Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Insurance Coverage & Costs

Access to Care

Quality & Care Delivery

Health Care Markets

Employers/Consumers

Health Plans

Hospitals

Physicians

Issue Briefs

Data Bulletins

Research Briefs

Policy Analyses

Community Reports

Journal Articles

Other Publications

Surveys

Site Visits

Design and Methods

Data Files

|

Highly Consolidated Market Poses Cost Control Challenges

Lansing, Mich.

Community Report No. 06

Winter 2001

Kelly Devers, Jon B. Christianson, Laurie E. Felland, Suzanne Felt-Lisk, Liza Rudell, J. Lee Hargraves

n October 2000, a team of researchers visited Lansing, Mich.,

to study that community’s health system, how it is changing and the effects of

those changes on consumers. The Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC),

as part of the Community Tracking Study, interviewed more than 85 leaders in the

health care market. Lansing is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two

years through site visits and surveys. Individual community reports are published

for each round of site visits. The first two site visits to Lansing, in 1996 and

1998, provided baseline and initial trend information against which changes are

tracked. The Lansing market includes Ingham, Clinton and Eaton counties. n October 2000, a team of researchers visited Lansing, Mich.,

to study that community’s health system, how it is changing and the effects of

those changes on consumers. The Center for Studying Health System Change (HSC),

as part of the Community Tracking Study, interviewed more than 85 leaders in the

health care market. Lansing is one of 12 communities tracked by HSC every two

years through site visits and surveys. Individual community reports are published

for each round of site visits. The first two site visits to Lansing, in 1996 and

1998, provided baseline and initial trend information against which changes are

tracked. The Lansing market includes Ingham, Clinton and Eaton counties.

One health plan and one hospital system now control much of Lansing’s health care

market. Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM), the dominant plan, covers

about 70 percent of commercially insured individuals. The dominant hospital system,

Sparrow Health System, which was created by the merger of two local hospitals

in 1997, now controls more than 60 percent of the hospital market. It also owns

Lansing’s second major health plan, Physicians Health Plan of Mid-Michigan (PHP).

Recent developments suggest that controlling health

care costs in Lansing’s highly consolidated market may be

challenging. Since 1998, employers have been hit with double-digit

health plan premium increases and have responded

only modestly. Other important developments include:

- Hospitals have expanded some clinical services and have

negotiated payment increases from health plans.

- Controversies over freestanding ambulatory surgery

centers (ASCs) have reignited.

- Physicians have adopted strategies to increase their

leverage with plans and hospitals.

- The county health department has continued to lead

efforts to improve care and coverage for the uninsured.

Hospitals Compete Aggressively in Certain Clinical Service Lines

ince 1998, Lansing’s two hospital systems-

Sparrow Health System and the

Ingham Regional Medical Center (IRMC)-

have invested significant resources to

build new tertiary care facilities and to add

or expand clinical service lines. The

expansions are targeted at gaining community

recognition as the highest-quality,

"brand-name" hospital to build loyalty

and enhance profitability.

Sparrow, which had started a cardiovascular surgery program to compete with IRMC,

recently added a Level I trauma unit and a neurosurgical care unit. With an infusion

of capital from its parent organization, McLaren Health Care Corporation, IRMC

added a $21 million women and children’s center to compete with Sparrow in obstetrics/gynecology

and pediatrics to attract younger, middle-class families. IRMC also recently established

the Great Lakes Cancer Institute, a joint venture with Michigan State University

(MSU) to enhance cancer research, services and teaching programs. The arrangements

also will move MSU’s clinical faculty practice and oncology fellowship program

from Sparrow to IRMC. Sparrow has mounted an aggressive advertising campaign to

market its new and improved facilities and services to the community, and IRMC

is expected to launch similar efforts. According to respondents, Sparrow is now

regarded as the premier hospital in the community, but IRMC has advanced in recent

years to become a more formidable competitor.

The increased competition between

Sparrow and IRMC in clinical services

was viewed positively by most respondents,

with a few exceptions. Most of those interviewed

considered the new or enhanced

services valuable to the community,

noting that competition between the two

hospital systems extends to outreach, prevention

and charity care. On the other

hand, some respondents were concerned

about the long-term effects of service

competition on costs and access to more

basic services. ince 1998, Lansing’s two hospital systems-

Sparrow Health System and the

Ingham Regional Medical Center (IRMC)-

have invested significant resources to

build new tertiary care facilities and to add

or expand clinical service lines. The

expansions are targeted at gaining community

recognition as the highest-quality,

"brand-name" hospital to build loyalty

and enhance profitability.

Sparrow, which had started a cardiovascular surgery program to compete with IRMC,

recently added a Level I trauma unit and a neurosurgical care unit. With an infusion

of capital from its parent organization, McLaren Health Care Corporation, IRMC

added a $21 million women and children’s center to compete with Sparrow in obstetrics/gynecology

and pediatrics to attract younger, middle-class families. IRMC also recently established

the Great Lakes Cancer Institute, a joint venture with Michigan State University

(MSU) to enhance cancer research, services and teaching programs. The arrangements

also will move MSU’s clinical faculty practice and oncology fellowship program

from Sparrow to IRMC. Sparrow has mounted an aggressive advertising campaign to

market its new and improved facilities and services to the community, and IRMC

is expected to launch similar efforts. According to respondents, Sparrow is now

regarded as the premier hospital in the community, but IRMC has advanced in recent

years to become a more formidable competitor.

The increased competition between

Sparrow and IRMC in clinical services

was viewed positively by most respondents,

with a few exceptions. Most of those interviewed

considered the new or enhanced

services valuable to the community,

noting that competition between the two

hospital systems extends to outreach, prevention

and charity care. On the other

hand, some respondents were concerned

about the long-term effects of service

competition on costs and access to more

basic services.

Freestanding Ambulatory Surgery Centers Reignite Controversy

hree freestanding ASCs were started by

physician entrepreneurs between 1996

and 1998, generating controversy over the

role of such ASCs in the provision of

ambulatory surgery services. A March 2000

ruling by Michigan’s state insurance commissioner

reignited that controversy.

The debate about whether to include

freestanding ASCs in commercial plan

networks illustrates the complex issues

raised by facilities that compete to provide

services traditionally provided by hospitals.

Proponents argue that freestanding

ASCs should be given the opportunity to

compete with hospital-based ASCs. More

specifically, they contend that, compared

with hospital-based ASCs, freestanding

ASCs have substantially lower costs and

higher consumer satisfaction and are of

equal or better quality.

Opponents argue that the freestanding

ASCs duplicate hospital capacity, ultimately

resulting in higher total costs. For

this reason, General Motors (GM) has

refused to allow plans serving its employees

to include freestanding ASCs in their networks.

In part because of GM’s position

on this issue, BCBSM also has refused to

contract with these entities. Over the past

two years, however, a successful lawsuit

filed by one of the local ASCs led BCBSM

to include it in its network, although

BCBSM subsequently raised concerns

about the quality of care the center provided,

given its low volume of procedures.

In March 2000, Michigan’s state

insurance commissioner ruled that

BCBSM’s refusal to contract with freestanding

ASCs was based on inequitable

access and quality standards. BCBSM’s

new standards, which may make it easier

for freestanding ASCs to participate in

BCBSM indemnity products, are currently

under review by the commissioner. If these

new criteria result in BCBSM expanding

its contracts with ASCs, the Lansing market

is likely to see increased competition

for ambulatory surgery services in the

years ahead, which will help test theories

of ASCs’ implications for cost, quality

and consumer satisfaction. hree freestanding ASCs were started by

physician entrepreneurs between 1996

and 1998, generating controversy over the

role of such ASCs in the provision of

ambulatory surgery services. A March 2000

ruling by Michigan’s state insurance commissioner

reignited that controversy.

The debate about whether to include

freestanding ASCs in commercial plan

networks illustrates the complex issues

raised by facilities that compete to provide

services traditionally provided by hospitals.

Proponents argue that freestanding

ASCs should be given the opportunity to

compete with hospital-based ASCs. More

specifically, they contend that, compared

with hospital-based ASCs, freestanding

ASCs have substantially lower costs and

higher consumer satisfaction and are of

equal or better quality.

Opponents argue that the freestanding

ASCs duplicate hospital capacity, ultimately

resulting in higher total costs. For

this reason, General Motors (GM) has

refused to allow plans serving its employees

to include freestanding ASCs in their networks.

In part because of GM’s position

on this issue, BCBSM also has refused to

contract with these entities. Over the past

two years, however, a successful lawsuit

filed by one of the local ASCs led BCBSM

to include it in its network, although

BCBSM subsequently raised concerns

about the quality of care the center provided,

given its low volume of procedures.

In March 2000, Michigan’s state

insurance commissioner ruled that

BCBSM’s refusal to contract with freestanding

ASCs was based on inequitable

access and quality standards. BCBSM’s

new standards, which may make it easier

for freestanding ASCs to participate in

BCBSM indemnity products, are currently

under review by the commissioner. If these

new criteria result in BCBSM expanding

its contracts with ASCs, the Lansing market

is likely to see increased competition

for ambulatory surgery services in the

years ahead, which will help test theories

of ASCs’ implications for cost, quality

and consumer satisfaction.

Physicians Move to Increase Leverage with Plans and Hospitals

hysicians in Lansing’s highly consolidated

and increasingly competitive market have

relied on several strategies to maintain

their autonomy and increase their leverage

with plans and hospitals by: (1) consolidating

into larger practice groups; (2)

adopting a more aggressive negotiating

stance with plans; and (3) continuing

their participation in the physician-hospital

organizations (PHOs) of both Sparrow

and IRMC.

Although some larger physician

groups have formed in Lansing in past

years, small single-specialty groups have

been more successful recently in consolidating

than have larger ones. Over the

past two years, there have been a number

of instances in which specialists in solo

practices and very small groups have consolidated

into larger groups of approximately

10 physicians. Meanwhile, two of the three

larger physician groups that had been

growing-Thoracic and Cardiovascular

Institute and Mid-Michigan Physicians-

lost momentum in the drive to grow

because they had to focus on other management

issues related to declining Medicare

reimbursement and developing information

systems to support their practices.

Physician groups also have asserted

themselves recently by demanding changes

in their contracts with health plans. Having

found that extensive risk-sharing arrangements

with plans are unprofitable for

them, most physician groups have shown

little interest in capitated arrangements

(other than for primary care services)

with health plans. Several physician groups

have renegotiated or pulled out of the few

capitated contracts they had. In addition,

physicians have taken steps to improve

their fee-for-service contracts, securing

better contract terms and improved

payment rates.

Finally, physicians have improved

their position compared to local hospitals

as pressure to align exclusively with one

of the two hospitals’ PHOs has waned.

Because PHOs have not become the major

contracting vehicles in the market as anticipated,

hospitals have less leverage to push

for exclusive physician membership. As a

result, physicians have been successful in

maintaining relationships with both

Sparrow and IRMC’s PHOs, reducing

physicians’ dependence on any one hospital. hysicians in Lansing’s highly consolidated

and increasingly competitive market have

relied on several strategies to maintain

their autonomy and increase their leverage

with plans and hospitals by: (1) consolidating

into larger practice groups; (2)

adopting a more aggressive negotiating

stance with plans; and (3) continuing

their participation in the physician-hospital

organizations (PHOs) of both Sparrow

and IRMC.

Although some larger physician

groups have formed in Lansing in past

years, small single-specialty groups have

been more successful recently in consolidating

than have larger ones. Over the

past two years, there have been a number

of instances in which specialists in solo

practices and very small groups have consolidated

into larger groups of approximately

10 physicians. Meanwhile, two of the three

larger physician groups that had been

growing-Thoracic and Cardiovascular

Institute and Mid-Michigan Physicians-

lost momentum in the drive to grow

because they had to focus on other management

issues related to declining Medicare

reimbursement and developing information

systems to support their practices.

Physician groups also have asserted

themselves recently by demanding changes

in their contracts with health plans. Having

found that extensive risk-sharing arrangements

with plans are unprofitable for

them, most physician groups have shown

little interest in capitated arrangements

(other than for primary care services)

with health plans. Several physician groups

have renegotiated or pulled out of the few

capitated contracts they had. In addition,

physicians have taken steps to improve

their fee-for-service contracts, securing

better contract terms and improved

payment rates.

Finally, physicians have improved

their position compared to local hospitals

as pressure to align exclusively with one

of the two hospitals’ PHOs has waned.

Because PHOs have not become the major

contracting vehicles in the market as anticipated,

hospitals have less leverage to push

for exclusive physician membership. As a

result, physicians have been successful in

maintaining relationships with both

Sparrow and IRMC’s PHOs, reducing

physicians’ dependence on any one hospital.

Hospitals Negotiate Small Payment Increases from Plans

aced with declining reimbursement

from Medicare and Medicaid and rapidly

rising costs, Lansing’s hospital systems

have pushed back on commercial health

plan contracts and finally secured small

payment increases after years of considerable

discounts.

Hospitals nationally have confronted

declining Medicare revenues under the

Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997,

and as teaching institutions, Sparrow

and IRMC have experienced additional

declines because of the BBA’s provisions

regarding graduate medical education.

These problems have been compounded

by difficulties in Michigan’s Medicaid

managed care program, including payments

that providers allege are too low

and too slow. At the same time, hospitals

have experienced substantial cost increases

driven by labor shortages, pressure to

acquire new technologies and information

systems and rising inpatient pharmaceutical

costs.

Now that they are the only two hospital

systems, Sparrow and IRMC have

more leverage in their negotiations with

BCBSM and PHP, especially in an environment

where plans must include both

hospital systems in their products to be

successful. This leverage has enabled them

to negotiate higher payment rates from

health plans.

Another response to financial pressures

by Lansing’s hospital systems has been to

cut selected clinical and administrative

services and improve efficiency. IRMC, for

example, eliminated approximately 80

positions by consolidating administrative

functions with its parent organization and

discontinuing services, such as transitional

care units, that the hospital determined

were no longer reimbursed adequately

under Medicare.

Sparrow and IRMC also expect some

relief from financial pressures in the near

future, thanks to the recent restoration of

some Medicare BBA funds and increases

in provider reimbursement rates in

Michigan’s Medicaid managed care program. aced with declining reimbursement

from Medicare and Medicaid and rapidly

rising costs, Lansing’s hospital systems

have pushed back on commercial health

plan contracts and finally secured small

payment increases after years of considerable

discounts.

Hospitals nationally have confronted

declining Medicare revenues under the

Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997,

and as teaching institutions, Sparrow

and IRMC have experienced additional

declines because of the BBA’s provisions

regarding graduate medical education.

These problems have been compounded

by difficulties in Michigan’s Medicaid

managed care program, including payments

that providers allege are too low

and too slow. At the same time, hospitals

have experienced substantial cost increases

driven by labor shortages, pressure to

acquire new technologies and information

systems and rising inpatient pharmaceutical

costs.

Now that they are the only two hospital

systems, Sparrow and IRMC have

more leverage in their negotiations with

BCBSM and PHP, especially in an environment

where plans must include both

hospital systems in their products to be

successful. This leverage has enabled them

to negotiate higher payment rates from

health plans.

Another response to financial pressures

by Lansing’s hospital systems has been to

cut selected clinical and administrative

services and improve efficiency. IRMC, for

example, eliminated approximately 80

positions by consolidating administrative

functions with its parent organization and

discontinuing services, such as transitional

care units, that the hospital determined

were no longer reimbursed adequately

under Medicare.

Sparrow and IRMC also expect some

relief from financial pressures in the near

future, thanks to the recent restoration of

some Medicare BBA funds and increases

in provider reimbursement rates in

Michigan’s Medicaid managed care program.

Health Plans Raise Employers’ Premiums

o cover increased costs and to make

up for losses associated with the insurance

underwriting cycle, Lansing’s two

major health plans-BCBSM and the

Sparrow-sponsored plan, PHP-have

raised employer premiums substantially

in the past two years. Although this is a

national trend, it is especially striking

in Lansing, where premium increases

occurred despite a community-wide

"Save GM" campaign that was trying

to demonstrate to the automobile manufacturer

that Lansing was a good place

to continue to do business-in part

because of the area’s ability to keep

health care costs low. The area’s largest

employers-including GM-were hit

with premium hikes of about 9 percent

in the 1999 contract year and 12 to 15

percent in 2000. Small employers experienced

a wider range of premium increases,

from 10 to 25 percent, with more recent

increases of 20 percent or higher.

While some argue that increased

health plan competition would help

restrain premium increases, this appears

unlikely in Lansing in the foreseeable

future. BCBSM and PHP together account

for the vast majority of the local market

share. The two smaller plans in the Lansing

market (M-Care and Regional Community

Blue) have very small enrollments, perhaps

because they include only one of

Lansing’s two hospital systems (IRMC)

in their networks.

Furthermore, one of the two Lansing

hospitals is said by some respondents to

quote other potential health plan entrants

"unreasonably high" rates for hospital

services, making it extremely difficult for

new plans to enter and compete successfully

in the market. (The hospital maintains

that the higher rates these respondents

quote reflect smaller discounts because of

low volume.) The fact that Lansing has

fewer than 500,000 residents also limits

its attractiveness to large national plans.

Competition has failed to develop in

Lansing’s public sector managed care programs,

as well. The only Medicare managed

care provider is BCBSM’s subsidiary, Blue

Care Network, whose enrollment has

stabilized at about 6,800 members. PHP

decided not to enter Lansing’s Medicare

risk market, concluding that it was unlikely

to be profitable.

The Medicaid managed care market

is dominated by just two plans: PHP

(Sparrow’s affiliated health plan) and

McLaren (IRMC’s affiliated health plan).

A third Medicaid-only health plan (The

Wellness Plan) withdrew from the

Medicaid managed care market in

November 1999, after its contracts with

IRMC and Sparrow were canceled. Two

other Medicaid-only plans (Health Plan

of Michigan and Community Choices)

entered the market anticipating PHP’s

complete withdrawal from the program

but are unlikely to remain because they

have no provider networks and may have

difficulty obtaining one given that both

Sparrow and IRMC have their own

affiliated plans. o cover increased costs and to make

up for losses associated with the insurance

underwriting cycle, Lansing’s two

major health plans-BCBSM and the

Sparrow-sponsored plan, PHP-have

raised employer premiums substantially

in the past two years. Although this is a

national trend, it is especially striking

in Lansing, where premium increases

occurred despite a community-wide

"Save GM" campaign that was trying

to demonstrate to the automobile manufacturer

that Lansing was a good place

to continue to do business-in part

because of the area’s ability to keep

health care costs low. The area’s largest

employers-including GM-were hit

with premium hikes of about 9 percent

in the 1999 contract year and 12 to 15

percent in 2000. Small employers experienced

a wider range of premium increases,

from 10 to 25 percent, with more recent

increases of 20 percent or higher.

While some argue that increased

health plan competition would help

restrain premium increases, this appears

unlikely in Lansing in the foreseeable

future. BCBSM and PHP together account

for the vast majority of the local market

share. The two smaller plans in the Lansing

market (M-Care and Regional Community

Blue) have very small enrollments, perhaps

because they include only one of

Lansing’s two hospital systems (IRMC)

in their networks.

Furthermore, one of the two Lansing

hospitals is said by some respondents to

quote other potential health plan entrants

"unreasonably high" rates for hospital

services, making it extremely difficult for

new plans to enter and compete successfully

in the market. (The hospital maintains

that the higher rates these respondents

quote reflect smaller discounts because of

low volume.) The fact that Lansing has

fewer than 500,000 residents also limits

its attractiveness to large national plans.

Competition has failed to develop in

Lansing’s public sector managed care programs,

as well. The only Medicare managed

care provider is BCBSM’s subsidiary, Blue

Care Network, whose enrollment has

stabilized at about 6,800 members. PHP

decided not to enter Lansing’s Medicare

risk market, concluding that it was unlikely

to be profitable.

The Medicaid managed care market

is dominated by just two plans: PHP

(Sparrow’s affiliated health plan) and

McLaren (IRMC’s affiliated health plan).

A third Medicaid-only health plan (The

Wellness Plan) withdrew from the

Medicaid managed care market in

November 1999, after its contracts with

IRMC and Sparrow were canceled. Two

other Medicaid-only plans (Health Plan

of Michigan and Community Choices)

entered the market anticipating PHP’s

complete withdrawal from the program

but are unlikely to remain because they

have no provider networks and may have

difficulty obtaining one given that both

Sparrow and IRMC have their own

affiliated plans.

Employers Take Modest Steps in Response to Premium Increases

ansing employers’ responses to premium

increases by health plans have been relatively

modest. The primary strategies used

by employers to limit premium increases

are modifying pharmacy benefits, increasing

cost sharing by employees for some

health maintenance organization (HMO)

services and requiring higher deductibles

in indemnity plans offered to employees.

For the most part, Lansing’s employers

have been absorbing the premium increases.

Several factors may account for this

muted response. First, given the strong

union presence and tight labor market in

Lansing, employees expect relatively comprehensive

health insurance coverage with

limited cost sharing for premiums and broad

choice of providers. About 25 percent of

those with commercial health insurance

coverage in Lansing are enrolled in traditional

indemnity products-a much higher

percentage than the national average. Of

those enrolled in managed care options,

most employees select preferred provider

organizations (PPOs) or point-of-service

(POS) products that offer less restrictive

access to providers than do traditional HMOs.

Second, collective efforts by employers

to reduce cost and monitor quality through

the Capital Area Health Alliance (CAHA)-

a coalition comprising all major stakeholders

in the local health care system-were discontinued

three years ago after the public

release of hospital cost information triggered

providers’ concerns. In the absence

of this information, employers’ collective

efforts to contain costs and improve quality

have been seriously constrained.

Third, Lansing’s three largest

employers-GM, the Michigan state

government and MSU-have adopted

national or statewide purchasing strategies

that shape their view of the Lansing market.

For example, GM views Lansing as a

good place to do business from a health

care benefit standpoint, compared to Flint

and other places where GM plants are

located. GM is also an active member of

the Leapfrog Group, a national coalition of

large employers focusing on improving

patient safety, and reportedly is working

with Lansing hospitals to develop initiatives

to reduce medication errors, a key patient

safety priority identified by Leapfrog.

Statewide needs and concerns similarly

shape the state government’s and university’s

perspectives on health care purchasing

in Lansing.

Finally, the few mid-sized and many

small employers in Lansing have little

clout in negotiations with plans. Given

limited plan options, these employers

typically do not switch health plans in

response to price increases-and even if

they do switch, Lansing’s other plans

apparently do not compete aggressively

for their business. At the same time,

employers have concluded that direct contracting

with providers is unlikely to result

in substantial savings. Small businesses in

Lansing purchase health insurance through

various associations in an effort to improve

their negotiating leverage, but these initiatives

have met with limited success. ansing employers’ responses to premium

increases by health plans have been relatively

modest. The primary strategies used

by employers to limit premium increases

are modifying pharmacy benefits, increasing

cost sharing by employees for some

health maintenance organization (HMO)

services and requiring higher deductibles

in indemnity plans offered to employees.

For the most part, Lansing’s employers

have been absorbing the premium increases.

Several factors may account for this

muted response. First, given the strong

union presence and tight labor market in

Lansing, employees expect relatively comprehensive

health insurance coverage with

limited cost sharing for premiums and broad

choice of providers. About 25 percent of

those with commercial health insurance

coverage in Lansing are enrolled in traditional

indemnity products-a much higher

percentage than the national average. Of

those enrolled in managed care options,

most employees select preferred provider

organizations (PPOs) or point-of-service

(POS) products that offer less restrictive

access to providers than do traditional HMOs.

Second, collective efforts by employers

to reduce cost and monitor quality through

the Capital Area Health Alliance (CAHA)-

a coalition comprising all major stakeholders

in the local health care system-were discontinued

three years ago after the public

release of hospital cost information triggered

providers’ concerns. In the absence

of this information, employers’ collective

efforts to contain costs and improve quality

have been seriously constrained.

Third, Lansing’s three largest

employers-GM, the Michigan state

government and MSU-have adopted

national or statewide purchasing strategies

that shape their view of the Lansing market.

For example, GM views Lansing as a

good place to do business from a health

care benefit standpoint, compared to Flint

and other places where GM plants are

located. GM is also an active member of

the Leapfrog Group, a national coalition of

large employers focusing on improving

patient safety, and reportedly is working

with Lansing hospitals to develop initiatives

to reduce medication errors, a key patient

safety priority identified by Leapfrog.

Statewide needs and concerns similarly

shape the state government’s and university’s

perspectives on health care purchasing

in Lansing.

Finally, the few mid-sized and many

small employers in Lansing have little

clout in negotiations with plans. Given

limited plan options, these employers

typically do not switch health plans in

response to price increases-and even if

they do switch, Lansing’s other plans

apparently do not compete aggressively

for their business. At the same time,

employers have concluded that direct contracting

with providers is unlikely to result

in substantial savings. Small businesses in

Lansing purchase health insurance through

various associations in an effort to improve

their negotiating leverage, but these initiatives

have met with limited success.

Care and Coverage Improves for the Uninsured

ansing enjoys an uninsurance rate that is

significantly below the national average,

and the Ingham County Health Department

continues to lead collaborative efforts to

improve care and coverage for individuals

without health insurance. In addition to

leading Medicaid and MIChild (the State

Children’s Health Insurance Program)

outreach efforts, the county health department

administers the Ingham Health Plan

(IHP)-a managed care program for

the uninsured.

Under the IHP, the Ingham County

Health Department provides and coordinates

outpatient preventive, primary,

specialty and ancillary care services for

low-income, uninsured adults and

children who are not eligible for public

insurance programs. Already noted for its

success at the time of the previous site

visit, IHP has continued to grow over the

past two years. Currently, it serves approximately

11,500 people-an increase of more

than 50 percent since 1998. Through a new

contract with the MSU faculty practice,

IHP also has expanded access to outpatient

services. A pharmaceutical program created

by IHP in October 2000 obtains volume

discounts of 20 percent on medications

for low-income seniors.

On the horizon are further expansions

of IHP to reach more of the community’s

working poor. Approximately 60 percent

of the program’s current participants are

employed but do not have employer-sponsored

health insurance coverage,

either because their employers do not offer

it or because they cannot afford the premiums.

To reach more of the working poor

who do not have insurance, IHP is planning

to implement a new "third-share"

program in which employers and employees

each contribute one-third of the cost of

premiums, and IHP subsidizes the remaining

one-third. The total premium for

individual coverage is expected to be

approximately $120 per month, making the

monthly cost for individuals roughly $40.

IHP is funded through a combination

of local, state and federal matching

funds-generated by a special Medicaid

disproportionate share hospital (DSH)

payment program-that flow through

IRMC. Despite IRMC’s substantial commitment

to IHP, the special DSH funds

available to the program were limited when

IRMC was the sole hospital participant.

However, after resolving some initial objections,

Sparrow recently decided to participate

in IHP as well, which should bolster

the plan’s funding base and help to support

continued expansion of the number of

people served and providers participating

in the program. New regulations that curtail

the use of federal Medicaid matching

funds for certain services raised concern

about IHP’s continued ability to draw on

DSH funds for support, but state administrators’

interpretation of the ruling is that

the funding stream is secure at this time. ansing enjoys an uninsurance rate that is

significantly below the national average,

and the Ingham County Health Department

continues to lead collaborative efforts to

improve care and coverage for individuals

without health insurance. In addition to

leading Medicaid and MIChild (the State

Children’s Health Insurance Program)

outreach efforts, the county health department

administers the Ingham Health Plan

(IHP)-a managed care program for

the uninsured.

Under the IHP, the Ingham County

Health Department provides and coordinates

outpatient preventive, primary,

specialty and ancillary care services for

low-income, uninsured adults and

children who are not eligible for public

insurance programs. Already noted for its

success at the time of the previous site

visit, IHP has continued to grow over the

past two years. Currently, it serves approximately

11,500 people-an increase of more

than 50 percent since 1998. Through a new

contract with the MSU faculty practice,

IHP also has expanded access to outpatient

services. A pharmaceutical program created

by IHP in October 2000 obtains volume

discounts of 20 percent on medications

for low-income seniors.

On the horizon are further expansions

of IHP to reach more of the community’s

working poor. Approximately 60 percent

of the program’s current participants are

employed but do not have employer-sponsored

health insurance coverage,

either because their employers do not offer

it or because they cannot afford the premiums.

To reach more of the working poor

who do not have insurance, IHP is planning

to implement a new "third-share"

program in which employers and employees

each contribute one-third of the cost of

premiums, and IHP subsidizes the remaining

one-third. The total premium for

individual coverage is expected to be

approximately $120 per month, making the

monthly cost for individuals roughly $40.

IHP is funded through a combination

of local, state and federal matching

funds-generated by a special Medicaid

disproportionate share hospital (DSH)

payment program-that flow through

IRMC. Despite IRMC’s substantial commitment

to IHP, the special DSH funds

available to the program were limited when

IRMC was the sole hospital participant.

However, after resolving some initial objections,

Sparrow recently decided to participate

in IHP as well, which should bolster

the plan’s funding base and help to support

continued expansion of the number of

people served and providers participating

in the program. New regulations that curtail

the use of federal Medicaid matching

funds for certain services raised concern

about IHP’s continued ability to draw on

DSH funds for support, but state administrators’

interpretation of the ruling is that

the funding stream is secure at this time.

Issues to Track

ising premiums, limited plan competition

and increased service competition

observed over the last two years suggest

that controlling health care costs may prove

very difficult for Lansing employers in the

future. Consequently, employees and their

unions may face difficult choices about

health care coverage and benefits. In addition,

state regulators may increasingly face

complex questions about provider capacity

and competition among plans, hospitals

and physicians. As the Lansing market

continues to evolve, it will be important

to track the following questions: ising premiums, limited plan competition

and increased service competition

observed over the last two years suggest

that controlling health care costs may prove

very difficult for Lansing employers in the

future. Consequently, employees and their

unions may face difficult choices about

health care coverage and benefits. In addition,

state regulators may increasingly face

complex questions about provider capacity

and competition among plans, hospitals

and physicians. As the Lansing market

continues to evolve, it will be important

to track the following questions:

- Will hospitals continue to be able to

sustain higher payment rates from

health plans?

- What impact will increased competition

among hospitals and physician

entrepreneurs for select clinical services

have on costs, quality and access to care?

- How will employers respond to rising

premiums, particularly if the economy

slows? What leverage can employers

exert in a highly consolidated market

with a heavily unionized workforce that

expects comprehensive coverage and

provider choice?

- Will the Ingham County Health Department’s planned expansions succeed, and

what impact will they have on coverage and care for the uninsured?

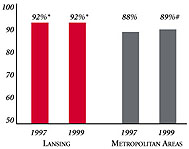

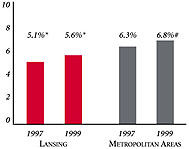

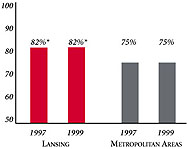

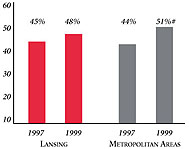

Lansing’s Experience with the Local Health System, 1997 and

1999

Background and Observations

| Lansing Demographics |

| Lansing |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

Population, July 1, 19991

450,789 |

| Population Change, 1990-19992

|

| 4.2% |

8.6% |

| Median Income3 |

| $30,830 |

$27,843 |

| Persons Living in Poverty3 |

| 11% |

14% |

| Persons Age 65 or Older3 |

| 10% |

11% |

Sources:

1. US Bureau of Census, 1999 Community Population Estimates

2. US Bureau of Census, 1990 & 1999 Community Population Estimates

3. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999 |

| Health Insurance Status |

| Lansing |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Persons under Age 65 with No Health Insurance1 |

| 8.2% |

15% |

| Children under Age 18 with No Health Insurance1

|

| 4.0% |

11% |

| Employees Working for Private Firms that

Offer Coverage2 |

| 85% |

84% |

| Average Monthly Premium for Self-Only Coverage

under Employer-Sponsored Insurance2 |

| $183 |

$181 |

Sources:

1. Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-1999

2. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Employer Health Insurance Survey, 1997 |

| Health System Characteristics |

| Lansing |

Metropolitan areas above 200,000 population |

| Staffed Hospital Beds per 1,000 Population1

|

| 2.2 |

2.8 |

| Physicians per 1,000 Population2

|

| 2.1 |

2.3 |

| HMO Penetration, 19973 |

| 41% |

32% |

| HMO Penetration, 19994 |

| 41% |

36% |

Sources:

1. American Hospital Association, 1998

2. Area Resource File, 1998 (includes nonfederal, patient care physicians,

except radiologists, pathologists and anesthesiologists)

3. InterStudy Competitive Edge 8.1

4. InterStudy Competitive Edge 10.1 |

The Community Tracking Study, the major effort of the Center for Studying Health

System Change (HSC), tracks changes in the health system in 60 sites that are

representative of the nation. Every two years, HSC conducts surveys in all 60

communities and site visits in 12 communities. The Community Report series documents

the findings from the third round of site visits. Analyses based on site visit

and survey data from the Community Tracking Study are published by HSC in Issue

Briefs, Data Bulletins and peer-reviewed journals. These publications are

available at www.hschange.org.

Authors of the Lansing Community Report:

Kelly Devers, HSC

Jon B. Christianson, University of Minnesota

Laurie E. Felland, HSC

Sue Felt-Lisk, Mathematica Policy Research, Inc.

Liza Rudell, HSC

J. Lee Hargraves, HSC

Community Reports are published by HSC:

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Site Visits: Cara S. Lesser

Director of Public Affairs: Ann C. Greiner

Editor: The Stein Group

|