Triple Jeopardy: Low Income, Chronically Ill and Uninsured in America

Issue Brief No. 49

February 2002

Marie C. Reed, Ha T. Tu

![]() t least 7.4 million working-age Americans with chronic conditions-such as

diabetes, heart disease and depression-lacked health insurance in 1999, according

to new research findings from the Center for Studying Health System Change

(HSC). Uninsured people with chronic conditions report worse health and more

functional limitations and are three times more likely not to get needed medical

care compared to those who are privately insured. The vast majority of uninsured

people with chronic conditions delayed or did not get needed care because of cost.

About 63 percent of the uninsured with chronic conditions-roughly 4.7 million

Americans-have family incomes below 200 percent of poverty, or about $35,000 a

year for a family of four in 2001. Faced with the triple threat of low income, ongoing

health problems and no health insurance, this group confronts great difficulty

getting and paying for needed care.

t least 7.4 million working-age Americans with chronic conditions-such as

diabetes, heart disease and depression-lacked health insurance in 1999, according

to new research findings from the Center for Studying Health System Change

(HSC). Uninsured people with chronic conditions report worse health and more

functional limitations and are three times more likely not to get needed medical

care compared to those who are privately insured. The vast majority of uninsured

people with chronic conditions delayed or did not get needed care because of cost.

About 63 percent of the uninsured with chronic conditions-roughly 4.7 million

Americans-have family incomes below 200 percent of poverty, or about $35,000 a

year for a family of four in 2001. Faced with the triple threat of low income, ongoing

health problems and no health insurance, this group confronts great difficulty

getting and paying for needed care.

- Chronic Conditions Widespread Among Working-Age Adults

- Uninsured with Chronic Conditions in Worse Health

- Uninsured Far Less Likely to Get Needed Care

- Major Barrier to Care: Cost

- Health Care Services Received

- Policy Implications

- Notes

Chronic Conditions Widespread Among Working-Age Adults

![]() ecause chronic health problems typically increase as people

age, chronic illness often is perceived primarily as a problem of the elderly.

Yet, chronic illness affects more than a third of working-age Americans (18 to

64). In 1999, 37 percent of nonelderly adults, or about 60 million working-age

Americans, reported seeing a doctor in the past two years for at least one chronic

condition, according to HSC’s Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey

(see Methodology).

ecause chronic health problems typically increase as people

age, chronic illness often is perceived primarily as a problem of the elderly.

Yet, chronic illness affects more than a third of working-age Americans (18 to

64). In 1999, 37 percent of nonelderly adults, or about 60 million working-age

Americans, reported seeing a doctor in the past two years for at least one chronic

condition, according to HSC’s Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey

(see Methodology).

Nonelderly adults with chronic conditions are more likely to have health insurance than people without chronic conditions-88 percent vs. 81 percent in 1999.1 At that time, 71 percent of working-age adults with chronic conditions were privately insured; 12 percent were uninsured; 14 percent were covered by Medicare and/or Medicaid; and the remainder had other coverage such as military insurance.

Chronic conditions can range from mild to severe. In some cases, people with chronic conditions experience few limitations, while others cannot perform the normal tasks of daily living without help. Good access to preventive and ongoing medical care for people with chronic conditions can alleviate pain and suffering, improve productivity and minimize future health problems and related costs. For example, people with diabetes who do not receive routine preventive care, including eye exams, foot exams, glucose screenings, cholesterol screenings and blood pressure measurements, are at higher risk for blindness, kidney failure and amputations. And, health insurance coverage plays an important and well-documented role in improving access to medical care.

The findings for this Issue Brief are based on an analysis of the 1998-99 CTS Household Survey. The survey asked respondents aged 18 to 64 whether they had been diagnosed with one of more than 20 chronic conditions and had seen a doctor in the past two years for the condition. The list of chronic conditions includes asthma, diabetes, arthritis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, stroke, hypertension, high cholesterol, cancer (skin, lung, prostate, breast, colon), benign prostate enlargement, abnormal uterine bleeding, severe headaches, cataracts, HIV/AIDS and depression.

Because the CTS list of conditions is not exhaustive, the estimate of the prevalence of chronic conditions is likely somewhat conservative. In comparison, 41 percent of working-age adults reported at least one chronic condition in the 1996 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.2

Uninsured with Chronic Conditions in Worse Health

![]() onventional wisdom holds that the uninsured tend to have better

health than the insured, and CTS findings show that fewer of the uninsured reported

a chronic condition than did working-age adults with private insurance-27 percent

vs. 35 percent.3 Regardless of insurance status, people

with chronic conditions reported an average of 1.6 conditions. But, the uninsured

with chronic conditions reported much worse health and significantly more severe

physical limitations than privately insured people with chronic conditions (see

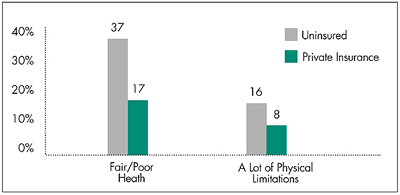

Figure 1).

onventional wisdom holds that the uninsured tend to have better

health than the insured, and CTS findings show that fewer of the uninsured reported

a chronic condition than did working-age adults with private insurance-27 percent

vs. 35 percent.3 Regardless of insurance status, people

with chronic conditions reported an average of 1.6 conditions. But, the uninsured

with chronic conditions reported much worse health and significantly more severe

physical limitations than privately insured people with chronic conditions (see

Figure 1).

Nearly 40 percent of the uninsured with chronic conditions indicated they were in fair or poor health, compared to less than 20 percent of the privately insured with chronic conditions. In addition, the uninsured were twice as likely to report having physical limitations that significantly restricted their ability to perform moderate activities such as moving a table or pushing a vacuum cleaner.

Figure 1

Health and Physical Limitations of Working-Age Adults with Chronic Conditions

Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-99

Uninsured Far Less Likely to Get Needed Care

![]() ninsured people with chronic conditions are particularly at

risk for not obtaining medical care when needed (see Table 1).

More than a quarter said they hadn’t obtained needed medical care at least once

in the past year, compared to less than 10 percent of the privately insured with

chronic conditions. And, more than half of the uninsured with chronic conditions

delayed care in the past year, while only about a quarter of those with private

insurance postponed care. This was true even after adjusting for health status.

4

ninsured people with chronic conditions are particularly at

risk for not obtaining medical care when needed (see Table 1).

More than a quarter said they hadn’t obtained needed medical care at least once

in the past year, compared to less than 10 percent of the privately insured with

chronic conditions. And, more than half of the uninsured with chronic conditions

delayed care in the past year, while only about a quarter of those with private

insurance postponed care. This was true even after adjusting for health status.

4

The negative effects of being uninsured are substantially greater for working-age adults with chronic conditions than for those without any such conditions. The uninsured with chronic conditions were 3.3 times more likely not to obtain needed medical care than the privately insured, while the uninsured without chronic conditions were 2.7 times more likely not to obtain needed care-a 20 percent differential. The differential for delaying care was even greater-more than 35 percent.

| Table 1 Level of Risk for Delaying or Not Obtaining Care (Percent of persons by chronic condition and insurance status) |

|||

| Uninsured |

Privately Insured |

Ratio: Uninsured/ Private |

|

| Did Not Obtain Needed Care | |||

| Chronic Condition(s) | 27% |

8% |

3.3 |

| No Chronic Condition | 13 |

5 |

2.7 |

| Delayed or Postponed Care | |||

| Chronic Condition(s) | 54 |

27 |

2 |

| No Chronic Condition | 28 |

19 |

1.5 |

| Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-99 | |||

Major Barrier to Care: Cost

![]() he uninsured with chronic conditions tend

to have much lower incomes, and cost is

the major barrier to care for the uninsured,

much more so than for the privately insured

with chronic conditions. Sixty-three percent

of the uninsured with chronic conditions

had family incomes of less than 200 percent

of poverty, compared to 18 percent of the

privately insured with chronic conditions.

he uninsured with chronic conditions tend

to have much lower incomes, and cost is

the major barrier to care for the uninsured,

much more so than for the privately insured

with chronic conditions. Sixty-three percent

of the uninsured with chronic conditions

had family incomes of less than 200 percent

of poverty, compared to 18 percent of the

privately insured with chronic conditions.

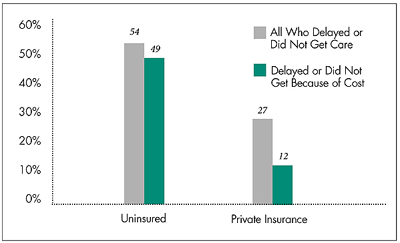

The vast majority of the uninsured with chronic conditions who delayed or did not get needed care in the previous year did so because of cost concerns (see Figure 2). In contrast, less than half of the privately insured with chronic conditions who delayed care did so because of cost issues.

Figure 2

Working-Age Adults with Chronic Conditions Who Delayed or Did Not Obtain Needed Care

Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-99

Health Care Services Received

![]() n spite of difficulties getting needed care in a timely manner,

most people with chronic illnesses do receive some care (see

Table 2). While it is unclear that all treatment received by the privately

insured with chronic conditions is appropriate and needed-or that all of the care

needed is provided or coordinated properly- it is clear that the uninsured with

chronic conditions receive significantly less medical care, even after adjustments

for health status.

n spite of difficulties getting needed care in a timely manner,

most people with chronic illnesses do receive some care (see

Table 2). While it is unclear that all treatment received by the privately

insured with chronic conditions is appropriate and needed-or that all of the care

needed is provided or coordinated properly- it is clear that the uninsured with

chronic conditions receive significantly less medical care, even after adjustments

for health status.

For example, almost 25 percent of uninsured people with chronic conditions did not see a doctor at least once in the past year, compared to less than 10 percent of the privately insured. The uninsured reported an average of four doctor visits, about 30 percent fewer than those with private insurance. While the two groups had about equal numbers of hospital admissions on average, the uninsured underwent about half the number of surgeries, even after adjusting for health status, suggesting the uninsured with chronic illnesses may receive less intensive medical intervention.

Lack of health insurance likely contributes to inappropriate use of emergency departments by people with chronic conditions, resulting in higher costs and possible capacity problems for the health care system. Compared to the privately insured, the uninsured with chronic conditions reported almost twice the number of emergency room visits.

| Table 2 Health Service Utilization by People with Chronic Conditions |

||

| Uninsured |

Privately Insured |

|

| Percent with at Least One Doctor Visit | 74 |

92 |

| Number of Doctor Visits (Mean) | 4 |

5.6 |

| Number of ER Visits (Mean) | 0.81 |

0.43 |

| Number of ER Visits Without Hospital Admission (Mean) | 0.67 |

0.35 |

| Number of Hospital Admissions, Excluding Childbirth (Mean)* | 0.18 |

0.17 |

| Number of Surgeries (Inpatient and Outpatient) (Mean) | 0.15 |

0.28 |

| * Uninsured and privately insured not significantly

different from each other. Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 1998-99 |

||

Policy Implications

![]() eople with chronic conditions are more

likely to be insured, presumably because they

value and need health insurance more than

people without ongoing health problems.

Many people with chronic conditions, however,

cannot obtain affordable coverage.

eople with chronic conditions are more

likely to be insured, presumably because they

value and need health insurance more than

people without ongoing health problems.

Many people with chronic conditions, however,

cannot obtain affordable coverage.

Overall, the uninsured with chronic conditions face more serious health problems and more barriers to needed care than insured people with chronic conditions. The long-term health implications of failing to receive preventive and ongoing medical care can be serious for people with chronic conditions. Indirect costs of chronic illness-lost workdays and sick pay-are considerable,5 and neglected care now may mean additional future productivity losses and costs to the economy.

The added costs to the health care system are both immediate and long-term. Providing nonurgent care in emergency departments is more expensive than providing care in more appropriate sites. The relatively high use of emergency departments by the uninsured with chronic conditions can contribute to hospital capacity constraints that sometimes prompt emergency departments to divert ambulances to other hospitals. Moreover, difficulties obtaining care now may result in higher long-term demand for more expensive services if the lack of treatment results in more serious health problems for those with chronic conditions.

Policy makers are debating different proposals to expand health insurance coverage, but none focuses specifically on the segment of the uninsured population with chronic conditions. Yet, because of their medical needs, people with chronic illnesses are precisely the ones who can benefit most from insurance coverage-especially if they also have low incomes.

Given the significant human and economic costs of chronic illness, policy makers should consider and assess the impact of various coverage proposals on low-income, uninsured people with chronic conditions. The bottom line: health insurance counts for this vulnerable group.

Notes

Web-Exclusive Data Tables for Issue Brief No. 49

- Health Care Delays, Health Limitations and Health Service

Utilization for Working-Age Adults with Chronic Conditions by Insurance Type,

1999

- Demographic Information for Working-Age Adults with Chronic Conditions by Insurance Type, 1999

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

Director of Public Affairs: Richard Sorian

Editor: The Stein Group

For additional copies or to be added

to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549

(for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261

(for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org