Physicians Moving to Mid-Sized, Single-Specialty Practices

Tracking Report No. 18

August 2007

Allison Liebhaber, Joy M. Grossman

The proportion of physicians in solo and two-physician practices decreased significantly from 40.7 percent to 32.5 percent between 1996-97 and 2004-05, according to a national study from the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC). At the same time, the proportion of physicians with an ownership stake in their practice declined from 61.6 percent to 54.4 percent as more physicians opted for employment. Both the trends away from solo and two-physician practices and toward employment were more pronounced for specialists and for older physicians. Physicians increasingly are practicing in mid-sized, single-specialty groups of six to 50 physicians. Despite the shift away from the smallest practices, physicians are not moving to large, multispecialty practices, the organizational model that may be best able to support care coordination, quality improvement and reporting activities, and investments in health information technology.

- Solo and Two-Physician Practices Decline

- Practice Trends Reflect Changing Incentives

- Trends Vary by Specialty

- Changes Greater Among Older Physicians

- Policy Implications

- Notes

- Data Source

- Supplementary Table

Solo and Two-Physician Practices Decline

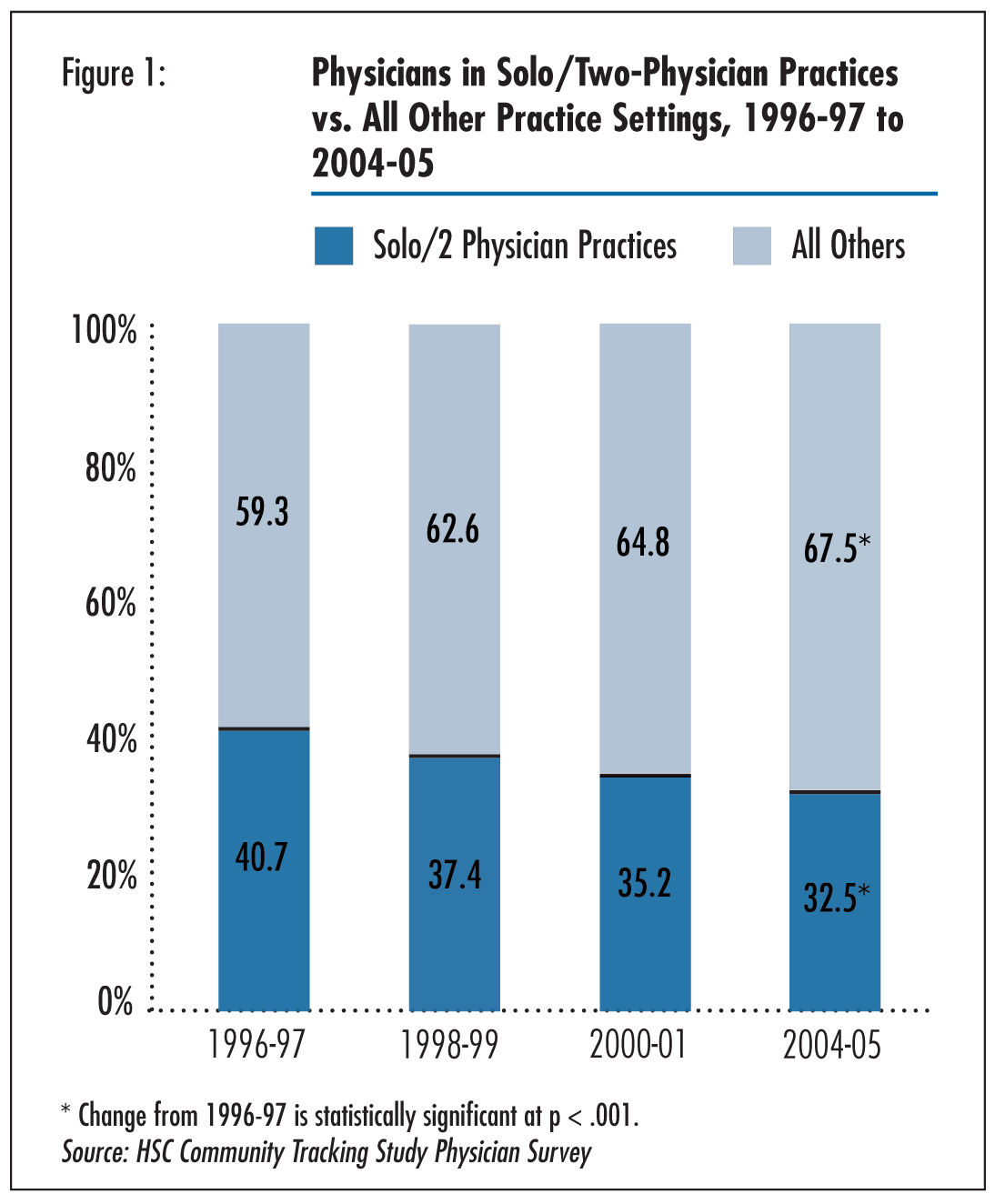

![]() hanges in physician practice settings and organization have important implications for the practice of medicine and the care patients receive. Some experts believe that large, multispecialty practices, which combine primary care physicians and a range of specialists in the same practice, are the organizational structure with the greatest potential to provide consistently high-quality care.1 Indeed, the federal government has targeted some of these practices for quality improvement activities.2 Despite various clinical advantages of multispeciality practice, this organizational structure has declined as more physicians gravitate toward single-specialty practice. The proportion of physicians in multispecialty practices decreased from 30.9 percent to 27.5 percent between 1998-99 and 2004-053 (data not shown), according to HSC’s nationally representative Community Tracking Study (CTS) Physician Survey (see Data Source). While growth of multispecialty practices stalled, other significant changes in physician practice settings and organization took place over the last decade as more physicians have moved to larger practices and forgone an ownership stake in their practices. Although solo and two-physician practices were still the most common practice setting in the United States in 2004-05, the percentage of physicians in solo or two-physician practices decreased from 40.7 percent in 1996-97 to 32.5 percent in 2004-05 (see Figure 1). Likewise, the proportion of physicians in three- to five-physician practices decreased from 12.2 percent to 9.8 percent (see Table 1).

hanges in physician practice settings and organization have important implications for the practice of medicine and the care patients receive. Some experts believe that large, multispecialty practices, which combine primary care physicians and a range of specialists in the same practice, are the organizational structure with the greatest potential to provide consistently high-quality care.1 Indeed, the federal government has targeted some of these practices for quality improvement activities.2 Despite various clinical advantages of multispeciality practice, this organizational structure has declined as more physicians gravitate toward single-specialty practice. The proportion of physicians in multispecialty practices decreased from 30.9 percent to 27.5 percent between 1998-99 and 2004-053 (data not shown), according to HSC’s nationally representative Community Tracking Study (CTS) Physician Survey (see Data Source). While growth of multispecialty practices stalled, other significant changes in physician practice settings and organization took place over the last decade as more physicians have moved to larger practices and forgone an ownership stake in their practices. Although solo and two-physician practices were still the most common practice setting in the United States in 2004-05, the percentage of physicians in solo or two-physician practices decreased from 40.7 percent in 1996-97 to 32.5 percent in 2004-05 (see Figure 1). Likewise, the proportion of physicians in three- to five-physician practices decreased from 12.2 percent to 9.8 percent (see Table 1).

As physicians moved into larger practices, the proportion in groups of six to 50 physicians increased from 13.1 percent to 17.6 percent between 1996-97 and 2004-05.4 Smaller increases were seen in the proportion of physicians in practices with more than 50 physicians and in practices affiliated with medical schools.

Trends in physician ownership over the period mirrored those in practice type. As physicians moved out of the smallest practices, the percentage of physicians who were full or part owners of their practice declined from 61.6 percent to 54.4 percent (see Table 2).

Click here to view this figure as a PowerPoint slide.

Table 1

|

|

1996-97

|

1998-99

|

2000-01

|

2004-05

|

|

| Solo/2-Physician Practices |

40.7%

|

37.4%

|

35.2%

|

32.5%*

|

| 3-5 Physician Practices |

12.2

|

9.6

|

11.7

|

9.8*

|

| 6-50 Physician Practices |

13.1

|

14.2

|

15.8

|

17.6*

|

| >50 Physician Practices |

2.9

|

3.5

|

2.7

|

4.2*

|

| Medical School |

7.3

|

7.7

|

8.4

|

9.3*

|

| HMO |

5.0

|

4.6

|

3.8

|

4.5

|

| Hospital1 |

10.7

|

12.6

|

12.0

|

12.0

|

| Other2 |

8.3

|

10.5

|

10.4

|

10.1*

|

|

* Change from 1996-97 is statistically significant at p<.05. |

||||

Click here to view this table as a PowerPoint slide.

Table 2

|

|

1996-97

|

1998-99

|

2000-01

|

2004-05

|

|

| All Physicians |

61.6%

|

56.7%

|

55.9%

|

54.4%*

|

| Primary Care |

54.3

|

49.6

|

50.1

|

51.8

|

| Medical Specialists |

58.1

|

51.8

|

51.7

|

47.3*

|

| Surgical Specialists |

75.5

|

72.7

|

71.2

|

68.4*

|

|

* Change from 1996-97 is statistically significant at p<.05. |

||||

Click here to view this table as a PowerPoint slide.

Practice Trends Reflect Changing Incentives

![]() rends in physician practice setting and ownership likely reflect changes in physician financial incentives over the past decade and are consistent with HSC site-visit findings about changes in physician practice arrangements.5 Before the first round of the CTS Physician Survey in 1996-97, the rise of tightly managed care was expected to fuel widespread development of large, multispecialty groups, including primary care specialties, to manage risk-sharing arrangements and specialty referrals, while gaining leverage with health plans. Physician practice acquisition by health maintenance organizations (HMOs), hospitals and physician practice management companies was also expected to accelerate.

rends in physician practice setting and ownership likely reflect changes in physician financial incentives over the past decade and are consistent with HSC site-visit findings about changes in physician practice arrangements.5 Before the first round of the CTS Physician Survey in 1996-97, the rise of tightly managed care was expected to fuel widespread development of large, multispecialty groups, including primary care specialties, to manage risk-sharing arrangements and specialty referrals, while gaining leverage with health plans. Physician practice acquisition by health maintenance organizations (HMOs), hospitals and physician practice management companies was also expected to accelerate.

However, by the second round of the CTS Physician Survey in 1998-99, it was evident tightly managed care was not growing as expected, and many large physician practices were in financial trouble. By the third survey in 2000-01, tightly managed care was in full retreat. Multispecialty group creation ceased, and third parties were no longer acquiring physician practices at a rapid pace. Even with managed care in retreat, physicians faced continuing downward pressures on income with practice expenses growing more rapidly than reimbursement rates.6

Increasing financial pressures provided incentives for physicians to aggregate into mid-sized practices to gain economies of scale by spreading fixed costs over a larger number of physicians. Moreover, in a fee-for-service reimbursement environment, in contrast to under risk-sharing arrangements, physicians had incentives to provide profitable procedures and ancillary services, such as high-end imaging and diagnostic testing. Procedure- and service-intensive specialties likely had more opportunities to benefit than other specialists and primary care physicians. Payment for these services is typically higher than for office visits, and the growing trend of physician-owned outpatient facilities provided opportunities for additional physician revenue. In this environment, physicians benefited from aggregating into larger, single-specialty practices with greater capital and scale economies to invest in equipment and facilities to provide these services. Single-specialty groups became more attractive because specialists could reap the advantages of a group practice without having to redistribute income to primary care physicians—traditionally the procedure in multispecialty groups. Single-specialty groups also had opportunities to gain negotiating leverage with health plans while the referral advantage provided by multispecialty groups waned as health plans eased referral restrictions.7

Back to Top

Trends Vary by Specialty

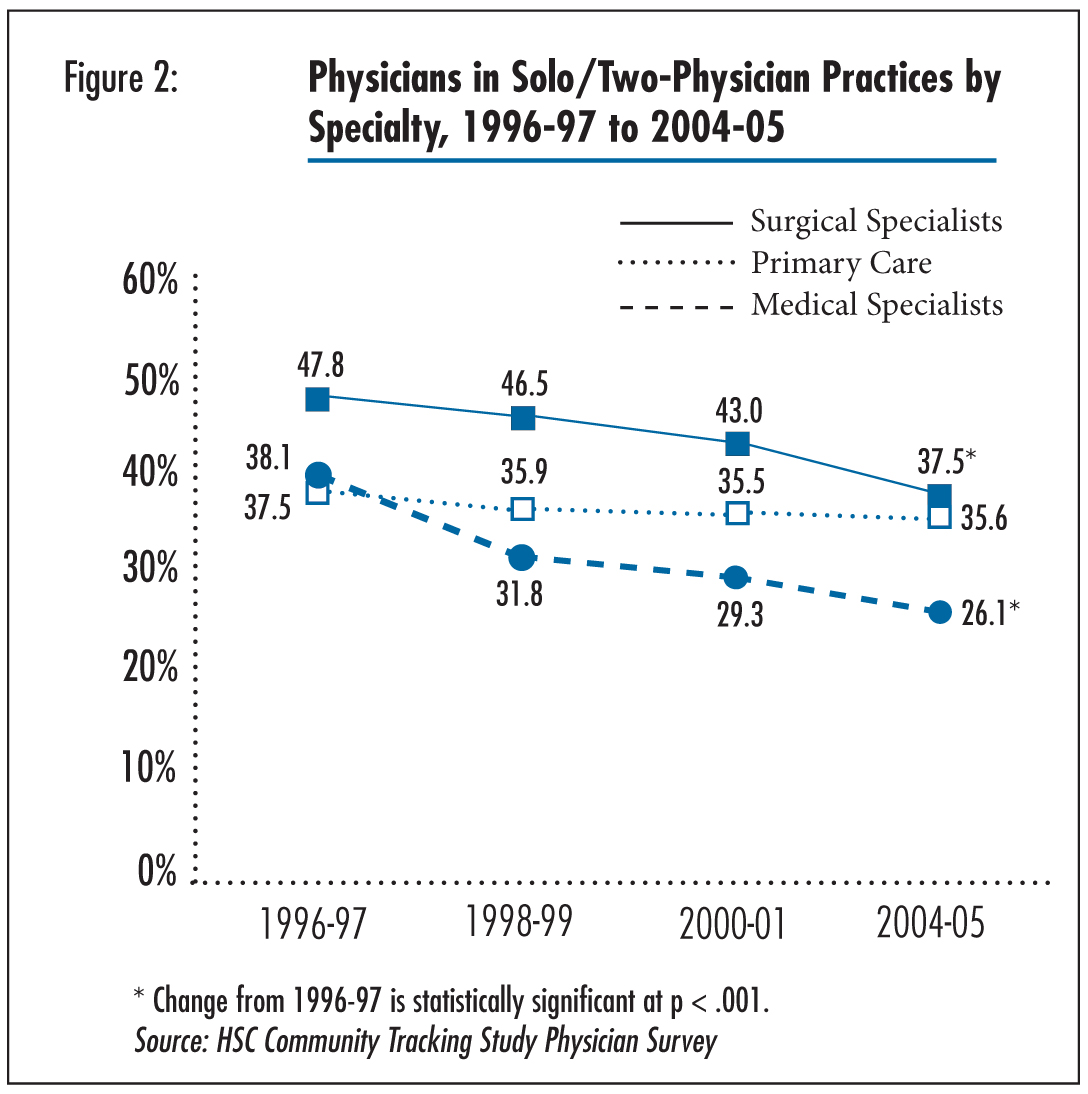

![]() etween 1996-97 and 2004-05, there was a 12.0 percentage point decrease in medical specialists and a 10.3 percentage point decrease in surgical specialists in solo and two-physician practices (see Figure 2). In contrast, the proportion of primary care physicians in solo and two-physician practices remained stable at about 36 percent between 1996-97 and 2004-05. Reflecting the larger decline in solo and two-physician practices, there was a much larger decrease in the percentage of owners among medical specialists and surgical specialists than among primary care physicians. Increased consolidation and decline in ownership among specialists continued throughout 1996-97 to 2004-05.

etween 1996-97 and 2004-05, there was a 12.0 percentage point decrease in medical specialists and a 10.3 percentage point decrease in surgical specialists in solo and two-physician practices (see Figure 2). In contrast, the proportion of primary care physicians in solo and two-physician practices remained stable at about 36 percent between 1996-97 and 2004-05. Reflecting the larger decline in solo and two-physician practices, there was a much larger decrease in the percentage of owners among medical specialists and surgical specialists than among primary care physicians. Increased consolidation and decline in ownership among specialists continued throughout 1996-97 to 2004-05.

Even though the movement of specialists out of solo and two-physician practices contrasts with primary care physicians, all three categories of physicians showed increases in practices with six or more physicians (see Supplementary Table 1). The most striking difference between primary care physicians and specialists was the increased movement of specialists to other practice settings, including medical school faculty practices, hospitals, and hospital-owned, office-based practices. The renewed interest on the part of hospitals and academic medical centers in expanding specialty services during the same period may have made it attractive for them to hire greater numbers of specialists.

Although in the aggregate there is not much difference between primary care physicians and specialists in their consolidation into larger practices, when examined by subspecialty, it does appear that certain medical subspecialties, such as oncology, are moving to larger practices more than others. Other medical subspecialties such as gastroenterology and pulmonology, as well as all the surgical subspecialties examined, showed trends in this direction, but changes were not statistically significant, probably because of small sample sizes. These subspecialties showed decreases in ownership as well (data not shown). Some subspecialists may have more motivation to form larger practices since they have more opportunities to provide profitable procedures and diagnostic services in outpatient settings. The size of practices formed within the six-50 physician range may differ by subspecialty depending on the economies of scale related to the clinical services they provide and amount of local market competition within the subspecialty. Certain subspecialties did appear to aggregate into different size practices within that range, but small sample sizes prevented further examination of these trends. Other subspecialties have less to gain from forming mid-sized groups in terms of economies of scale or leverage. For example, dermatology is the only subspecialty where a majority (61.6 %) of physicians remained in solo and two-physician practices in 2004-05.

Back to Top

Click here to view this figure as a PowerPoint slide.

Changes Greater Among Older Physicians

![]() hile younger physicians were more likely than older physicians to be in larger groups and to be non-owners, the gap narrowed between 1996-97 and 2004-05. Physicians 51 and older saw a 12.7 percentage point decrease in solo and two-physician practices between 1996-97 and 2004-05, from 51.5 percent to 38.8 percent. Physicians 40 and younger only experienced a 3.5 percentage point decrease from 28.3 percent to 24.8 percent, perhaps because there were so few in solo and two-physician practices at the start of the period. Most of the movement for physicians in the 40 and younger and 41 to 50 age ranges occurred between 1996-97 and 1998-99, while the trend for physicians older than 50 continued throughout the decade. The ownership trends mirrored the trends in practice type for each age group (data not shown).

hile younger physicians were more likely than older physicians to be in larger groups and to be non-owners, the gap narrowed between 1996-97 and 2004-05. Physicians 51 and older saw a 12.7 percentage point decrease in solo and two-physician practices between 1996-97 and 2004-05, from 51.5 percent to 38.8 percent. Physicians 40 and younger only experienced a 3.5 percentage point decrease from 28.3 percent to 24.8 percent, perhaps because there were so few in solo and two-physician practices at the start of the period. Most of the movement for physicians in the 40 and younger and 41 to 50 age ranges occurred between 1996-97 and 1998-99, while the trend for physicians older than 50 continued throughout the decade. The ownership trends mirrored the trends in practice type for each age group (data not shown).

Back to Top

Policy Implications

![]() s momentum for pay-for-performance initiatives and information technology (IT) adoption mounts, policy makers envision physicians aggregating into large and, preferably, multispecialty practices. Larger practices are more likely to have the financial and administrative resources to collect quality data, implement quality improvement and reporting activities, and implement information technology, while multispecialty practices are better positioned to enhance care coordination. Large practices also may have more employed physicians and more structured physician leadership, which may make it easier to implement these types of activities. Despite these advantages, the vision of

a growth in large, multispecialty practices so far is at odds with the actual trends.

s momentum for pay-for-performance initiatives and information technology (IT) adoption mounts, policy makers envision physicians aggregating into large and, preferably, multispecialty practices. Larger practices are more likely to have the financial and administrative resources to collect quality data, implement quality improvement and reporting activities, and implement information technology, while multispecialty practices are better positioned to enhance care coordination. Large practices also may have more employed physicians and more structured physician leadership, which may make it easier to implement these types of activities. Despite these advantages, the vision of

a growth in large, multispecialty practices so far is at odds with the actual trends.

Most of the growth so far has been in mid-sized practices, which, although they may be better equipped than solo and two-physician practices, do not yet approach the capabilities envisioned by quality improvement leaders. Moreover, increased consolidation in single-specialty practices raises the potential in some markets that certain specialties can drive up prices in negotiation with health plans. Some market observers also are concerned that if physicians are aggregating into larger practices to provide profitable procedures and ancillary services, the greater ability of physicians to legally self-refer patients under exceptions to self-referral laws could lead to overuse of certain services, further driving up costs of care. At the same time, some benefits to society may be lost from the movement out of smaller practices and away from practice ownership. For example, other HSC research shows that physicians in smaller practices with an ownership stake are substantially more likely to provide charity care than physicians in larger practices or non-owners.8

If physician quality and IT-related payment incentives become more widespread, many are predicting physicians will once again move toward the type of large, multispecialty groups that grew during the height of managed care. However, that trend has not yet materialized. Based on the way physicians are organizing, it appears that the health care system presently does not provide sufficient incentives for physicians to reconsider such practice arrangements. In the current system the opportunities to decrease practice expenses and, especially for specialists, to enhance revenues from profitable services may more strongly influence physician organization than potential opportunities to improve the quality of care.

Back to Top

Notes

| 1. | Crosson, Francis J., “The Delivery System Matters,” Health Affairs, Vol. 24, No. 6 (November/December 2005). |

| 2. | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Medicare Physician Group Practice Demonstration (July 2007). |

| 3. | Data on single or multispecialty practice type were not collected during the 1996-97 CTS Physician Survey. Information on single specialty vs. multispecialty practice type is available only for physician-owned groups and not hospital-owned physician practices. |

| 4. | Estimates for practice sizes reflect only physician-owned practices, not hospital-owned practices. |

| 5. | Casalino, Lawrence P., et al., “Benefits and Barriers to Large Group Medical Practice in the United States,” Archives of Internal Medicine, Vol. 163, No. 16 (September 2003). |

| 6. | Tu, Ha T., and Paul B. Ginsburg, Losing Ground: Physician Income, 1995-2003, Tracking Report No. 15, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (June 2006). |

| 7. | Casalino, Lawrence P., et al., “Growth of Single-Specialty Medical Groups,” Health Affairs, Vol. 23, No. 2 (March/April 2004). |

| 8. | Cunningham, Peter J. and Jessica H. May, A Growing Hole in the Safety Net: Physician Charity Care Declines Again, Tracking Report No. 13, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (March 2006). |

Back to Top

Data Source

This Tracking Report presents findings from the HSC Community Tracking Study Physician Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey of physicians involved in direct patient care in the continental United States conducted in 1996-97, 1998-99, 2000-01 and 2004-2005. The sample of physicians was drawn from the American Medical Association and the American Osteopathic Association master files and included active, nonfederal, office- and hospital-based physicians who spent at least 20 hours a week in direct patient care. Residents and fellows were excluded. The 1996-97, 1998-99 and 2000-01 surveys each contain information on about 12,000 physicians, while the 2004-05 survey includes responses from more than 6,600 physicians. The response rates ranged from 52 percent to 65 percent. More detailed information on survey methodology can be found at www.hschange.org.

Back to Top

Supplementary Table

Supplementary Table 1: Physicians by Subspecialty

and Practice Settings, 1996-97 and 2004-05

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org