurance plan, after the deductible is met, employees pay a percentage of the insurer’s allowed charges for the office visit. Source: 2006 Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research and Educational Trust Employer Health Benefits Survey |

||||||||

Back to Top

Implications

![]() hen offered a choice of plans, relatively few employees

(19%) select CDHPs. This is a major reason why CDHP enrollment has not accelerated

rapidly in the group insurance market. In comparison, based on a member survey,

the industry trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans estimates that 23

percent of all new polices in the individual market were HSA-eligible plans.5

To date, enrollment in employer-based CDHPs has grown more slowly than the early

pace for PPO plans, where PPO market share grew from less than 1 percent in

1984 to 11 percent in 1987.6

hen offered a choice of plans, relatively few employees

(19%) select CDHPs. This is a major reason why CDHP enrollment has not accelerated

rapidly in the group insurance market. In comparison, based on a member survey,

the industry trade group America’s Health Insurance Plans estimates that 23

percent of all new polices in the individual market were HSA-eligible plans.5

To date, enrollment in employer-based CDHPs has grown more slowly than the early

pace for PPO plans, where PPO market share grew from less than 1 percent in

1984 to 11 percent in 1987.6

Analyzing the performance of CDHPs compared with traditional plans provides some basis for understanding why enrollments in general and selection rates in particular are not greater. From the employer’s vantage point, the total cost of CDHP coverage—regardless of whether the employer offers workers a choice of plans—is similar to that for traditional plans. While CDHP premiums are substantially lower, the sum of employers’ contributions to the savings account (if any) and the premium is equivalent to spending on other types of plans.7

From the employee’s vantage point, monthly employee contributions are similar between traditional plans and CDHPs, but employee cost sharing is much higher in CDHPs. Not only are average annual deductibles more than a thousand dollars more than in PPO plans—the traditional plans with the highest deductible—but CDHPs also typically use coinsurance for physician office visits while traditional plans primarily rely on copayments.

On the other hand, if an employee does not expect to use many health care services, higher cost sharing is not so serious a consideration, and the employer’s contribution to the savings account makes a CDHP a savings vehicle.

Lacking historical experience, health plans and employers initially may have priced CDHPs too high, which may explain why the cost of coverage to employers is not different between CDHPs and traditional plans. To guard against favorable selection—where healthier-than-average people enroll—employers also may have set similar monthly contributions for employees in CDHPs and traditional plans. If plans and employers did overprice CDHPs, then subsequent increases in premiums in the next few years are likely to be more modest in CDHPs than traditional plans, thereby increasing the appeal of CDHPs.

In the employer-based market CDHP enrollment may ultimately take off in a manner similar to the early experience of PPOs. For the moment, however, CDHPs have gained only a toehold in the employer-based market, and health plans appear to be more enthusiastic about consumer-directed health care than are employers, who in turn are more enthusiastic than employees.

Back to Top

Notes

Back to Top

Data Source

Study data are from the public use file of the 2006 Kaiser Family Foundation/Health Research and Educational Trust (KFF/HRET) Employer Health Benefits Survey. Survey respondents are employee benefit managers who are asked in a telephone survey a series of questions about their largest HMO, PPO, POS and CDHP. The 2006 survey entailed a sample of 2,122 randomly chosen private and nonfederal public firms with three or more workers. The survey response rate was 48 percent. In the 2006 survey, 205 firms offered a CDHP (72 HRAs and 133 HSAs) of which 38 offered no choice of plans. The sample also includes 783 PPO, 116 HMO, and 178 POS plans that were no-choice products. The KFF/HRET survey uses a series of weights to extrapolate results for the typical employee and firm. Data presented in this Issue Brief are employee-weighted data.

The survey questionnaire asks a series of questions about the provisions of the largest HMO, PPO, POS and high-deductible plan with a savings option (either an HRA or an HSA). HRA and HSA plans are defined as health plans with high deductibles (at least $1,000 for single coverage and $2,000 for family coverage) that are offered with an HRA or are eligible to be offered with a health savings account. For more details about the 2006 Kaiser/HRET Employer Health Benefits Survey see http://www.kff.org/insurance/employer.cfm.

A possible limitation to the KFF/HRET survey for this analysis is the calculation of the percentage of employees that chose a CDHP. The unit of analysis for the survey is the firm rather than the local establishment. It is possible that the CDHP was not available at all establishments within a firm, just as the firm may not offer a traditional plan, particularly an HMO, at all of its establishments. This limitation does not appear to be serious, however. To investigate this, for all firms offering a CDHP as a choice, the CDHP take up rate was regressed on firm size and whether the firm had one or multiple establishments. Larger firms had lower take up, and there was no statistically significant difference between the single- and multi-establishment firms.