Community Health Centers Tackle Rising Demands and Expectations

Issue Brief No. 116

December 2007

Robert E. Hurley, Laurie E. Felland, Johanna Lauer

As key providers of preventive and primary care for underserved people,

including the uninsured, community health centers (CHCs) are the backbone of

the U.S. health care safety net. Despite significant federal funding increases,

community health centers are struggling to meet rising demand for care, particularly

for specialty medical, dental and mental health services, according to findings

from the Center for Studying Health System Change’s (HSC) 2007 site visits

to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities. Health centers are

responding to these pressures by expanding capacity and adding services but

confront staffing, resource and other constraints. At the same time, CHCs are

facing other demands, including increased quality reporting expectations, addressing

racial and ethnic disparities, developing electronic medical records, and preparing

for public health emergencies.

- Community Health Centers Strive to Meet Demand

- More Patients

- Fewer Care Alternatives

- Recruiting and Retaining Staff

- Increased Emphasis on Accountability, Disparities and Public Health

- CHCs Respond to Mounting Challenges

- Future Risks and Opportunities

- Notes

- Data Source

Community Health Centers Strive to Meet Demand

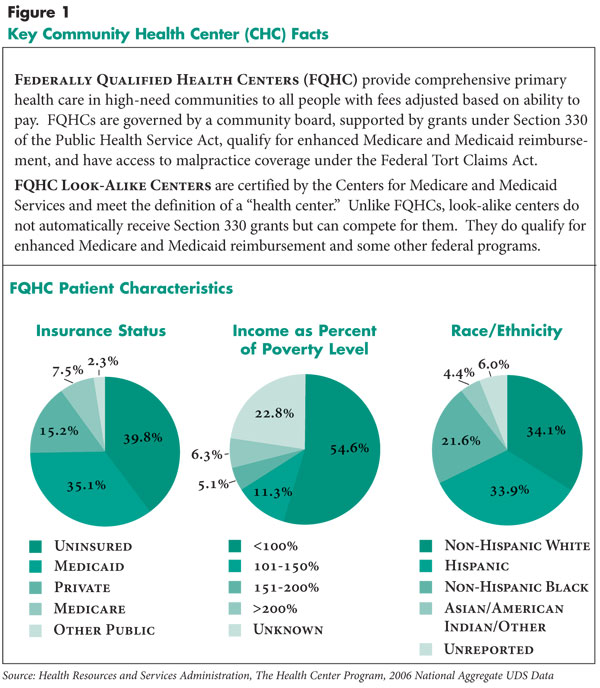

![]() ince 2000, federal funding for federally qualified community health centers—key providers of preventive and primary care for underserved people—has doubled to nearly $2 billion annually in 2006, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). More than 16 million patients—primarily racial or ethnic minorities, low income, uninsured or covered by Medicaid—received care at more than 1,100 federally qualified and look-alike CHCs in 2006, up from just over 10 million patients in 2001 (see Page 3 for CHC definitions and patient characteristics).

ince 2000, federal funding for federally qualified community health centers—key providers of preventive and primary care for underserved people—has doubled to nearly $2 billion annually in 2006, according to the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). More than 16 million patients—primarily racial or ethnic minorities, low income, uninsured or covered by Medicaid—received care at more than 1,100 federally qualified and look-alike CHCs in 2006, up from just over 10 million patients in 2001 (see Page 3 for CHC definitions and patient characteristics).

Much of the recent federal investment has gone to building health centers in additional communities, while support for existing CHCs has not kept pace with operating expense increases and patient growth.1 At the same time, recruiting and retaining staff members in a competitive labor market has grown more difficult, and external entities have increased requirements that CHCs must meet to stay in operation and to provide state-of-the-art clinical care, as well as to address racial and ethnic disparities and public health issues.

HSC’s 2007 site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities—home to more than 100 federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) and look-alike facilities—explored how CHCs are responding to rising demand for services, funding challenges, and other new responsibilities (see Data Source). Many communities have other types of health centers, such as free clinics or public clinics, but results presented here focus on federally qualified and look-alike community health centers.

Back to Top

|

Click here to view this figure as a PowerPoint slide.

More Patients

![]() irtually all CHC directors reported treating more patients—mainly

uninsured—over the last two years, leading to stressed capacity and, in

some cases, longer waits for appointments. Observers attributed the increase

in uninsured people to declining employer-based insurance, growing numbers of

immigrants who lack coverage, and Medicaid cutbacks. While the number of uninsured

patients treated at FQHCs increased from 4 million in 2001 to 6 million in 2006,

according to HRSA,2 the overall proportion of uninsured

patients remained steady at about 40 percent in 2006. CHCs also serve a significant

number of Medicaid patients—about 35 percent of all FQHC patients have Medicaid

coverage. CHCs benefit from serving Medicaid patients because their Medicaid

payment rates typically are higher than rates paid by private insurers or directly

by patients. Changes in Medicaid physician payment rates affect CHCs indirectly.

Reductions in payment rates to private physicians in some states, such as Michigan

and California, made access to private providers more difficult for people with

Medicaid coverage, increasing demand for care at CHCs. Conversely, in some cases,

increased Medicaid payment rates may reduce a health center’s proportion of

Medicaid patients. In Orange County, Phoenix and Greenville, CHCs have faced

new competition for Medicaid patients when rates increased to selected providers,

such as obstetricians.

irtually all CHC directors reported treating more patients—mainly

uninsured—over the last two years, leading to stressed capacity and, in

some cases, longer waits for appointments. Observers attributed the increase

in uninsured people to declining employer-based insurance, growing numbers of

immigrants who lack coverage, and Medicaid cutbacks. While the number of uninsured

patients treated at FQHCs increased from 4 million in 2001 to 6 million in 2006,

according to HRSA,2 the overall proportion of uninsured

patients remained steady at about 40 percent in 2006. CHCs also serve a significant

number of Medicaid patients—about 35 percent of all FQHC patients have Medicaid

coverage. CHCs benefit from serving Medicaid patients because their Medicaid

payment rates typically are higher than rates paid by private insurers or directly

by patients. Changes in Medicaid physician payment rates affect CHCs indirectly.

Reductions in payment rates to private physicians in some states, such as Michigan

and California, made access to private providers more difficult for people with

Medicaid coverage, increasing demand for care at CHCs. Conversely, in some cases,

increased Medicaid payment rates may reduce a health center’s proportion of

Medicaid patients. In Orange County, Phoenix and Greenville, CHCs have faced

new competition for Medicaid patients when rates increased to selected providers,

such as obstetricians.

Additionally, new documentation requirements under the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 adversely affected Medicaid coverage in some states, resulting in more uninsured CHC patients. Increased numbers of immigrants, without access to either employer-sponsored or publicly supported coverage, have grown increasingly reliant on CHCs, in part because centers are exempted from any obligation to ask an individual’s legal status.

Back to Top

Fewer Care Alternatives

![]() he growth in uninsured people seeking care at CHCs also

reflects a decline in alternative sites of care. In the last decade, the amount

of charity care provided by physicians has declined significantly. 3

Though many physicians donate time to free clinics and to specialty care banks,

such as Project Access in Seattle and Little Rock or MedWell Access in Greenville,

demand outstrips supply.

he growth in uninsured people seeking care at CHCs also

reflects a decline in alternative sites of care. In the last decade, the amount

of charity care provided by physicians has declined significantly. 3

Though many physicians donate time to free clinics and to specialty care banks,

such as Project Access in Seattle and Little Rock or MedWell Access in Greenville,

demand outstrips supply.

CHCs face serious challenges referring both uninsured and Medicaid patients to specialists; one veteran Seattle observer noted CHCs are “back to begging for specialty care almost like the 1970s,” when there were fewer specialists relative to the population. In other markets, such as Orange County, academic health centers—often cornerstones of the safety net—have undertaken initiatives to shift uninsured patients in their emergency departments (EDs) and outpatient clinics to community providers. In Greenville and Little Rock, as in many communities, the local health department has been phasing out direct primary care services, creating new demands for CHC services.

In several states, reductions in funding for mental health services have led to dramatic increases in patients with mental health conditions seeking care at CHCs. Dental care for low-income adults is another service that in a number of communities, such as Orange County and Little Rock, is available primarily at CHCs and often is limited to basic services. Nationally, the number of patients receiving mental health care at CHCs grew by almost 170 percent between 2001 and 2006, according to HRSA, while the number of patients receiving dental services grew by more than 80 percent during the same period.4

Back to Top

Recruiting and Retaining

![]() HCs offer comprehensive services that are important in caring for persons with chronic conditions. In addition to clinical teams, many CHCs offer on-site diagnostic testing, subsidized pharmacies, transportation and patient education programs. To offer this range of services, CHCs rely on physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and other clinical and administrative staff. CHC directors reported increased difficulty recruiting and retaining clinical staff because they must compete with other health care providers, especially hospitals, that offer comparatively better salaries and benefits.

HCs offer comprehensive services that are important in caring for persons with chronic conditions. In addition to clinical teams, many CHCs offer on-site diagnostic testing, subsidized pharmacies, transportation and patient education programs. To offer this range of services, CHCs rely on physicians, nurse practitioners, physician assistants and other clinical and administrative staff. CHC directors reported increased difficulty recruiting and retaining clinical staff because they must compete with other health care providers, especially hospitals, that offer comparatively better salaries and benefits.

Attracting bilingual staff is becoming more challenging for CHCs as other providers also attempt to improve cultural and linguistic competencies. Further, the general shortage of primary care physicians in many communities presents serious recruitment problems. In Boston, CHCs reported sharply increasing starting salaries for primary care physicians to better compete with hospitals and medical groups.

Many CHCs continue to rely on National Health Service Corps physicians who receive federal assistance in repaying medical school loans in exchange for working in medically underserved areas. Few centers attempt to recruit specialists, given restrictions on use of federal grant funds for hiring specialists, and most centers cannot generate sufficient revenue from other sources to fully support specialists.

Back to Top

Increased Emphasis on Accountability, Disparities and Public Health

![]() hile CHCs have been subject to federal monitoring and reporting requirements for many years, they now face increasing expectations from grantmakers and public and private payers. Some CHCs reported demands to more formally demonstrate their need for funds and how they will use them. One CHC director characterized the attitudes of philanthropies as, “Before they would say, ‘Let’s give money to people who do good things;’ now they want outcome measures, logic models and more accountability.” Though hardly a new phenomenon for CHCs, Medicaid managed care also is being extended to new populations in a number of markets, and these plan contracts carry new terms, relationships and reporting obligations. Reporting on clinical performance measures also is on the rise from public and private sources, though reporting is typically neither coordinated nor uniform. Community-wide public reporting and quality improvement collaborations are underway in Seattle, Cleveland and Little Rock, presenting new expectations for integration of CHC performance improvement efforts with those of private providers.

hile CHCs have been subject to federal monitoring and reporting requirements for many years, they now face increasing expectations from grantmakers and public and private payers. Some CHCs reported demands to more formally demonstrate their need for funds and how they will use them. One CHC director characterized the attitudes of philanthropies as, “Before they would say, ‘Let’s give money to people who do good things;’ now they want outcome measures, logic models and more accountability.” Though hardly a new phenomenon for CHCs, Medicaid managed care also is being extended to new populations in a number of markets, and these plan contracts carry new terms, relationships and reporting obligations. Reporting on clinical performance measures also is on the rise from public and private sources, though reporting is typically neither coordinated nor uniform. Community-wide public reporting and quality improvement collaborations are underway in Seattle, Cleveland and Little Rock, presenting new expectations for integration of CHC performance improvement efforts with those of private providers.

Since almost two-thirds of CHC patients are members of racial or ethnic minorities and nearly 30 percent of patients require interpretation services, health centers are on the front lines in trying to reduce racial and ethnic disparities.5 In 1998, HRSA began sponsoring Health Disparities Collaboratives to bring federally qualified health centers together to learn quality improvement approaches developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.6 Most health centers in the 12 HSC communities are now veterans of the collaboratives, and CHC directors reported these activities have not only helped improve delivery systems and processes of care for all of their patients, but also promoted a culture of continuous quality improvement.

Additionally, CHCs are preparing for potential public health emergencies in their communities. In some cases, this has been a challenge for CHCs that until recently were overlooked by state and local agencies developing preparedness plans. This situation is beginning to change, however, as one respondent from Phoenix remarked, “I guess they finally realized that the neediest population will probably show up at the clinics in the case of a disaster.” Several CHCs are coordinating with community providers, stockpiling supplies and applying for grants for communication equipment and generators. A Boston CHC even hired a full-time employee to work with community agencies and providers on emergency preparedness.

CHCs also have other new public health responsibilities and priorities. A health center in northern New Jersey has been given responsibility for taking over tuberculosis testing from the county health department. A number of health centers have expanded their mission to include participating in or developing various wellness campaigns, which can require more staff and funding.

Back to Top

CHCs Respond to Mounting Challenges

![]() n the past two years, new health centers have opened in three of the 12 communities, and CHCs in all but four communities added additional practice sites. Growth was particularly pronounced in Miami and northern New Jersey—communities that also benefited from increased state support. Boston, with the largest concentration of health centers in the country, also saw two new sites open. Other centers have expanded hours to include Saturdays and evenings to treat more patients and help improve access for people who cannot take time off from work to seek care. In some communities, CHCs are expanding hours to provide alternatives to hospital emergency department use.

n the past two years, new health centers have opened in three of the 12 communities, and CHCs in all but four communities added additional practice sites. Growth was particularly pronounced in Miami and northern New Jersey—communities that also benefited from increased state support. Boston, with the largest concentration of health centers in the country, also saw two new sites open. Other centers have expanded hours to include Saturdays and evenings to treat more patients and help improve access for people who cannot take time off from work to seek care. In some communities, CHCs are expanding hours to provide alternatives to hospital emergency department use.

Broadening of services at existing facilities is also evident, with centers in northern New Jersey and Phoenix expanding mental health services. Other health centers are adding pharmacies and dental services to meet patient needs. The largest health center in Indianapolis has developed an obstetric hospitalist program to meet the inpatient needs of maternity patients.

A number of health centers report major steps in developing new infrastructure, particularly information technology (IT). In Boston, most health centers have electronic medical records (EMRs) and are electronically connected to their affiliated safety net hospitals. A similar approach is under development with three Cleveland health centers and the public hospital. In Miami, the CHCs have organized a regional health information organization to create a shared medical record, and Seattle CHCs have a similar partnership for IT services. Despite these activities, there is significant variation in IT and EMR adoption across communities and health centers, with the costs of developing such systems often prohibitive.7

In several communities, CHCs have forged relationships with other parts of the local health care delivery system to improve low-income people’s access to appropriate care. The United Way in Greenville is supporting the development of formal referral mechanisms between hospitals and community health centers. In other cases, public policy makers and health plans have been instrumental in encouraging CHCs to be effective, available alternatives to more costly sites of care, such as hospital emergency departments.

Many health centers are collaborating with their safety net hospital counterparts and other organizations to expand access to needed services. Enhanced financial screening systems for public hospital patients in Phoenix and Cleveland have made free or deeply discounted specialty and ancillary care more readily accessible to CHC patients. In Miami, CHCs are working with the school system to expand school-based services, with the added potential of freeing up appointments at CHC sites because children can now be treated at school. In Phoenix, health centers have partnered with new dental schools to provide teaching sites, volunteer opportunities, and, ultimately, post-graduation employment as a means to “grow their own” future clinicians.

A major aim in some communities has been to pursue federal qualification or look-alike status for community clinics supported only with private donations and fees. In Orange County, a community with only two federally qualified health centers for a population of approximately 3 million, as many as five community clinics are now seeking or have obtained federally qualified or look-alike health center status. In Phoenix, obtaining look-alike status for the 11 centers sponsored by the county health authority meant a substantial infusion of new revenue.

Attracting more Medicare and privately insured patients also is a goal for some centers, including those in Boston, northern New Jersey, Greenville and Cleveland. However, payment for care of these patients is typically less than what CHCs receive for patients with Medicaid coverage.

A number of health centers have bolstered relationships with philanthropic organizations to obtain needed capital for new initiatives. One Phoenix CHC obtained a major grant from the Diamondbacks baseball team foundation to acquire a mobile health unit that now serves 10 school clinics and migrant and farm workers. United Way and Duke Endowment funds have supported a new dental initiative in the Greenville area at the CHC and other sites of care.

Many of the CHCs have longstanding relationships with not-for-profit local hospital systems that support CHCs as part of their community benefit obligations, an area of increased scrutiny on the part of federal, state and local policy makers.

Back to Top

Future Risks and Opportunities

![]() ver the past two years, many community health centers have responded to increasing demands for services and new responsibilities in the face of serious financial constraints. Beyond the usual concerns of ensuring adequate funding to meet their missions, many CHC directors are anxious about how strategies aimed at universal coverage underway in several states will affect them and whether reformers will be mindful of the issues facing health centers.

ver the past two years, many community health centers have responded to increasing demands for services and new responsibilities in the face of serious financial constraints. Beyond the usual concerns of ensuring adequate funding to meet their missions, many CHC directors are anxious about how strategies aimed at universal coverage underway in several states will affect them and whether reformers will be mindful of the issues facing health centers.

CHCs are likely to benefit from caring for previously uncovered persons who bring additional revenue, if CHCs can make or keep themselves attractive to these patients. Whether that revenue will be adequate to compensate CHCs for the range of services they now provide is uncertain. Also unclear is how care will be financed for people who remain uninsured and for services that will be needed but either not covered or extremely restricted by payers.

At the same time, CHCs appear well positioned to inform the growing call for renewed emphasis on “patient-centered medical homes.”8 CHCs’ model of care closely approximates the ideal type being advanced by proponents, and the fact that CHCs have been reimbursed for the comprehensive care they provide has enabled them to play this role. CHCs have established team-based care models that others could examine and emulate, and their progress in recent years in service expansions, infrastructure development and quality improvement initiatives underscores the potential yield from investing in such arrangements.

Back to Top

Notes

| 1. | National Association of Community Health Centers, Inc. (NACHC), A Sketch of Community Health Centers: Chart Book 2006, www.nachc.com/research/Files/ChartBook2006.pdf (Accessed Oct. 18, 2007). |

| 2. | Health Resources and Services Administration, The Health Center Program,

2006 National Aggregate UDS Data, www.bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/2006data/National/NationalTable4Universal.htm

(Accessed Nov. 7, 2007). |

| 3. | Cunningham, Peter J., and Jessica H. May, A Growing Hole in the Safety Net: Physician Charity Care Declines Again, Tracking Report No. 13, Center for Studying Health System Change, Washington, D.C. (March 2006). |

| 4. | Health Resources and Services Administration, The Health Center Program, The President’s Health Center Initiative, www.bphc.hrsa.gov/presidentsinitiative/ (Accessed Nov. 5, 2007). |

| 5. | Health Resources and Services Administration, The Health Center Program,

2006 National Aggregate UDS Data, www.bphc.hrsa.gov/uds/2006data/National/NationalTable4Universal.htm

(Accessed Nov. 7, 2007). |

| 6. | Landon, Bruce E., et al., “Improving the Management of Chronic Disease at Community Health Centers,” New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 356, No. 9 (March 1, 2007). |

| 7. | Shields, Alexandra, et al., “Adoption Of Health Information Technology

In Community Health Centers: Results Of A National Survey” Health

Affairs, Vol. 26, No. 5 (September/October 2007). |

| 8. | “Joint Principles of the Patient-Centered Medical Home” issued

by the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Pediatrics,

the American College of Physicians and the American Osteopathic Association

(February 2007). |

Back to Top

Data Source

Approximately every two years, HSC conducts site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities as part of the Community Tracking Study to interview health care leaders about the local health care market, how it has changed and the effect of those changes on people. The communities are Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis; Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County, Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. The sixth round of site visits was conducted between February and June 2007 with more than 500 interviews. This Issue Brief is based primarily on responses from community health center and safety net hospital executives, state policy makers, local health department directors and consumer advocates. In each community, the one or two largest community health centers were typically targeted for interview.

Back to Top

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org