Health Plans Target Advanced Imaging Services

Cost, Quality and Safety Concerns Prompt Renewed Oversight

Issue Brief No. 118

February 2008

Ann Tynan, Robert A. Berenson, Jon B. Christianson

Faced with double-digit annual increases in the use of advanced imaging services, health plans are stepping up efforts to manage imaging utilization, maintain imaging quality and ensure patient safety, according to findings from the Center for Studying Health System Change’s (HSC) 2007 site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities. Plan strategies range from informing physicians about evidence-based imaging guidelines to requiring prior authorization of services to credentialing physicians and imaging equipment. Mindful of the physician backlash against managed care in the 1990s, plans are instituting requirements they perceive to be less intrusive and burdensome for physicians. Some physicians, however, view the requirements as administratively onerous and obstacles to patient care. Depending on the experience with imaging, plans may expand utilization management to other services with rapid volume increases.

- Health Plans Aim Utilization Controls at High-Cost Imaging Services

- Patient Safety and Quality

- Reducing Imaging Utilization

- Plans Seek to Minimize Intrusion

- Implications

- Notes

- Data Source

Health Plans Aim Utilization Controls at High-Cost Imaging Services

![]() ealth plans are stepping up efforts to manage utilization

of high-cost medical services, particularly advanced imaging services, including

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scans, positron emission

tomography (PET) scans and nuclear cardiology imaging, according to findings

from HSC’s 2007 site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities

(see Data Source). Other services, such as bariatric surgery

and specialty pharmaceuticals—where utilization and costs have grown rapidly—also

are receiving attention. Health plans are targeting selected, high-cost services

for more aggressive utilization management rather than imposing stricter controls

across all services. Plans hope the targeted strategy will help avoid physician

and patient backlash against perceived intrusion on physician autonomy and the

administrative burden associated with utilization control requirements.

ealth plans are stepping up efforts to manage utilization

of high-cost medical services, particularly advanced imaging services, including

magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT) scans, positron emission

tomography (PET) scans and nuclear cardiology imaging, according to findings

from HSC’s 2007 site visits to 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities

(see Data Source). Other services, such as bariatric surgery

and specialty pharmaceuticals—where utilization and costs have grown rapidly—also

are receiving attention. Health plans are targeting selected, high-cost services

for more aggressive utilization management rather than imposing stricter controls

across all services. Plans hope the targeted strategy will help avoid physician

and patient backlash against perceived intrusion on physician autonomy and the

administrative burden associated with utilization control requirements.

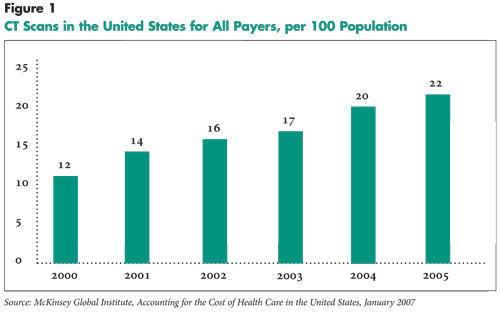

Since 2000, the use of advanced imaging has grown significantly for both commercial health plans and Medicare. The annual growth rate in the number of CT scans performed in the United States per 100 population between 2000 and 2005, for example, was 13 percent, rising from 12 CT scans per 100 people in 2000 to 22 scans per 100 people in 20051 (see Figure 1). For Medicare in particular, the average annual growth rate for CT and MRI scans was 15 percent or higher from 2000 to 2004.2 Reasons for the growth in CT scans include improvements in technology that make them more useful diagnostic tools and a proliferation of the machines.3,4

Back to Top

|

Click here to view this figure as a PowerPoint slide.

Patient Safety and Quality

![]() long with escalating cost pressures resulting from the

rapid growth in imaging utilization, there also are growing concerns about patient

safety and quality of care. Repeated imaging may result from poor quality images

generated by substandard equipment or from inaccurate interpretation of results

by inadequately trained physicians. Nevertheless, repeated use of CT scans,

for example, can expose patients to excessive amounts of radiation, because

these scans generally emit significantly larger amounts of radiation than traditional

X-rays. According to a recent study of CT radiation exposure, a conventional

abdominal X-ray results in at least a 50 times smaller amount of radiation than

an abdominal CT scan.5 The Wall Street Journal also

reported on this trend, revealing that several patients tracked in a managed

care database each had received more than 100 CT scans.6

Recent research theorized a possible link between multiple CT scans and cancer;

two or three chest CT scans expose patients to a similar dose of radiation as

Japanese survivors of atomic bombs, who have a demonstrated increased risk of

dying from cancer.7

long with escalating cost pressures resulting from the

rapid growth in imaging utilization, there also are growing concerns about patient

safety and quality of care. Repeated imaging may result from poor quality images

generated by substandard equipment or from inaccurate interpretation of results

by inadequately trained physicians. Nevertheless, repeated use of CT scans,

for example, can expose patients to excessive amounts of radiation, because

these scans generally emit significantly larger amounts of radiation than traditional

X-rays. According to a recent study of CT radiation exposure, a conventional

abdominal X-ray results in at least a 50 times smaller amount of radiation than

an abdominal CT scan.5 The Wall Street Journal also

reported on this trend, revealing that several patients tracked in a managed

care database each had received more than 100 CT scans.6

Recent research theorized a possible link between multiple CT scans and cancer;

two or three chest CT scans expose patients to a similar dose of radiation as

Japanese survivors of atomic bombs, who have a demonstrated increased risk of

dying from cancer.7

Reduction in radiation exposure may be achieved by the substitution, when appropriate, of other forms of diagnostic testing that do not involve radiation. The American College of Radiology (ACR) developed criteria to help radiologists and other physicians identify the most appropriate tests for more than 200 clinical conditions—including recommendations to avoid scans using radiation when others, such as MRI and ultrasound, which do not use radiation, may be better for a particular condition. In response to recent concerns about radiation exposure, the ACR proposed additional activities to reduce radiation exposure, which are summarized in a white paper by the ACR Blue Ribbon Panel on Radiation Dose.8

There also are concerns that physician ownership of imaging equipment is resulting in overutilization. Some health plans believe that physicians view imaging as a profitable revenue source because used imaging equipment can be purchased cheaply or obtained through lease and other arrangements without significant upfront costs. Recent analysis of physician self-referral arrangements for imaging found that nearly a third of providers submitting claims for MRI scans and about a fifth of providers submitting bills for CT or PET scans either owned imaging equipment or were involved in time-share or pay-per-click arrangements.9 Under a time-share arrangement, a physician rents an imaging center, usually within the same building as the practice, for a certain day of the week or part of a day, and refers patients to that center; the physician bills the insurer for those scans. Under a per-click arrangement, the referring physician sends patients to a designated imaging provider and pays that provider a set fee per imaging study; the referring physician then bills the insurer for each scan and profits from the difference between the amount reimbursed by the insurer and the per-click fee. These types of arrangements are designed to avoid violations of the federal law—known as Stark II—that prohibits many physician self-referral arrangements.

Back to Top

Reducing Imaging Utilization

![]() lthough in 2007 Medicare capped reimbursement rates for imaging performed in physician offices and diagnostic imaging centers, some health plan respondents said that they haven’t reduced rates for imaging services because of concerns that high-quality providers would drop out of networks, thereby limiting member choice of providers. Instead plans are pursuing strategies ranging from physician feedback and education to more intensive approaches, such as prior notification, prior authorization, and credentialing of physicians and equipment. Health plans often use radiology management vendors to identify opportunities to improve the efficiency and quality of imaging services. In some cases, plans are acquiring vendors—WellPoint, for example, recently acquired American Imaging Management.

lthough in 2007 Medicare capped reimbursement rates for imaging performed in physician offices and diagnostic imaging centers, some health plan respondents said that they haven’t reduced rates for imaging services because of concerns that high-quality providers would drop out of networks, thereby limiting member choice of providers. Instead plans are pursuing strategies ranging from physician feedback and education to more intensive approaches, such as prior notification, prior authorization, and credentialing of physicians and equipment. Health plans often use radiology management vendors to identify opportunities to improve the efficiency and quality of imaging services. In some cases, plans are acquiring vendors—WellPoint, for example, recently acquired American Imaging Management.

A few health plans have emphasized working collaboratively with physicians to decrease unnecessary imaging utilization. They use claims data to analyze physicians’ practice patterns and identify patterns of questionable use by individual physicians. Plans then provide information to physicians to initiate discussions about appropriate imaging use. Some plans provide network physicians with guidance on imaging appropriateness, generally in the form of evidence-based guidelines developed by professional societies like the American College of Radiology and the American College of Cardiology.

A national plan in Miami uses an imaging vendor to allow physicians to consult radiologists and radiology subspecialists about the appropriateness of imaging tests before ordering the tests. One health plan in Phoenix, for example, reported success in reducing the use of high-cost nuclear testing by providing prescribing cardiologists with data on their utilization patterns and asking physicians to use a checklist before deciding what diagnostic tests to order. Through this process, cardiologists are asked to explain why a simpler and less expensive test, such as a treadmill stress test, would not be adequate. According to a plan respondent, targeted cardiologists did begin using treadmill stress tests in many cases, obviating the need for the more expensive nuclear test.

Among health plans reporting some type of utilization management initiatives, most required prior notification or prior authorization. Prior notification only requires physicians to notify the health plan before a patient undergoes an imaging study. Health plans using this approach believe prior notification encourages physicians to select the most appropriate studies based on individual patient’s clinical circumstances. Almost all health plans that reported using prior notification emphasized their desire to collaborate with physicians rather than simply deny or limit imaging services.

Prior authorization—also called precertification or preauthorization—requires physicians to request and receive approval before conducting imaging studies; lacking such approval, health plans typically deny payment to the provider performing the imaging study, even though a different provider may have ordered the study. A Cleveland health plan, for example, instituted a prior-authorization program for advanced imaging studies after observing an annual 20 percent increase in utilization. After requiring prior authorization, the plan saw a large reduction in the growth rate of advanced imaging utilization, while having a denial rate of only 1.5 percent. According to a plan respondent, “We’re not saying ‘No’ that much, but because people have to now justify what difference the test is going to make, they aren’t requesting it as much.”

Credentialing—also called privileging or certifying—of imaging equipment and of physicians who interpret imaging studies is another strategy used by a relatively smaller number of health plans but being contemplated by others. Credentialing requirements limit the number of service sites and physicians that the plan will reimburse for advanced imaging studies. Credentialing of imaging equipment means that qualified professionals regularly inspect the equipment to ensure that it is functioning properly and meets certain standards developed by medical professional societies and accreditation organizations.

Plan respondents using this approach were concerned that physicians are installing outdated, used or otherwise inadequate imaging equipment in their practices to generate additional revenue. The concern is that such equipment can produce substandard image quality and, thus, generate repeat imaging, which leads to higher utilization and costs and contributes to patient safety problems. As one Indianapolis plan respondent described the situation, “Some doctors found their equipment on e-Bay. Those are just cash machines some physicians have put into their practices that shouldn’t be in service.”

In addition to credentialing of imaging equipment, plans also credential physicians performing and interpreting imaging studies. They require physicians to meet certain training and education standards to be included in the plan’s network and receive payment for imaging services. This reflects concerns that some physicians with in-house imaging equipment are insufficiently trained in radiology to interpret testing results accurately. These concerns are underscored by a reported shift in the performance of imaging services from hospitals and large radiology groups, which have institutional standards for testing and interpretation, to physicians’ offices where generally there is less oversight of quality. A health plan in Indianapolis partnered with a radiology management vendor to create certification standards that consider the type and age of the equipment and the qualifications of the physicians who interpret imaging studies. The plan intends to designate physicians who score well and have lower costs as “preferred physicians” in communications with members.

As health plans develop credentialing programs for imaging equipment and advanced imaging performed in physicians’ offices, Medicare may look to the private sector for utilization management guidance. The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC), a Congressional entity that advises on Medicare payment policy, urged the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to look to private health plans for ways to help manage the growth and quality of imaging services, specifically pointing to private health plans’ use of credentialing as a utilization control tool. MedPAC recommended that CMS set standards for physicians who bill Medicare for performing and interpreting diagnostic imaging studies, citing the need to control Medicare spending and enhance the quality of care.10

Back to Top

Plans Seek to Minimize Intrusion

![]() n the wake of the managed care backlash, health plan respondents said they are trying to use less burdensome tactics to control imaging utilization. In an effort to more closely target the utilization controls to physicians or imaging studies most at risk for inappropriate or unnecessary use, some health plans now selectively apply utilization management requirements. For example, a Syracuse health plan requires prenotification only by primary care physicians ordering PET scans; prenotification is not required for particular specialists. Other health plans reported that they are exempting, or “gold carding,” certain physicians or groups of physicians from utilization management requirements based on their prior performance. The preauthorization requirements instituted by a Boston plan vary by physician and are based on the physician’s track record, as well as the specific type of imaging study being ordered. One Miami plan waives precertification requirements for physicians who have been designated by the plan as meeting standards for efficiency and quality of care.

n the wake of the managed care backlash, health plan respondents said they are trying to use less burdensome tactics to control imaging utilization. In an effort to more closely target the utilization controls to physicians or imaging studies most at risk for inappropriate or unnecessary use, some health plans now selectively apply utilization management requirements. For example, a Syracuse health plan requires prenotification only by primary care physicians ordering PET scans; prenotification is not required for particular specialists. Other health plans reported that they are exempting, or “gold carding,” certain physicians or groups of physicians from utilization management requirements based on their prior performance. The preauthorization requirements instituted by a Boston plan vary by physician and are based on the physician’s track record, as well as the specific type of imaging study being ordered. One Miami plan waives precertification requirements for physicians who have been designated by the plan as meeting standards for efficiency and quality of care.

While some physicians applaud these kinds of plan initiatives to lessen the burden of imaging utilization requirements, other physicians are dissatisfied with plan efforts. Some physicians acknowledged that the opportunity to file requests for prior approval of imaging studies electronically reduces the administrative burden and also noted that electronic submission has resulted in fewer denials and less paperwork, especially after they become familiar with the requirements. Other physicians, however, complained that utilization management programs interfere with patient care and impose significant administrative burden on their practices.

Further, some physicians believe that new imaging utilization requirements are ultimately inefficient. For example, a physician in Little Rock has observed the trend of primary care physicians making referrals to specialists instead of taking the time to obtain preauthorization for imaging services. This trend may escalate health care costs because such a pattern generates an additional office visit to get the imaging test performed. A few physicians pointed out that health plans’ imaging utilization management requirements often do not allow same-day testing, creating barriers for patients who have to travel long distances to access specialist services. This raises potential quality of care issues, if imaging services can’t be rendered on a timely basis, and may increase the “time costs” of patients. Physicians also assert that obtaining authorizations and communicating with health plans about imaging consumes considerable staff time in their practices; some physicians reported having to assign one or more staff full time to comply with utilization management requirements, particularly prior authorization.

Back to Top

Implications

![]() espite physician objections to utilization controls for imaging, health plans generally have stood firm because they believe they have the support of employers and that the cost savings and patient safety gains associated with the increased oversight outweigh the potential negative effects. As plans expand imaging management, there is a need for independent evaluations that address not only the magnitude of costs savings from various health plan strategies, but also the magnitude of the costs generated for providers and patients and the implications for patient safety and quality of care.

espite physician objections to utilization controls for imaging, health plans generally have stood firm because they believe they have the support of employers and that the cost savings and patient safety gains associated with the increased oversight outweigh the potential negative effects. As plans expand imaging management, there is a need for independent evaluations that address not only the magnitude of costs savings from various health plan strategies, but also the magnitude of the costs generated for providers and patients and the implications for patient safety and quality of care.

Private health plans’ strategy of managing imaging utilization is relevant to Medicare, which is experiencing the same challenges. While private plans rely on administrative controls more than pricing to control spending, Medicare traditionally has been far less aggressive in trying to control costs through administrative controls, instead opting to reduce payment rates. However, Medicare also could take a lead from the private sector and consider setting standards for providers who bill Medicare for performing and interpreting imaging studies.

Back to Top

Notes

Back to Top

Data Source

Every two years, HSC conducts site visits in 12 nationally representative metropolitan communities as part of the Community Tracking Study to interview health care leaders about the local health care market and how it has changed. The communities are Boston; Cleveland; Greenville, S.C.; Indianapolis; Lansing, Mich.; Little Rock, Ark.; Miami; northern New Jersey; Orange County, Calif.; Phoenix; Seattle; and Syracuse, N.Y. Approximately 500 interviews were conducted between February and June 2007 in the 12 communities with representatives of health plans, hospitals, physician organizations, major employers, benefit consultants, insurance brokers, community health centers, consumer advocates and state and local policy makers. In each community, representatives from at least two of the largest health plans were interviewed. Targeted health plan respondents included the medical director, a marketing executive, and a network executive.

Back to Top

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the

Center for Studying Health System Change.

600 Maryland Avenue, SW, Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 484-5261

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org