State Prescription Drug Price Web Sites: How Useful to Consumers?

HSC Research Brief No. 1

February 2008

Ha T. Tu, Catherine Corey

To aid consumers in comparing prescription drug costs, many states have launched Web sites to publish drug prices offered by local retail pharmacies. The current push to make retail pharmacy prices accessible to consumers is part of a much broader movement to increase price transparency throughout the health-care sector. Efforts to encourage price-based shopping for hospital and physician services have encountered widespread concerns, both on grounds that prices for complex services are difficult to measure and compare accurately and that quality varies substantially across providers. Experts agree, however, that prescription drugs are much easier to shop for than other, more complex health services.

However, extensive gaps in available price information—the result of relying on Medicaid data—seriously hamper the effectiveness of state drug price-comparison Web sites, according to a new study by the Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC).

An alternative approach—requiring pharmacies to submit price lists to the states—would improve the usefulness of price information, but pharmacies typically oppose such a mandate. Another limitation of most state Web sites is that price information is restricted to local pharmacies, when online pharmacies, both U.S. and foreign, often sell prescription drugs at substantially lower prices. To further enhance consumer shopping tools, states might consider expanding the types of information provided, including online pharmacy comparison tools, lists of deeply discounted generic drugs offered by discount retailers, and lists of local pharmacies offering price matches.

- States Seek to Boost Price Transparency at Retail Phamacy Level

- State Web Sites Share Key Limitations on Price Information

- A Closer Look at Florida’s Web Site, MyFloridaRx.com

- Policy Implications

- Notes

- Data Source

States Seek to Boost Price Transparency at Retail Pharmacy Level

![]() s the rising costs of prescription drugs and increasing numbers of uninsured Americans have led policy makers to examine different approaches toward helping consumers better afford the medications they need, many state governments are focusing on initiatives to increase price transparency in retail pharmacy markets. These states have implemented Web sites that publish prices charged by local pharmacies for common prescription medications to help consumers identify and purchase from the pharmacies offering the lowest prices.

s the rising costs of prescription drugs and increasing numbers of uninsured Americans have led policy makers to examine different approaches toward helping consumers better afford the medications they need, many state governments are focusing on initiatives to increase price transparency in retail pharmacy markets. These states have implemented Web sites that publish prices charged by local pharmacies for common prescription medications to help consumers identify and purchase from the pharmacies offering the lowest prices.

The current push to make retail pharmacy prices accessible to consumers is part of a much broader movement to increase price transparency throughout the health care system. Efforts to encourage price-based shopping for hospital and physician services have encountered widespread concerns, both on grounds that prices for complex services are difficult to measure and compare accurately and that quality varies substantially across providers. Experts agree, however, that prescription drugs are much easier to shop for than other, more complex health services. First, for any given prescription, prices are completely comparable across providers. Second, quality variations across retail pharmacies do not appear to be a major concern to experts familiar with this market. Pharmacies do differ significantly on some dimensions, such as location and customer service, but these are likely to be characteristics that consumers can assess themselves.

Some observers are concerned about one aspect of shopping for drugs: If a consumer needs multiple medications and buys each at a different pharmacy to maximize cost savings, no single pharmacy will be aware of the consumer’s full medication list, and the consumer will not be alerted to any adverse drug interactions that might occur.1 A leading consumer organization, however, notes that while such concerns are valid, they should not preclude multiple-pharmacy shopping by consumers, as long as consumers present their full medication list and ask about possible drug interactions at each pharmacy they use.2

While conditions in the retail pharmacy market generally are conducive to consumer shopping, this market has some characteristics that may limit the usefulness or relevance of drug price comparison initiatives launched by state governments. First, programs that compare prices only at pharmacies located within a state do not take into account the presence of online pharmacies, both in the U.S. and abroad, that often sell drugs for substantially less than local pharmacies.

Second, insured and uninsured consumers face different retail prices for their prescriptions, and the usual and customary prices posted by state drug price comparison initiatives generally are relevant only to the uninsured.3 Insured consumers typically are eligible for prescription drug prices negotiated by pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), which use volume purchasing power to obtain lower prices. Even insured consumers who are paying completely out of pocket—because they have not yet met a deductible—typically are eligible for these negotiated prices and often have access to online price tools provided by PBMs. It would be more accurate, therefore, to regard the true audience for these state initiatives as the subgroup of uninsured people needing prescription drugs, rather than the larger population of all “consumers” or all “state residents” that most state programs have identified as their audience.

In addition, the usefulness and relevance to consumers of states’ drug price comparison initiatives are largely determined by how well each state implements its program—in particular, how comprehensive, accurate and current the price information is, and how easy the Web site is to access, navigate and understand. This study presents the findings of an assessment of state drug price comparison programs (see Data Source), identifies several key factors limiting the programs’ usefulness to consumers, and presents key policy options for states seeking to help consumers reduce prescription drug costs.

Back to Top

State Web Sites Share Key Limitations on Price Information

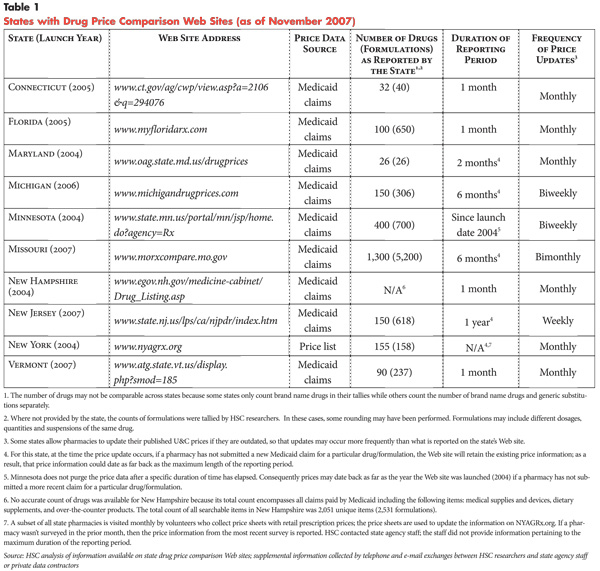

![]() s of late 2007, 10 states were actively maintaining Web

sites providing prescription drug prices available at the state’s retail pharmacies

(see Table 1). More states, including California, are

about to launch Web sites, while a few states, including Ohio and Washington,

have discontinued previous initiatives. The 10 active state Web sites vary considerably

on a number of key dimensions: the number of drugs with prices reported, the

number of formulations reported per drug, the duration of the data reporting

period, and the frequency of price data updates.

s of late 2007, 10 states were actively maintaining Web

sites providing prescription drug prices available at the state’s retail pharmacies

(see Table 1). More states, including California, are

about to launch Web sites, while a few states, including Ohio and Washington,

have discontinued previous initiatives. The 10 active state Web sites vary considerably

on a number of key dimensions: the number of drugs with prices reported, the

number of formulations reported per drug, the duration of the data reporting

period, and the frequency of price data updates.

Data Source and Data Comprehensiveness. Most states with drug price comparison Web sites determine which drugs to include by consulting lists of commonly prescribed drugs—either a state-specific list from the state Medicaid agency or a national list obtained from commercial sources. Among the state Web sites, the number of drugs with price information varied widely, ranging from as few as 26 drugs in Maryland to as many as 400 drugs in Minnesota. Two states, Missouri and New Hampshire, include any drug for which a Medicaid claim was submitted during the reporting period.4 Some states exclude drugs that have the potential to be abused—including painkillers like hydrocodone and lifestyle drugs like Viagra—no matter how commonly prescribed.

Most state Web sites provide price data for multiple formulations of the same drug, which often can be prescribed in several dosage levels and forms (e.g., capsule, liquid). Florida, for example, presents price data for 650 different drug formulations, representing 100 distinct drugs.5 In contrast, Maryland offers price data for only one formulation per drug—an approach that limits the Web site’s usefulness.

Comprehensiveness of drug price information depends not just on the number of drugs and formulations covered, but also the completeness of price information provided for those drugs. For example, a Web site that has a long drug list but contains a great deal of missing price information would offer consumers limited shopping opportunities. The analysis found that, among all the states with drug price comparison Web sites, none has a data collection approach that provides complete pharmacy price data, because none requires pharmacies to report drug prices.

All but one of the states with drug price comparison Web sites use Medicaid claims data to obtain price information. Specifically, usual and customary price data are collected from claim forms submitted by pharmacies for prescription drug transactions for Medicaid patients. The usual and customary price is not the actual price paid by Medicaid for prescription drugs; it generally represents the retail price that a pharmacy charges to a cash-paying customer, absent any discount. In many states, this price often is reported on Medicaid claim forms. Using these prices obtained from Medicaid claims has been popular among states undertaking price transparency initiatives, largely because the data are readily available to state governments, which incur little additional cost in making the information available on state-hosted Web sites. In addition, this data collection strategy involves no added reporting burden or cost to retail pharmacies, and so does not encounter resistance from pharmacies or their trade associations. However, the clear drawback to using Medicaid claims data is that price information will only be available on the Web site in cases where a pharmacy submitted a Medicaid claim that contained usual and customary price information for a particular drug during the reporting period.

New York is the only state that does not rely on Medicaid claims data for prescription drug retail price information.6 A 2002 state law requires that retail pharmacies provide walk-in customers with prescription price lists on request. The New York drug price comparison program currently uses volunteers to collect these price lists from retail pharmacies. To date, this data collection approach has resulted in severely limited price information. A search of the New York Web site revealed, for example, that price data for the most commonly prescribed drugs, such as Lipitor, were available for only four pharmacies in Manhattan. In addition, the price information was not very current: A Web site search conducted in October 2007 found price data pertaining to April 2007.

Timeliness of Price Information. Most states with drug comparison Web sites have a one-month reporting period and a monthly data update schedule. This schedule, if adhered to, would allow consumers to access relatively recent price data. An examination of state Web sites, however, found that some states’ data updates have lagged behind schedule by a few months, so that the posted price information was not as current as intended. This problem may result, at least in part, from the fact that these Web sites generally lack dedicated staff and funding, and that responsibility for these Web sites tend to be split between two agencies (often with the state Medicaid agency providing the price data and pharmacy information, and the Attorney General’s office developing and maintaining the Web site).

A reporting period of only one month poses problems for the comprehensiveness of the price data (i.e., the number of pharmacies reporting a price for each drug). In response to this problem, some states have opted to use longer reporting periods—for example, six months (Michigan, Missouri), one year (New Jersey), or even dating back to the inception of the Web site (Minnesota)—to reduce the amount of missing price data. In an effort to make the price data as current as possible, while still maintaining comprehensiveness, most of these states have adopted frequent data update schedules—weekly updates in New Jersey and biweekly updates in Michigan and Minnesota. With each update, if new drug price data are available, the new data replace older data; if no new price data are available, then the existing data remain on the Web site until the data collection period expires.

This approach—an effort to balance competing objectives of data comprehensiveness and timeliness—provides a much fuller set of price data than would be possible with a shorter reporting period. But the information can be misleading to consumers, because the prices listed for the same drug at competing pharmacies may have been obtained at different times over an extended reporting period, and older prices are less likely to still be in effect. Of the states using this approach, only New Jersey posts the date on which each price was reported. Michigan and Missouri provide general disclaimers that posted price information may be out of date and encourage consumers to call pharmacies directly to double-check prices.

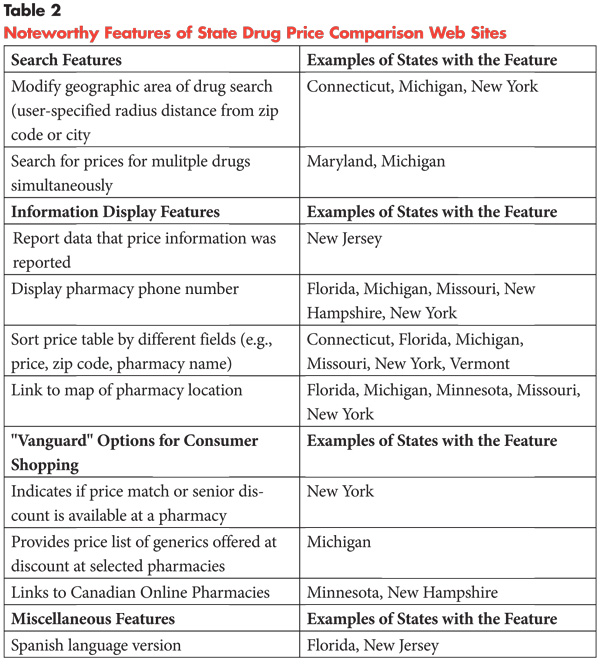

Noteworthy Features of State Web Sites. Some state sites have features that may be particularly useful to consumers (see Table 2). These features enhance flexibility and usability on several different dimensions: search capabilities, information display and consumer shopping options. States seeking to launch new Web sites or improve existing ones may want to consider replicating some of these features.

In terms of search capabilities, two features are noteworthy. The first pertains to selection of the geographic area. Three states allow consumers to specify a search area within a radius distance (e.g., 5 or 10 miles) from a central point of a zip code; one of these states also allows this search function from a central point of a city. This feature offers consumers greater flexibility since they can specify a travel distance they consider reasonable, which may not coincide with the boundaries of any one county, city or zip code. The second search feature that may be particularly useful to consumers pertains to drug selection. Two Web sites allow consumers to specify multiple drugs on which to perform simultaneous price searches (6 drugs in Maryland; 5 in Michigan). For consumers shopping for multiple drugs, this feature yields a very useful price table, which presents side-by-side comparisons of each of the requested drug prices offered by each pharmacy.

Once a drug price search has been conducted and a price table has been generated, several information display features are helpful to consumers. The first two help the consumer to assess the accuracy of the price information. The first feature, not provided by most states, is a display of the date when each drug price was obtained, allowing consumers to assess how current the price data is. The second feature, offered by several states, is a display of pharmacy contact information, making it easy for consumers to call pharmacies to verify prices. Other information display features that may be helpful to consumers include the ability to sort the price table by various fields (e.g., drug prices), and the inclusion of mapping tools to help consumers locate pharmacies.

In addition, there are three useful features that go beyond the information provided by most Web sites in enhancing consumers’ drug shopping options. First, one state (New York) identifies which pharmacies will match prices offered by other local stores; this feature would enable consumers to obtain the lowest (local) prices with one-stop shopping. Second, another state (Michigan) provides a price table showing which generic drugs are available at steeply discounted prices at particular pharmacies (including Wal-Mart, Sam’s Club, Target, Kmart and Meijer, a local discount chain). This price list gives consumers a straightforward, easy-to-use tool for locating low prices for many generics. Finally, Minnesota and New Hampshire offer a feature that expands drug comparison shopping beyond the local geographic area. They provide links from their sites to Canadian online pharmacies and instructions for ordering from those pharmacies. For consumers needing brand-name medications, Canadian sites offer potentially large savings.

Finally, Florida and New Jersey offer Spanish-language versions of their Web sites, which may be useful in expanding the programs’ reach.

Back to Top

A Closer Look at Florida’s Web Site, MyFloridaRx.com

![]() lorida’s program was selected for in-depth analysis because it is the most prominent and well known, and among the most long-standing, of the state pharmacy price transparency initiatives. Florida’s Web site, MyFloridaRx.com, was assessed on a variety of dimensions, including availability and accuracy of price information and overall usability. The analysis was conducted beginning in mid-2007, using the price data posted at that time on MyFloridaRx.com, which pertained to prices reported as being in effect in April 2007. The prices reported on MyFloridaRx.com are usual and customary prices obtained from Medicaid claims forms. To conduct the analysis of MyFloridaRx.com, drug price searches were conducted using two strategies—a Top 10 drug list and a set of consumer drug profiles—applied in different geographic markets: urban, suburban and rural.

lorida’s program was selected for in-depth analysis because it is the most prominent and well known, and among the most long-standing, of the state pharmacy price transparency initiatives. Florida’s Web site, MyFloridaRx.com, was assessed on a variety of dimensions, including availability and accuracy of price information and overall usability. The analysis was conducted beginning in mid-2007, using the price data posted at that time on MyFloridaRx.com, which pertained to prices reported as being in effect in April 2007. The prices reported on MyFloridaRx.com are usual and customary prices obtained from Medicaid claims forms. To conduct the analysis of MyFloridaRx.com, drug price searches were conducted using two strategies—a Top 10 drug list and a set of consumer drug profiles—applied in different geographic markets: urban, suburban and rural.

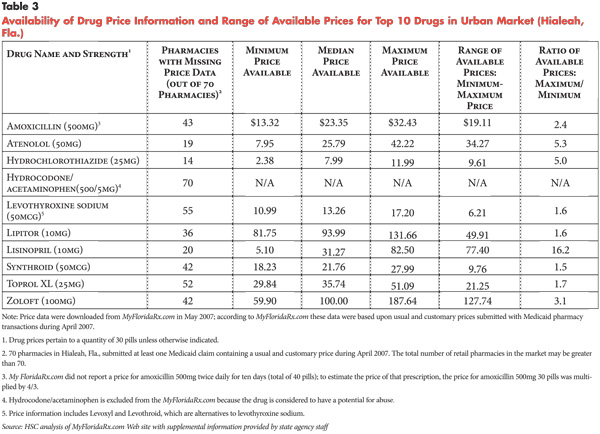

Price Availability: Top 10 Drug List. The Top 10 drug list, obtained from a large pharmacy benefit manager, was used to assess the comprehensiveness of price information available from MyFloridaRx.com. If the Web site was missing price data from a substantial proportion of pharmacies for these drugs, then the problem of missing data was likely to be at least as extensive for other, less commonly prescribed drugs. The key finding from the Top 10 drug analysis was that the extent of missing price data was substantial and widespread across the urban, suburban and rural markets studied.

The urban market examined in this analysis encompasses a radius of approximately 2.5 miles centered on the city of Hialeah, in Miami-Dade County. This market was selected for analysis because it contained an especially high number of retail pharmacies (70) in a relatively compact geographic area, and thus appeared to provide conditions especially conducive to consumer shopping and pharmacy competition.

In the urban Hialeah market, none of the Top 10 drugs had price information available from all the local pharmacies (see Table 3). The three drugs with the most available price information still were lacking price data for 20 percent to 29 percent of the 70 pharmacies in the city. The other seven drugs were missing price data from at least half the pharmacies in the market. Among these seven drugs, two were missing at least three-quarters of their price data, and one drug (hydrocodone/acetaminophen) was excluded altogether from MyFloridaRx.com, because it is a pain medication considered subject to abuse.

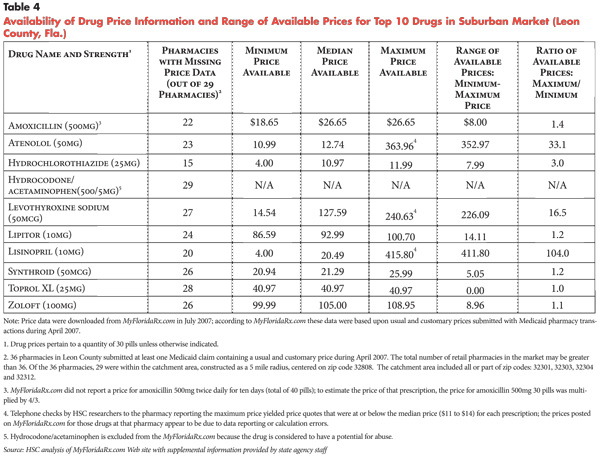

When the analysis of price availability for the Top 10 drugs was replicated in a suburban market—Leon County in the Tallahassee area—the problems with missing data were exacerbated. In this suburban market, containing 29 pharmacies within an approximate radius of 5 miles, all 10 of the most common drugs had missing data for more than half of the pharmacies; all but one drug had missing data for two-thirds or more of the pharmacies; and a few drugs had almost completely missing data (see Table 4). This problem apparently resulted from low numbers of Medicaid pharmacy transactions taking place in this suburban market, leading to very sparse price information.

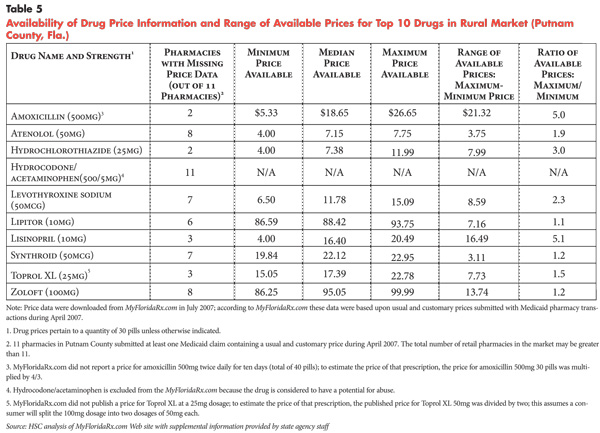

In rural Putnam County—a market with 11 pharmacies within a radius of approximately 15 miles from the county’s center—missing price information for the Top 10 drugs was less of a problem than it was for suburban Leon County (see Table 5), because pharmacies in rural Putnam County saw greater concentrations of Medicaid pharmacy transactions. Still, the proportion of Putnam County pharmacies with missing price information was substantial, ranging from 18 percent to 100 percent across the Top 10 drugs. Compared to the urban Hialeah market, Putnam County had lower proportions of missing data for some Top 10 drugs. However, the much smaller number of pharmacies (11 vs. 70) spread over a substantially larger travel distance (15-mile vs. 2.5-mile radius) likely makes missing price information a more serious impediment for would-be comparison shoppers in rural markets compared to urban settings.

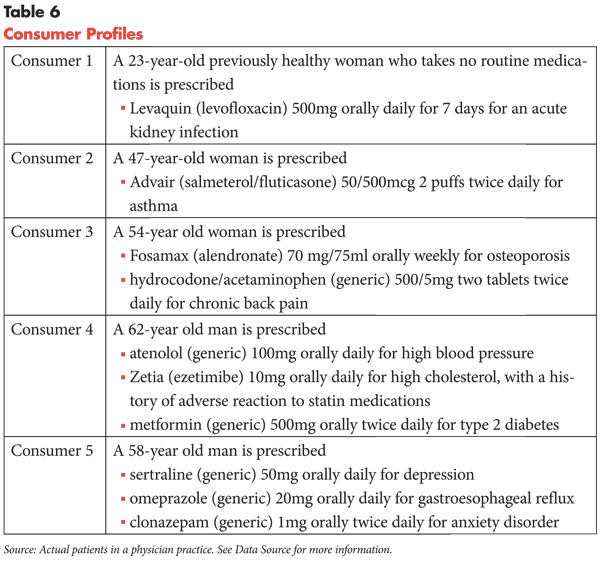

Price Availability and Web Site Usability: Consumer Profiles. In a separate assessment of price availability on MyFloridaRx.com, drug profiles were created to represent five consumers with a range of medical conditions and prescription drug needs (see Table 6). Consumers 1 and 2 need only one prescription each, while Consumers 3, 4 and 5 each need at least two drugs each for multiple health conditions. Consumer 1 has a one-time medication need to treat an acute condition, while the other four consumers have ongoing drug needs to treat chronic conditions. The analysis of the consumer drug profiles used the same 2.5-mile-radius urban market, Hialeah, employed in the Top 10 drug analysis.

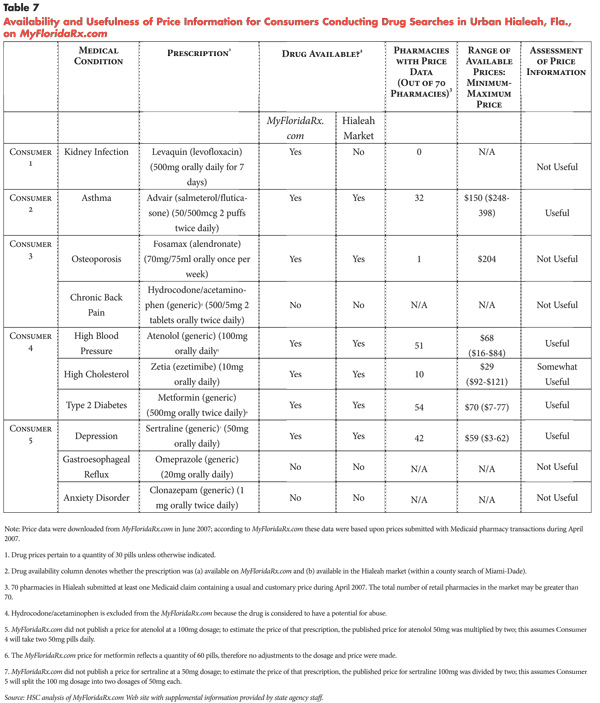

Among the five consumers, Consumer 2, taking Advair to treat asthma, would find MyFloridaRx.com the most useful in finding price information relevant to her drug needs (see Table 7). Price information on Advair is far from complete, with fewer than half (32 of 70) of the pharmacies reporting Advair price data. However, the number of available pharmacies and the price range among those pharmacies are both large enough that Consumer 2 has the potential to reap substantial savings from using the Web site to compare prices for Advair.

Consumer 4, needing three prescriptions to treat three chronic conditions, would find MyFloridaRx.com useful in comparing prices for two of his drugs and less useful for the third. Both atenolol (for high blood pressure) and metformin (for diabetes) have price data available for approximately three-quarters of Hialeah pharmacies, and the price ranges for both drugs are large enough to suggest considerable savings from comparison shopping.7 The other drug prescribed for Consumer 4, Zetia (for high cholesterol), has much less price information—with only 10 of 70 pharmacies in Hialeah reporting a price—and a narrower price range among the available pharmacies, so the usefulness of the Web site in comparing Zetia prices is considerably more limited than for the two other drugs. To obtain the lowest available prices for Consumer 4’s three drugs, as reported by MyFloridaRx.com, Consumer 4 would need to visit three different pharmacies, with a travel distance of eight miles among the pharmacies (not counting any travel time from the consumer’s home or workplace to reach the pharmacies).

Consumer 5, who also needs three prescriptions to treat three different chronic conditions, would find the Florida Web site useful in comparing prices for only one of his three prescribed medications—sertraline (for depression), which has price information from 42 of Hialeah’s 70 pharmacies and a considerable price spread among pharmacies.8 The other two drugs needed by this consumer, omeprazole (for gastroesophageal reflux) and clonazepam (for anxiety disorder) are not available at all on MyFloridaRx.com. Overall, Consumer 5 would find the Web site’s usefulness quite limited.

The two remaining consumers would not find MyFloridaRx.com helpful in comparing prices for the medications they need. Even though Consumer 1 has only a single prescription need—the brand-name antibiotic Levaquin (for an acute infection)—the drug would not appear in a search within Hialeah because no Medicaid claims for this drug were submitted by Hialeah pharmacies for April 2007. MyFloridaRx.com advises users to expand the geographic search area if the drug is not available for the initial search area. In this instance, Consumer 1 could have widened the search area to Miami-Dade County and would have found the nearest pharmacy quoting a price to be 8 miles from central Hialeah and the nearest pharmacy quoting the lowest (county-wide) price to be 10 miles away. It is unclear whether a consumer with a one-time need for a seven-day prescription would be motivated to comparison shop, particularly if obtaining a lower price requires significant travel distance.

The other consumer whose needs would not be met by MyFloridaRx.com is Consumer 3, who is prescribed Fosamax (for osteoporosis) and hydrocodone/acetaminophen (for chronic back pain). Of the 70 pharmacies in Hialeah, only one had a price listed for Fosamax, while none had a price for hydrocodone/acetaminophen, which was excluded from the Web site because of concerns about potential abuse. If Consumer 3 had widened her search for Fosamax to all of Miami-Dade County, she could have traveled approximately 8 miles from central Hialeah to the nearest pharmacy in Miami and saved nearly $100 on her prescription. The sparse data for Fosamax on MyFloridaRx.com points to one of the weaknesses of using Medicaid transactions as a data source: Certain population subgroups, such as women in their 50s, are underrepresented in the Medicaid population; consequently, the drugs they commonly take also will be underrepresented.

Of the five consumers profiled, only one consumer would find her information needs substantially met by using MyFloridaRx.com. The four other consumers have at least one medication for which the Web site provides little or no price information. This finding is consistent with results of the Top 10 drug analysis, which found that missing price information is a serious issue that substantially limits the Web site’s usefulness.

Price Accuracy: Top 10 Drug List. Telephone calls were made to a subset of pharmacies to spot check how well the prices listed on MyFloridaRx.com for the Top 10 drugs matched the prices quoted by pharmacies to callers identifying themselves as cash-paying customers. The results of this analysis showed that MyFloridaRx.com prices were generally quite accurate for chain drugstores and for pharmacies in supermarkets and mass-market retailers. For independent pharmacies, however, the prices quoted by phone differed from the MyFloridaRx.com prices for all the cases checked. Where prices differed, the telephone quote usually was almost always lower than the published price. While this analysis was only a random spot check and was not meant to be definitive, there is a pattern suggesting that drug prices posted for independent pharmacies are substantially less reliable than those for major retailers. This discrepancy may result from drug prices fluctuating more frequently, and perhaps price reporting errors occurring more often, at independent pharmacies as compared to larger retailers.

In addition to these random price checks, selected outlier prices were checked in the suburban Leon County market. For three of the Top 10 drugs, prices listed on MyFloridaRx.com for one pharmacy were so high (10 to 30 times the median price) that they appeared to be data errors. Indeed, telephone calls to that pharmacy confirmed that the usual and customary prices offered by the pharmacy were much lower than those reported on MyFloridaRx.com and were, in fact, lower than the median prices for those drugs. In a follow-up interview, state Medicaid agency staff confirmed that the Web site does not currently have a system for identifying data outliers and verifying the underlying price data. As a result, it is not clear whether the wrong prices posted on the Web site resulted from reporting errors by the pharmacy or data calculation errors by the state Medicaid agency.

Price Variation: Top 10 Drug List. The substantial degree of missing price data on MyFloridaRx.com, along with the existence of price data outliers, means that it is not possible to use the Web site to assess the extent of drug price variations in a definitive manner. Instead, an attempt was made to examine different dimensions of price variation to the extent possible given the incomplete price data.

First, the available price data for the Top 10 drugs were examined to assess whether there were any discernible patterns in median prices and price ranges across markets. Some drugs (e.g., Synthroid) had relatively modest price dispersion, while others (e.g., lisinopril) showed a much broader price range across pharmacies. One pattern observed was that rural Putnam County tended to have lower median prices and smaller price ranges than the urban Hialeah and suburban Leon County markets. This observation, however, may not apply to drug prices beyond the Top 10 list, and may not be generalized to markets beyond these three specific areas.

Second, an examination was made of whether pharmacies tended to be consistently low-priced or high-priced relative to local competitors or whether their price rankings fluctuated across drugs. Again, it was not possible to conduct this analysis in a definitive way, given the missing data. Instead, a subset of Hialeah pharmacies that had relatively complete price data for the Top 10 drugs was created (defined as having prices for at least seven drugs). The pharmacies were then ranked by quartile based on their prices for each drug relative to the prices of other pharmacies. This analysis found that pharmacies were not consistently high- or low-priced relative to others in the market. Instead, pharmacies that were in the lowest price bracket for some drugs tended to be in the highest price bracket for others. This finding is consistent with previous research, which found that retail pharmacies in upstate New York markets tended not be consistently high- or low-priced relative to local competitors.9 A key implication of this finding is that savings for consumers inclined to fill multiple prescriptions at a single pharmacy will be limited.

The analysis described in this study is only a snapshot of one moment in time; it does not examine what may have happened to average price levels, and extent of price dispersion, over time. Managers of MyFloridaRx.com at Florida’s Agency for Health Care Administration did conduct an analysis comparing price spreads for certain drugs at two moments in time: at the time of the Web site’s launch and approximately six months later. The state’s analysis focused on drugs that showed a broad price range in the pre-launch period and found that this price range had narrowed substantially in the post-launch period. MyFloridaRx.com managers concluded that the “sunshine” effect of seeing their prices made public on the Web site caused high-priced pharmacies to lower their prices considerably, thus yielding significant benefits to consumers. It is important to note some important caveats to that conclusion, however: (1) The posted prices on MyFloridaRx.com do not represent actual transaction prices paid by consumers, so it is not possible to quantify any savings that consumers may have realized; (2) As noted earlier, MyFloridaRx.com does not have a system for identifying and removing data outliers—the high prices reported in the pre-launch period may have been data errors that later were corrected in subsequent reporting periods; and (3) The analysis did not examine what happened to price ranges for those drugs in other markets (without price comparison Web sites) outside of Florida, leaving open the possibility that external factors—rather than the price transparency initiative itself—may have been responsible for reductions in price dispersion across all markets.

Usability Features of MyFloridaRx.com. Compared to some other states’ Web sites, MyFloridaRx.com’s search capabilities are not as flexible and powerful: It does not allow consumers to specify a radius-distance search area or conduct simultaneous price searches for multiple drugs. The site also does not contain information on local pharmacy price matching and generic discount lists. Finally, MyFloridaRx.com does not report the date each price was obtained; however, pharmacy contact information is provided for consumers to call to verify prices.

Compared to other states, MyFloridaRx.com offers relatively more information display features that improve the usability of the Web site, including the ability to sort price tables, export price tables as spreadsheets, and link to maps of pharmacy locations. Finally, MyFloridaRx.com is also one of the only state Web sites available in a Spanish-language version.

Back to Top

Policy Implications

![]() he gaps in available price data at MyFloridaRx.com suggest that a drug price comparison initiative relying on Medicaid claims data inevitably will be subject to incomplete price information. As noted above, some states using Medicaid data for their drug price comparison Web sites have attempted to reduce data omissions by expanding the data-reporting period, but this approach lessens the timeliness and, consequently, the accuracy of the price data. When consumers compare prices using Web sites whose data reporting periods are extended over a long period, they may be making an apples to oranges comparison, comparing a recent price at one pharmacy with a much older price at another.

he gaps in available price data at MyFloridaRx.com suggest that a drug price comparison initiative relying on Medicaid claims data inevitably will be subject to incomplete price information. As noted above, some states using Medicaid data for their drug price comparison Web sites have attempted to reduce data omissions by expanding the data-reporting period, but this approach lessens the timeliness and, consequently, the accuracy of the price data. When consumers compare prices using Web sites whose data reporting periods are extended over a long period, they may be making an apples to oranges comparison, comparing a recent price at one pharmacy with a much older price at another.

An alternative approach to providing price data for drug comparison Web sites—one that has been considered by policy makers in several states but adopted by none to date—is to require pharmacies to submit prescription drug price lists on a regular, frequent basis (e.g., every month) to a state agency, which would post these on the drug price comparison Web site. A chief architect of the MyFloridaRx.com program remarked that it had been an oversight to omit mandated price-list reporting from the 2004 legislation that authorized the Web site, and that, in retrospect, that approach would have provided substantially more complete and useful price information for consumers than the use of Medicaid claims data. Whenever mandated price-list reporting has been proposed, it has faced strong resistance from retail pharmacy associations, which claim that the reporting burden would be heavy. Some experts, however, suggest that this burden is overstated, given that almost all prescription drug claims already are submitted electronically, so the same infrastructure could be used to transmit price lists electronically. It may be that many retailers prefer not have price transparency tools provided to consumers and are simply using reporting burden as the publicly acceptable argument to avert the introduction of those tools.

With the advent of online pharmacies in recent years, consumer shopping for prescription drugs need no longer be restricted to pharmacies located within a certain distance from a consumer’s home or workplace. Consumer Reports notes that U.S.-based online pharmacies “generally sell drugs for less, sometimes substantially less (35% or more)” than brick-and-mortar retail pharmacies.10 To date, no state government has provided consumers with price comparisons from these online pharmacies, but commercial initiatives such as DestinationRx.com and Pillbot.com have done so. For price queries on common drugs, these sites report a wide range of price quotes from online pharmacies—from as few as one to as many as six quotes. States seeking to provide consumers with online pharmacy price comparisons may find it easy to provide links to these commercial sites from state-hosted Web sites.

A brief review of these commercial price comparison sites, however, found that the price quotes they provide sometimes did not match the prices obtained directly from the online pharmacies’ Web sites. As a result, states may prefer not to rely on these commercial sites, but instead to vet online pharmacies themselves and to provide price comparisons from these online pharmacies directly to consumers as part of the state’s price transparency initiative. Even consumers who choose to purchase their prescriptions locally may benefit from using such a Web site, as they will have benchmark prices against which to compare local prices.

U.S.-based online pharmacies are not the only Web sites from which consumers can purchase prescription medications. Policy debates and media coverage in recent years have highlighted the fact that brand-name drugs are often available at substantial savings from pharmacies based in Canada, the United Kingdom and other countries, compared to any type of pharmacy in the U.S. Buying prescription drugs from any foreign country except Canada is technically illegal, and the Canadian exemption applies only to drug purchases made in person, not to drug purchases from Canadian Web sites. However, U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents currently are not enforcing this law; the agency is not seizing packages from Canadian pharmacies if they contain a 90-day supply or less and are for individual use.11

Despite the fact that Congress has not legalized foreign drug purchases, some states already have undertaken initiatives to facilitate such purchases by state employees and other state residents. Minnesota, Wisconsin and New Hampshire are among the states that have inspected and certified Canadian Web sites that they consider reliable for online prescription transactions; these states have then provided links to these Canadian pharmacies, along with step-by-step ordering instructions, available to consumers via state Web sites.12 Other states have shown interest in following suit. The California law establishing the California Rx Prescription Drug Price Web Site Program (Assembly Bill 2877, September 2006) does not specifically mandate—but leaves open the possibility—that the new Web site will contain information for consumers about ordering from international pharmacies, once those pharmacies have passed review by the state’s Department of Health Services.13

One market development that has dovetailed with states’ efforts to increase price transparency has been the well-publicized initiative by discount retailers, led by Wal-Mart, to provide some generic drugs at low prices (generally $4 for a 30-day supply). Wal-Mart launched the program in Tampa, Fla., in September 2006, and had expanded the program to 49 states by December 2006. Its list of low-priced generics, which initially included approximately 140 drugs (totaling more than 300 formulations), was matched completely by Target and partially by Kmart (which offers 90-day supplies at $15 each). The lists are downloadable from these retailers’ Web sites and available at any of their pharmacy locations.

Some experts questioned the overall usefulness to consumers of the $4 generics programs, asserting that many drugs on the list were older generics that were not commonly prescribed or highly priced in the first place. Other experts disagreed, citing as examples antibiotic, arthritis, asthma and cholesterol medications on the Wal-Mart/Target list that were among the most frequently prescribed medications in their respective drug classes. In September 2007, Wal-Mart added 14 new drugs (totaling nearly 30 formulations) to its $4 generic list—additions that have been matched by Target. The new list includes some popular drugs that have recently come off patent, including terbinafine (the generic form of Lamisil, an antifungal medication) and carvedilol (the generic form of Coreg, a beta blocker used to treat congestive heart failure). An analysis found that the updated Wal-Mart/Target list of $4 generics includes approximately 70 percent of the most commonly prescribed generic drugs in the U.S. today,14 so claims that the list is composed mainly of older, less-used drugs do not appear to be supported.

Wal-Mart officials have indicated that they view state drug price comparison Web sites as an opportunity for them to broaden consumer awareness of their $4 generics program. Currently, however, most state Web sites do not make it easy for consumers to identify which pharmacies offer which drugs at which discounted prices; consumers must search on a drug-by-drug basis, and the low prices would appear only if a Wal-Mart or Target within the search area had sold that drug to a Medicaid patient during the reporting period. Michigan, as noted earlier, is the exception: By presenting a table that clearly lists the exact discounted price offered by each discount retailer for each generic drug, the state’s Web site provides a useful resource to consumers.

States seeking to help consumers find the best retail prices for their prescription medications may need to take a multi-pronged approach to optimize shopping resources for consumers. Because drug price comparison Web sites drawing on Medicaid data inevitably contain large data gaps, states that seek to compare retail prices at local pharmacies may need to consider mandating that each retail pharmacy submit price lists to the state. And, because shopping for medications may be most effective if it is not restricted to local markets, states may want to consider providing the following tools, most of which have been made available by at least one state:

- A table showing which retailers offer which generic drugs at steeply discounted prices.

- A list identifying local pharmacies that offer price matching.

- A user’s guide and price comparison tool for U.S.-based online pharmacies (such as that currently provided by commercial sites such as DestinationRx.com).

- A user’s guide and price comparison tool for Canada-based or other foreign-based online pharmacies, which would be particularly helpful to consumers who need brand-name, as opposed to generic, drugs.

Employing all these approaches together would maximize shopping tools for consumers, but it also would require considerable state resources, particularly if the information is to be kept accurate and up to date. States will need to weigh these costs realistically against the potential savings to consumers. As part of this process, policy makers should consider the types of consumers most likely to seek out and benefit from these information sources; previous research suggests that it is consumers with high levels of education and Internet proficiency who will reap the most benefits.15 These consumers, however, are among those least likely to lack health insurance in the first place.

States also will need to consider whether it makes sense to duplicate other states’ efforts, in cases where the tools being provided are broader in scope than local or statewide (for example, when multiple states are providing comparison tools of online pharmacies). There is nothing to prevent well-informed consumers living anywhere in the U.S. from using, for example, Minnesota’s Web site to help them order brand-name drugs from a set of Canadian pharmacies that have already been vetted by the state of Minnesota. Therefore, states launching initiatives to offer essentially the same information may be expending resources while adding little if any marginal benefit.

Some experts have expressed the view that policy interventions aimed at helping consumers save on their prescription drugs should not be restricted to those that focus on promoting consumer shopping at the retail level. These experts assert that, compared to drug manufacturers, retail pharmacies have relatively little market power to affect the overall prices of prescription drugs, especially for single-source medications. In recognition of this, a few states—California among them—have enacted laws establishing state prescription drug discount programs that seek to leverage the state’s Medicaid purchasing power to obtain discounts from drug manufacturers for state residents who lack drug coverage and fall below certain income thresholds (typically, 3 to 3.5 times the federal poverty level).16 Although each state’s discount program differs somewhat, each program uses a two-step approach: first, the state negotiates with drug manufacturers to obtain discounts (through rebates) for program participants; second, if manufacturers do not agree to sufficient rebates, the state has the authority to remove that manufacturer’s drugs from the state Medicaid program’s preferred drug list. Removal from this list would subject those drugs to prior-authorization requirements, which in turn would reduce sales of those drugs to the Medicaid program.

Among the states with these drug discount initiatives, Maine’s program, Maine Rx Plus, has been regarded as the prototype. Research suggests that Maine’s negotiated discounts with drug manufacturers have resulted in substantial price reductions on some commonly prescribed drugs,17 but negotiations with other manufacturers have stalled. Most of these drug discount programs are still too new for their impact to be assessed, but the interest shown by many states in following Maine’s course suggests that many policy makers see a need to use tools beyond retail-level price transparency and consumer shopping in their efforts to help consumers obtain meaningful price reductions for prescription drugs.

Back to Top

Notes

Back to Top

Data Source

Interviews. HSC researchers conducted interviews with state policy makers, pharmacy industry experts, representatives of consumer advocacy organizations and other stakeholders and experts to discuss their views on pharmacy price transparency issues. In addition, for states with drug price comparison initiatives, HSC contacted state agency staff and private data contractors via e-mail and telephone to gather information about these programs.

Top 10 list of commonly used drugs. A major health insurer provided HSC a list of the 10 drugs with the highest dollar amount expenditures (during the fourth quarter of 2006) for paid pharmacy claims among that insurer’s commercial plans. A physician consultant reviewed the drug list to select a common dosage level and formulation for each drug.

Consumer Profiles. The consumer profiles were developed by a physician consultant to represent different age groups, health conditions and combinations of generic and brand name drugs to capture a range of drug needs. The consumer profiles represent actual patients in the physician consultant’s practice.

MyFloridaRx.com. The Florida Web site, MyFloridaRx.com, is a joint initiative between the Office of the Attorney General, which publishes the price data, and the Agency for Health Care Administration (AHCA), the Medicaid administrator in Florida. On a monthly basis, AHCA calculates the average usual and customary prices for the 100 most commonly used brand-name drugs and their generic substitutes (totaling approximately 650 formulations) for the pharmacies that filled at least one Medicaid prescription for those drugs in that month. According to AHCA, the usual and customary price is comparable to the price paid by an uninsured customer, excluding any drug discounts. Price data were downloaded from MyFloridaRx.com May-July 2007; the prices posted on MyFloridaRx.com were reported by the Web site’s documentation as applying to pharmacy prices during April 2007.

Number of Pharmacies: AHCA staff provided HSC researchers with county-specific counts of the number of pharmacies submitting at least one Medicaid claim containing a usual and customary price during April 2007. These counts were used to calculate the total number of pharmacies in each of the urban, suburban and rural markets examined in this report. The total number of retail pharmacies in each market may be greater than these counts.

Price Accuracy: For drugs on the Top 10 list and consumer profiles that match the formulation on MyFloridaRx.com, the prices reported in this study are exactly as they appear on the Web site.

Definition and Selection of Markets. Price data were analyzed in three markets (urban, suburban, rural) with varying concentrations of pharmacies to assess the extent to which consumers can comparison shop. Each market was constructed using population and land area data (obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau) in conjunction with population density and travel distance criteria based upon Medicare/TRICARE pharmacy access standards (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General, “Retail Pharmacy Participation in Medicare Part D Prescription Drug Plans in 2006”).

- The urban market of Hialeah, Fla., (in Miami-Dade County) was purposively selected because it contains a high number of pharmacies and meets a population density of at least 3,000 individuals per square mile and has a land area that is approximately equal to a travel distance of 2.5 miles from the center of the market. This urban market contains 70 pharmacies.

- The suburban market near Tallahassee (Leon County) was defined by selecting a zip code with a population density of 1,000-3,000 people per square mile, then constructing a radius of 5 miles from that zip code to approximate a reasonable travel distance for a suburban pharmacy consumer. The suburban market encompassed all or part of zip codes: 32301, 32303, 32304, 32309 and 32312. This suburban market includes 29 pharmacies.

- Putnam County was selected as the rural market in this analysis because it is a county with a high proportion of the population living in a rural area. This county’s land area approximates a radius of about 15 miles from the center of the county, which is considered a reasonable travel distance for a rural pharmacy consumer. This rural market contains 11 pharmacies.

Back to Top

Acknowledgement: This research was funded by the California HealthCare Foundation and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org