Seeking Health Care Information: Most Consumers Still on the Sidelines

Issue Brief No. 61

March 2003

Ha T. Tu, J. Lee Hargraves

![]() ontrary to popular belief that Americans avidly seek health information—especially on the Internet—a majority of Americans in 2001 sought no information

about a health concern, according to a Center for Studying Health Systems Change (HSC) study. And, instead of surfing the Internet, the 38 percent of Americans who did obtain health

information relied more often on traditional sources such as books or magazines. People living with chronic conditions were more likely to seek information, yet more than half did not.

Education is key to explaining differences among people. Those with a college degree are twice as likely to seek health information as people without a high school diploma. As consumers are

confronted with more responsibility for making trade-offs among the cost, quality and accessibility of care, credible and understandable information will be critical to empowering consumers to

take active roles in managing their care.

ontrary to popular belief that Americans avidly seek health information—especially on the Internet—a majority of Americans in 2001 sought no information

about a health concern, according to a Center for Studying Health Systems Change (HSC) study. And, instead of surfing the Internet, the 38 percent of Americans who did obtain health

information relied more often on traditional sources such as books or magazines. People living with chronic conditions were more likely to seek information, yet more than half did not.

Education is key to explaining differences among people. Those with a college degree are twice as likely to seek health information as people without a high school diploma. As consumers are

confronted with more responsibility for making trade-offs among the cost, quality and accessibility of care, credible and understandable information will be critical to empowering consumers to

take active roles in managing their care.

- Empowered Consumers in a Changing Health System

- Level of Education is Key

- Sharing Information with Doctors

- Some Consumers Harder to Reach

- Implications for Policy Makers

- Data Source

- Notes

- Supplementary Tables

Empowered Consumers in a Changing Health System

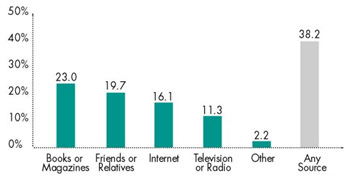

![]() ountering images of American consumers actively researching

personal health concerns, a 2001 survey of U.S. households found that only 38

percent of adults, or 72 million people, sought health information in the previous

year from a source other than their doctor (see Figure 1).

In contrast, nearly two-thirds of American adults (62%) failed to seek any health

information, suggesting significant challenges lie ahead in educating consumers

about trade-offs among the cost, quality and accessibility of care.

ountering images of American consumers actively researching

personal health concerns, a 2001 survey of U.S. households found that only 38

percent of adults, or 72 million people, sought health information in the previous

year from a source other than their doctor (see Figure 1).

In contrast, nearly two-thirds of American adults (62%) failed to seek any health

information, suggesting significant challenges lie ahead in educating consumers

about trade-offs among the cost, quality and accessibility of care.

Driven largely by concerns about rapidly rising health costs, employers are taking steps to make consumers more aware of the true costs of care.

For example, the newest product in health insurance, the consumer-driven health plan, is premised on the idea that consumers will be motivated and knowledgeable enough to shop around for the best health care at the lowest possible price. Architects of consumer-driven plans envision empowered consumers balancing the cost of care when deciding which care-giver to see or what treatment options to pursue.

Another consumer-oriented movement, patient-centered medicine, views patients as active and equal partners with caregivers in making treatment decisions. Broader-based developments affecting much larger numbers of consumers, such as increased cost sharing and tiered-provider networks—where patients must decide, for example, whether to pay more out of pocket to go to a more expensive hospital—also require consumers to be more knowledgeable.

While mainstream media portrayals of consumers actively researching health issues and discussing the information with their doctors are common, there has been little reliable national information until now about the extent to which consumers actually seek health information.1

HSC’s 2000-01 Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household Survey asked adults whether, during the past 12 months, they had looked for or obtained information about a personal health concern from a variety of sources other than their doctor, including books or magazines, television or radio, friends or relatives, and the Internet.

Only one in six consumers turned to the Internet for health information (16%, or 30 million adults). In contrast, nearly one in four adults relied on books or magazines for information (23%, or 44 million adults), and another 20 percent, or 37 million adults, turned to friends or relatives. Only a small segment of consumers is quite active in pursuing health information: About one in five adults used multiple sources to obtain health information.

Some consumers, such as the very healthy, may have no pressing need for information, and the 78 million adults living with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, asthma or heart disease,2 were more likely to seek health information. Forty-two percent of adults with one chronic condition and 45 percent with multiple conditions sought health information, compared with 35 percent of people with no chronic conditions- a surprisingly small gap (see Table 1). Nonetheless, more than half of all people with chronic conditions, or 44 million adults, sought no health information.

Figure 1

Where Consumers Seek Health Information

Note: Categories are not mutually exclusive; respondents could select multiple categories.

Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2001-01

| Table 1: Consumer’s Information Seeking and Information Sharing with Doctors1 | ||||

|

ALL ADULTS

|

ADULTS WHO SOUGHT INFORMATION AND SAW A DOCTOR MENTIONED INFORMATION TO DOCTOR |

|||

|

SOUGHT HEALTH INFORMATION ON INTERNET

|

SOUGHT HEALTH INFORMATION FROM MULTIPLE SOURCES

|

SOUGHT ANY HEALTH INFORMATION

|

||

| ALL | ||||

| CHRONIC CONDITIONS |

16.1%

|

21.2%

|

38.2%

|

23.7%

|

| NONE (R) |

14.3

|

19.1

|

34.6

|

18.4

|

| ONE |

18.7*

|

23.2*

|

42.1*

|

25.0*

|

| TWO OR MORE |

19.4*

|

25.3*

|

44.7*

|

31.0*

|

| SEX | ||||

| FEMALE (R) |

18.0

|

24.2

|

41.8

|

24.6

|

| MALE |

13.9*

|

17.7*

|

34.4*

|

21.9*

|

| AGE GROUP | ||||

| 18-34 (R) |

19.3

|

22.9

|

41.4

|

23.9

|

| 35-49 |

18.5

|

22.6

|

39.9

|

25.0

|

| 50-64 |

13.2*

|

19.3*

|

34.8*

|

25.7

|

| 65 AND OLDER |

7.7*

|

17.9*

|

33.5*

|

18.8*

|

| EDUCATION | ||||

| NO HIGH SCHOOL DIPLOMA |

4.3*

|

11.8*

|

24.8*

|

16.3*

|

| HIGH SCHOOL DIPLOMA |

10.2*

|

16.6*

|

32.8*

|

20.3*

|

| SOME COLLEGE |

18.6*

|

23.7*

|

41.3*

|

23.9*

|

| COLLEGE DIPLOMA |

24.9*

|

29.6*

|

49.3*

|

28.8

|

| GRADUATE EDUCATION (R) |

29.3

|

35.0

|

55.3

|

30.1

|

| FAMILY INCOME | ||||

| LESS THAN 200% POVERTY |

12.0*

|

18.8*

|

35.6*

|

22.9

|

| 200-399% |

15.6*

|

21.2*

|

37.8*

|

24.2

|

| 400-599% |

17.3*

|

22.3

|

40.3

|

23.4

|

| 600% OR MORE (R) |

19.0

|

22.7

|

40.3

|

24.0

|

| RACE OR/ETHNICITY | ||||

| WHITE (R) |

16.9

|

21.0

|

38.1

|

24.6

|

| AFRICAN AMERICAN |

12.2*

|

20.1

|

37.7

|

17.9*

|

| LATINO |

13.2*

|

22.4

|

39.2

|

23.7

|

| OTHER |

15.5

|

23.1

|

37.7

|

21.1

|

| 1 Table shows adjusted means derived

from a multivariate model that controls for differences in personal characteristics,

including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, income, chronic conditions,

health status and health insurance type. For unadjusted means, see Web Table

No. 1, Issue Brief No. 61, Consumers’ Information Seeking and Information

Sharing with Doctors, Unadjusted Means. * Significantly different from the reference group (R) at p<.05 level, Source HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey; 2000-01 |

||||

Back to Top

Level of Education is Key

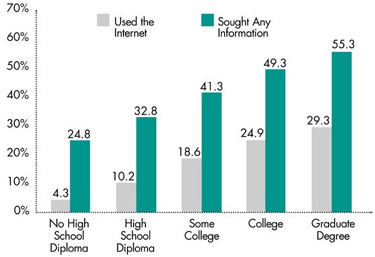

![]() mong the personal characteristics affecting whether people

are likely to seek health information, level of education is by far the most

important (see Figure 2).3

Information seeking rises sharply as the level of education increases: 55 percent

of people with a postgraduate education sought health information, compared

with only 25 percent of those without a high school diploma. The information

gap is even wider for Internet use: People with a postgraduate education are

more than seven times as likely as those without a high school diploma to use

the Internet as a resource for health information (29% vs. 4%).

mong the personal characteristics affecting whether people

are likely to seek health information, level of education is by far the most

important (see Figure 2).3

Information seeking rises sharply as the level of education increases: 55 percent

of people with a postgraduate education sought health information, compared

with only 25 percent of those without a high school diploma. The information

gap is even wider for Internet use: People with a postgraduate education are

more than seven times as likely as those without a high school diploma to use

the Internet as a resource for health information (29% vs. 4%).

Although education appears to exert the strongest influence on information-seeking behavior, other characteristics also come into play. Men are less likely than women, older consumers are less likely than younger consumers and people with low incomes are less likely than higher-income people to seek health information. All of these differences, unlike education, are modest to moderate in magnitude, with one exception: The Internet information gap between elderly Americans and younger ones is sizeable. Only 7.7 percent of people 65 and older used the Internet to find health information, compared with 19.3 percent of people aged 18 to 34.

The overall likelihood of seeking health information does not vary by race/ethnicity, once other personal characteristics are accounted for. However, minority consumers are somewhat less likely than white consumers to use the Internet as a health information source.

Passive consumers—those who seek no health information on their own—may rely on their doctors to give them all the information they need. Indeed, elderly consumers and those with less education- two of the groups least inclined to seek information actively—do tend to be more trusting of their doctors.4

Figure 2

Education Level and Information-Seeking Behavior

Note: "Any information" includes use of the Internet to find health-related information. These percentages were adjusted for other consumer characteristics shown in Table 1.

Source: HSC Community Tracking Study Household Survey, 2001-01

Back to Top

Sharing Information with Doctors

![]() mong the 72 million consumers who sought health information in the past year, only one in five mentioned the information to their doctors. Seventeen per-cent of information seekers had no

doctor visits in the past year, and the remaining 63 percent visited their doctors but did not bring up health information.

mong the 72 million consumers who sought health information in the past year, only one in five mentioned the information to their doctors. Seventeen per-cent of information seekers had no

doctor visits in the past year, and the remaining 63 percent visited their doctors but did not bring up health information.

When focusing on the smaller subset of consumers who both sought health information and saw their doctors, 24 percent mentioned the information to their doctors. Two consumer characteristics had a pronounced effect on the likelihood of sharing health information with doctors: the level of a patient’s education and the number of chronic conditions—the same factors most strongly associated with seeking health information in the first place. Among other demographic characteristics, being male, elderly and African American are all associated with a lower likelihood of raising health information with doctors.

Back to Top

Some Consumers Harder to Reach

![]() hile some consumers actively obtained health information, a majority of American adults sought no health information during the previous year. Even among people with chronic conditions, who might be expected to have the most incentive to seek health information, 56 percent sought no information.

hile some consumers actively obtained health information, a majority of American adults sought no health information during the previous year. Even among people with chronic conditions, who might be expected to have the most incentive to seek health information, 56 percent sought no information.

Some 32 million people, or 17 percent of all adults, neither sought health information nor saw a doctor in the past year. And 9 million adults had health problems—either reporting a chronic condition or fair or poor health status—yet did not see a doctor and sought no health information. Such consumers tend to have less education and lower incomes and are disproportionately uninsured, male and minority than consumers who sought information and saw a doctor. These hard-to-reach people will be at a distinct disadvantage in a health care system that demands more consumer involvement unless aggressive education strategies are targeted toward them.

Back to Top

Implications for Policy Makers

![]() ealth care information can be a double-edged sword, and much depends on the credibility and purpose of the information. Direct-to-consumer drug advertising, for example, often is cited as a factor in spiraling

pharmaceutical costs. The explosive growth of e-health as an information channel also is mentioned as a possible cause of rising consumer demand for various tests, procedures and prescriptions, which may contribute in turn to rising health care costs. Some consumers, including the so-called worried well,

may seek too much health information and spur demand inappropriately.

ealth care information can be a double-edged sword, and much depends on the credibility and purpose of the information. Direct-to-consumer drug advertising, for example, often is cited as a factor in spiraling

pharmaceutical costs. The explosive growth of e-health as an information channel also is mentioned as a possible cause of rising consumer demand for various tests, procedures and prescriptions, which may contribute in turn to rising health care costs. Some consumers, including the so-called worried well,

may seek too much health information and spur demand inappropriately.

Recent research, however, suggests that more informed patients tend to choose more conservative treatment options for certain conditions,5 so the assumption that more consumer education leads to greater demands for costly care may be invalid. To help consumers make informed decisions about the trade-offs among the cost, quality and accessibility of health care services, policy makers could take an active role in fostering development of credible and understandable information.

Consumer-centered approaches are likely to be best suited to consumers with more education who are sophisticated in seeking and using health care information. People with at least a college degree comprise only a quarter of the American adult population, so the most receptive audience for consumer-oriented strategies may be limited. But even a minority of informed and empowered consumers could spark changes in the health care system that would benefit all consumers.

Many consumer-oriented approaches, particularly consumer-driven health plans, rely heavily on Web-based tools to educate consumers.6 Yet, few consumers currently use the Internet to find health information, and Internet access and proficiency vary widely across consumers. Targeting information toward groups such as the elderly and those with less education will require providing information through multiple channels, only one component of which would be the Internet. Other special efforts, such as making complex health information accessible and understandable to diverse groups, will be needed if passive consumers are to become empowered consumers engaged in managing their own health care.

Back to Top

Data Source

![]() his Issue Brief presents findings from the HSC Community Tracking

Study Household Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey of

the civilian, noninstitutionalized population conducted in 2000-01.

Data were supplemented by in-person interviews of households without

telephones to ensure proper representation. The survey contains information

on about 60,000 people, and the response rate was 59 percent. More

detailed information on survey methodology can be found at www.hschange.org.

his Issue Brief presents findings from the HSC Community Tracking

Study Household Survey, a nationally representative telephone survey of

the civilian, noninstitutionalized population conducted in 2000-01.

Data were supplemented by in-person interviews of households without

telephones to ensure proper representation. The survey contains information

on about 60,000 people, and the response rate was 59 percent. More

detailed information on survey methodology can be found at www.hschange.org.

Back to Top

Notes

Back to Top

Supplementary Tables

Supplementary

Table 1: Consumers’ Information Seeking and Information Sharing with Doctors,

Unadjusted Means

Supplementary

Table 2: Trust, Age, Education and Seeking Health Information

Supplementary

Table 3: Latino Consumers’ Information Seeking and Information Sharing with

Doctors, Unadjusted and Adjusted Means

ISSUE BRIEFS are published by the Center for Studying Health System Change.

President: Paul B. Ginsburg

For additional copies or to be added to the mailing list, contact HSC at:

600 Maryland Avenue, SW

Suite 550

Washington, DC 20024-2512

Tel: (202) 554-7549 (for publication information)

Tel: (202) 484-5261 (for general HSC information)

Fax: (202) 484-9258

www.hschange.org